By Emily Dings

You’ve likely experienced the trepidation that comes with making a big purchase, especially when shopping for an item you’ll use for many years, such as a car. You research features, learn the terms of warranty coverage, and read rankings and reviews. But when that item is going to become a part of your body—a prosthesis—making the right choice takes on a new level of importance.

That’s why providers like Spectrum Prosthetics & Orthotics give customers the same option available to prospective car buyers—a test drive. Some prosthetic devices cost as much as luxury car models, and if you aren’t happy with the one you’ve bought, your insurance might not cover the cost of a replacement.

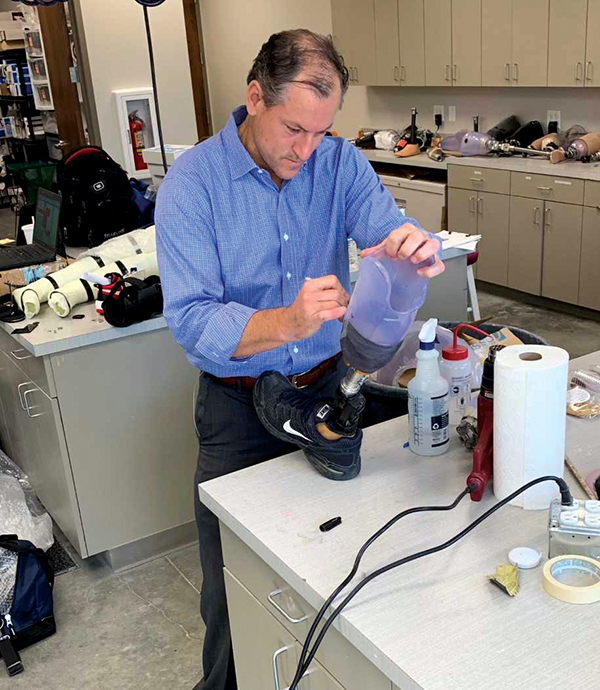

Certified prosthetist and orthotist Jeff Zeller owns Spectrum’s patient clinic in Redding, California. An amputee since 1980, he knows both personally and professionally the benefits of a trial run for a new prosthesis.

When Zeller lost his leg at age 17, there weren’t a lot of options for prosthetic devices, he says. His first device was a fiberglass exoskeletal leg with no gel liner. In contrast, for new amputees today, the vast array of possibilities—while certainly a positive development—can be overwhelming.

Amputees face a barrage of considerations about the functionality and appearance of a potential prosthesis: Would they feel comfortable wearing a device with a mechanical appearance, or would a cosmetic prosthesis feel more natural? Should an upper-limb prosthesis be body-powered or myoelectric? Should it have a voluntary opening or a voluntary closing terminal device?

A wealth of product information is now available online through social media, amputee support groups, and direct marketing from manufacturers. Consequently, customers may come to their providers with set ideas about what prosthesis they want, only to learn that it’s not actually the best choice for them.

“Because of social media, amputees are in the spotlight more,” Zeller explains. While this visibility enables amputees to have more agency over their care, being bombarded with information about advancements in prosthetics can lead to false expectations about how quickly they will be able to resume pre-surgery activities. There’s a danger in people with recent amputations wanting to go from zero to 60 with their first device. “If you danced before, there’s a good chance you’ll get to do that again,” he explains, “but you’ll have to walk first.”

A more basic device, rather than a high-end option with advanced functionality, may be the best first step on the road to a new normal. To prevent a mismatch between customer and device, Zeller emphasizes the benefits of a trial period as part of a holistic approach to care. Open, detailed communication between patient and prosthetist is key to this process.

Spectrum considers many factors, including the state of the patient’s residual limb, any anomalies, and if he or she has had other physical changes since the injury, such as weight gain or a new medication regimen. Lifestyle and goals also enter into the conversation. What is the terrain like where the customer lives? What are the patient’s daily responsibilities at work and home? What activities are they hoping to resume?

Armed with this information, the prosthetist makes a recommendation and the trial can begin. An amputee getting a prosthetic foot, for example, is fitted with a check socket, which is adjusted for comfort and stability. The client then spends a week or two testing out the prosthesis in his or her own environment, noting any hot spots or pressure points. If only minor adjustments are needed, the definitive prosthetic device is then created from the tested model. If it doesn’t work well, the prosthetist and client move on to plan B. Sometimes an alternative device may be trialed to achieve an optimum level of comfort and function.

Ultimately, Zeller says, it’s up to the manufacturer whether or not a trial period is allowed. But more manufacturers are getting on board. Trial periods typically run from two weeks to a month.

Bulow Orthotic & Prosthetic Solutions, Nashville, Tennessee, also offers clients the option to take a trial run whenever possible. Founder and certified prosthetist Matt Bulow lost a leg to cancer at age 14 and went on to become a three-time Paralympian. His own exceptional success with prosthetic devices now informs his treatment of others, which often involves testing equipment before making a purchase. “Fortunately,” he says, “we have close working relationships with the manufacturers, and they are usually able to provide us trial devices for patients as necessary.”

“In some cases, trials can be hugely beneficial,” Bulow notes. “Some patients like the clinician to use his or her experience and come up with the best solutions, but others really want to take the time and effort to personally feel the differences and benefits of devices and be more a part of the decision process.”

“My strongest advice is to communicate with your prosthetist/orthotist,” Bulow says, echoing Zeller’s counsel. “Most P&O clinicians got into the profession to help people, so communicate your concerns. If you are the type who wants to be an active participant in component selection, speak up and ask.” And while you’re at it, ask if you can try a product out before you buy it.