Dr. Jason Stoneback calls osseointegration (OI) a “game-changer” for amputees. He also knows that successful outcomes can’t be assumed. They have to be earned.

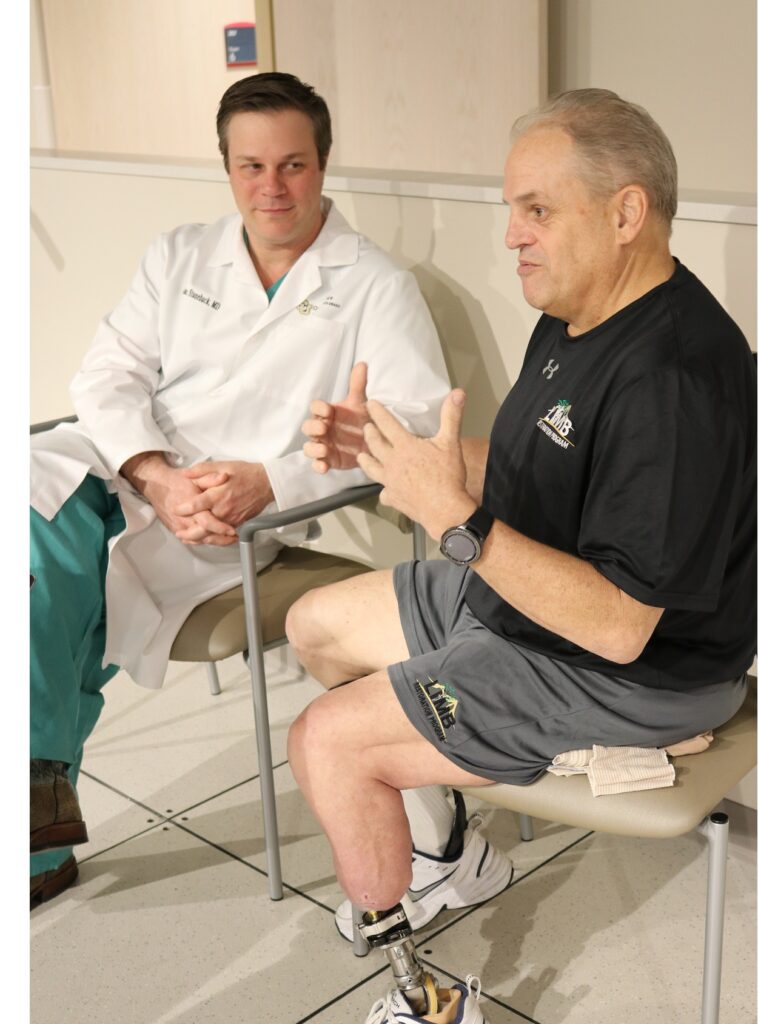

Photo courtesy University of Colorado School of Medicine.

As one of the few OI surgeons in the United States, Stoneback has seen first-hand the procedure’s potential to transform amputees’ lives. “I have a lot of patients who are very emotional because of how profound the impact is on them,” he says. Recent studies have reported sky-high success rates for OI, with major improvements in quality of life, mobility, and pain management. Our piece on Munya Mahiya from a couple of weeks ago amply illustrates the upside of OI.

Such results are incredibly rewarding to every health care professional who’s working on this breakthrough procedure. But they also may inflate expectations to a level that’s not realistic for every patient. At least, not yet.

“I think the most important thing to clarify for the amputee community is that this isn’t a cure-all,” says Stoneback, director of the Limb Restoration Program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “That’s a myth that needs to be dispelled. There are lots of factors that go into figuring out who would be a candidate for successful osseointegration. It takes an informed patient, backed by an educated team, to make the right decision.”

The exceptional success rates to date were only achieved through careful planning and detailed assessment on a case-by-case basis. Here are a few considerations that should be part of your deliberations regarding OI surgery.

1. Know your OPL from your OPRA from your ILP.

Many patients who approach Stoneback don’t fully understand the differences between the two major OI techniques. Indeed, quite a few aren’t aware that two distinct options for this type of procedure even exist.

The original form of osseointegration uses OPRA implants (short for Osseointegrated Prosthesis for the Rehabilitation of Amputees), which are screw-type devices threaded into the interior of the residual bone, similar to a dental implant procedure. A more recent category of implant, known as press fit, is impacted into the bone via a procedure that resembles joint-replacement surgery. There are multiple press fit implant systems, including ILP (Integral Leg Prosthesis) and OPL (Osseointegrated Prosthetic Limb).

“At this point we don’t know which [type of OI] is better,” says Stoneback, one of the few practitioners who performs both OPRA and press fit surgeries. “The way we handle this is to educate patients on the differences. We talk about the different connector options, the subtleties in the stoma (the opening where the implant passes through the skin), the risks of infection. It tends to come down to personal preference in a lot of cases. Ultimately we want to do the best thing for each patient.”

OPRA osseointegration has a longer track record (especially in Europe) and is offered by more U.S. facilities than press fit. It’s also the only type of OI that holds FDA approval (albeit in limited form). Press fit implants are less costly than OPRA devices, and the rehab from surgery is significantly shorter and more straightforward. But press fit OI’s availability in the United States is extremely limited. It’s not uncommon for Americans to travel all the way to Australia (home to one of the world’s leading press fit OI surgeons) to have the operation.

There are other important differences between OPRA and press fit, and Stoneback says it’s critical for patients to scrutinize them before coming to any decision. “My program feels it’s better to offer both techniques, because it’s important to me to take care of everyone and give them options,” he says. “But I want my patients to know the nuances.”

2. Get multiple perspectives, and include the home team.

“It’s really important to have a multidisciplinary evaluation,” Stoneback says—and that begins with the patient’s regular care team, including their prosthetist, physical therapist, primary care doctor, and any other health professionals who provide ongoing limb-related care. All those individuals should join the patient and the surgical team in pre- and post-operative decision-making and care.

Getting those practitioners on board at the outset pays huge dividends on the back end, Stoneback says. His own unit of orthopedists, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, rehab physicians, athletic trainers, prosthetists, plastic surgeons, and specialized nursing staff can guide patients through the operation and immediate rehabilitation. But a successful outcome ultimately requires strong partnership with the care providers who will oversee the long-range transition to routine activities.

“During the early weeks after surgery, while we’re getting the patient walking and doing well, we’re also training their home physical therapist and prosthetist so they can continue what we’re doing and anticipate some of the issues that may occur,” Stoneback says. “There’s a huge learning curve. Balancing the mechanical alignment with the patient’s body is very different than anything a prosthetist may have done before, and it has to be done well.”

As osseointegration becomes more widespread, prosthetists and other frontline care providers will gradually gain proficiency. But as of now, OI expertise is spread pretty thin within the profession. Most practitioners have rarely (or never) worked with an OI patient. Stoneback encourages amputees to bring their home team into the process on day one, so they’re well equipped to provide sustained support in the months and years after surgery.

3. Factor the most recent information into your decision.

Osseointegration is still an active medical frontier, and pioneers are constantly pushing into new territory. Some amputees who are considered good OI candidates today would have been deemed high-risk cases a few years ago. Likewise, two years from now the cost-benefit analysis will have shifted again, as better data, revised techniques, and improved hardware become available.

According to Stoneback, one key issue to watch is OI’s suitability for amputees who lost limbs because of diabetes.

“We’re actively doing research to determine which patients could safely undergo OI,” he says. “Currently, diabetes and vascular disease are seen as contraindications for OI in most cases. Poorly controlled diabetes puts you at an elevated risk of infection, and poor blood flow to a limb can affect good bone in-growth for the implant.” However, diabetes and vascular disease account for roughly half of all amputations, and patients with those conditions stand to reap enormous health benefits from the added mobility that OI affords. Because the potential gains are so great, Stoneback and other osseointegration specialists are seeking ways to lower the risks to the point that OI becomes an option for at least some patients with diabetes or vascular disease.

“My lab is looking into the patients within that population,” he says. “We have had successful OI outcomes with patients who have controlled diabetes, where it wasn’t the source of their amputation. And we’ve done people who had a vascular injury or a clot—not vascular disease, per se. So we’re looking at whether there are certain thresholds for diabetes control that can make it a reasonable risk.”

The three items above are just a few among dozens of factors every OI candidate should review with their health care team, Stoneback says. The odds of success can be affected by residual bone structure and length, muscle tone, skin condition, cardiovascular health, and many other indicators. Even successful cases may include side effects such as post-operative infection, drainage, sores, or other annoyances. Financial considerations are also critical, especially for a procedure that lacks unfettered FDA approval and therefore is difficult to code for insurance purposes.

“We want to be sure patients understand all of the tradeoffs and the risks,” Stoneback says. “Overall, osseointegration is a game-changing technique. But you have to have those conversations.”