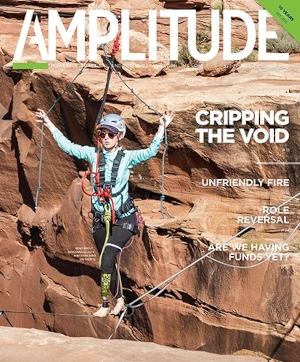

I taught myself to slackline on a prosthesis. But I needed a community to reap the rewards.

by Breeanna Elliott

Photography by Enzo Montalbano

One morning this past April, I woke up caught in the churning undertow of persistent grief. But unlike the countless preceding mornings, I felt the unusual urge to do something about it. I decided to call Faith Dickey, a world-renowned professional highliner in Moab, Utah.

The only thing I knew about Faith at the time was that she owns and operates Elevate Outdoors, the nation’s first and only guided highlining business—and I was desperate to try the sport. I was unaware that she was one of the first professional highliners and the first woman to have crossed the 100-meter length mark on a highline. She is the kind of athlete who novices and pros alike dream to one day meet, and here I was, a mostly self-taught, prosthesis-wielding amateur slackliner, calling her out of the blue. But such acts are less about overcoming the fear of failure and more about believing in unexpected possibilities. I made the leap.

Faith is usually out guiding in the mornings. But on this day, she picked up on the second ring. Kismet.

Searching for Access Intimacy

Highlining is the more extreme version of slacklining, which is similar to tightrope walking. You walk (or scoot, or however you see fit to move) along a flat webbing, one to two inches wide, that is tensioned between two anchor points (trees, rocks, etc.). When done more than a few meters above the ground, the slackline becomes a highline, the slackliner a highliner. Elite highliners like Faith traverse the open sky between deep canyons, urban buildings, and sometimes even hot air balloons. But whether you are slacklining or highlining, the challenge is fundamentally the same: to balance your way across the line.

As with most good things in life, though, the objective is not simply to cross as quickly as possible (though there are competitions for that). Slacklining at its core is about the journey across, which begins before you ever step on the line and persists long after the equipment is packed away. Though you are alone on the line, experimenting with your movement and balance, working toward a meditative focus to bring awareness to all parts of your body at once, slacklining is best done—and perhaps, can only really be fully experienced—in community.

As a below-knee amputee born with fibular hemimelia, I was searching for a disabled slacklining community after first learning from nondisabled friends. For most of my life, I have confronted the same isolating approaches even from well-meaning nondisabled others: invasive, superficial curiosity; unfounded and patronizingly low expectations; overblown plaudits for mundane accomplishments; and/or complete disregard for the fact that I am disabled and have access needs. My initial experiences with slacklining were similar. My informal instructor had such low expectations of amputees that he praised my ability to walk over uneven ground or jump across puddles. His lack of awareness made him ill-equipped to coach me through slacklining challenges related to my disability. After two amputations of my left foot and two left-knee surgeries in my teens, I had become almost entirely reliant on my right leg for balance. I could not feel whether my prosthetic leg was centered on the line—frequently, it wasn’t—and I couldn’t keep my knees properly bent in the standard slacklining posture. I couldn’t mount the line when sitting and keep my center of gravity low. I couldn’t mimic the form of nondisabled slackliners, and so far, they couldn’t help me adapt conventional lessons to my not-so-conventional body.

Worst of all, I could find no online resources or videos about adaptive slacklining. Did disabled people just not slackline? Impossible. But if any did, I couldn’t find them. So I took matters into my own hands. I bought my own equipment so I could practice alone, without unwanted attention, and figure things out through trial and error. Over time I discovered what worked for my body, building self- confidence and strength in the process. I surprised myself by accomplishing things I was previously adamant I could not do—such as balancing on my left leg, which I achieved with the help of strengthened hip and thigh muscles. Concurrently, I learned which moves my body was structurally incapable of. I could not mount the line with my left leg; I could not smoothly transfer my weight from one foot to the other. But I progressed, not discouraged by what I failed to do, but overjoyed at the experience of trying without anyone’s expectations (including my own) holding me back.

After a year of practice, I was slacklining with confidence. But I was still isolated. I longed for what disabled writer and activist Mia Mingus terms access intimacy, “that elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else ‘gets’ your access needs.” I wanted to creatively experiment with adaptive approaches to slacklining alongside other disabled people, to struggle and feel frustrated, to triumph and feel empowered, all without being perceived as “inspirational” or managing someone else’s ill-informed perception of my limitations.

Above all, I wanted to share the personal sense of renewal I had found in slacklining. Recently, I lost my older brother unexpectedly, experienced devastating heartbreak, and received a difficult medical diagnosis. I was only half alive even on the best of days. But slacklining facilitated an internal awakening and a re-tuning of my relationship with my body. It requires concentrated focus, physical and emotional presence, and a degree of mind-body alignment alien to me as a lifelong amputee and as someone ensnared in bone-deep depression. As I got better at slacklining, my overall level of self-awareness increased, improving even my ability to problem-solve socket-fit issues with my prosthetist. I got back into the habit of adapting activities to my needs, not the other way around. I was eager to share this transformative experience and take my interest in it to new and higher heights. But I could not do it on my own.

All In and Full of Stoke

Elevate Outdoors is known for its Skywalk, an elaborate top-rope highline setup at the world-renowned Fruit Bowl Highline Area just outside Moab. Highliners around the globe dream of venturing to this stunning location, which is located just outside Canyonlands National Park and belongs to the same landscape of dizzyingly steep cliffs, mesas, and chasms.

Faith developed the Skywalk so that anyone—even someone with zero slacklining experience—can try highlining safely. She frames it as “useful training wheels…more than just a shortcut, but rather a steppingstone for building highline skills.” Unlike a standard highline setup, the Skywalk is paired with an overhead line that provides additional security and a knotted handline that helps new highliners maintain balance. Faith is committed to expanding access to highlining, especially for people with disabilities, and so when I explained that I had never highlined and was an amputee, she was all in and full of stoke.

We began discussing logistics. I already had plans to be in Utah in early June, but a one-on-one, day-long Skywalk experience would be prohibitively expensive. She offered to put out a call for others who might be interested in joining, which would lower the price significantly, but there was no guarantee they would be disabled. I understood, but I repeated my enthusiasm at the prospect of learning alongside a whole group of disabled individuals. That is what I had been missing from the beginning, I told her. I wanted—but really, at this point, I needed—that disability camaraderie to keep moving forward.

We planned to touch base in a week or two, but just two hours later, she texted me with an improbable message: “I’ve got some exciting news. A person from the disability community is interested in sponsoring the Skywalk for you and a few others.”

Shortly after speaking with Faith, I connected with Ryan Juguan. In contrast to me, Ryan is a seasoned adaptive sports enthusiast and athlete: He played wheelchair basketball in college, is now a member of the national paraclimbing team, and has taught adaptive slacklining at the annual Adaptive Climbers Festival in Kentucky’s Red River Gorge. After collaborating with Elevate Outdoors and Faith last fall, he also became likely the first person with osteogenesis imperfecta (brittle bone disease) to cross a highline.

Ryan and I shared our frustrations with finding experienced slackliners and highliners who understood disability and adaptive sports. We also commiserated over the physical inaccessibility of many slacklining and highlining locations. We agreed that more disabled people should be exposed to slacklining and highlining and learn about its wide-ranging physical and mental benefits. Toward that end, we decided to create a resource to increase the visibility of disabled slackliners and provide the information, mentorship, and encouragement both of us had lacked.

This spring we founded the Adaptive Slacklining Association. Our first project would be to recruit other disabled individuals to join us at the Skywalk for the first Adaptive Highlining Day.

Stepping Together Into Thin Air

While Faith and the generous anonymous donor provided the context for all of us to meet, it was Ryan who brought us together as a community. We were an eclectic, differently disabled group of five: Dan, Ginger, Josh, Ryan, and me. Dan, who like Ryan is on the national paraclimbing team, is a recent above-knee amputee who had never highlined and had not slacklined since his amputation. Josh, an experienced rock climber who has a spinal cord injury, had attended Ryan’s adaptive slacklining workshop at the Adaptive Climbers Festival last year, but he hadn’t been on a line since then. Ginger had never slacklined. All of us, except for Ryan, were entering uncharted territory.

The afternoon before our Skywalk experience, Ryan invited us to gather at Moab’s Swanny City Park, where we established an informal clinic. Ryan taught us how to set up a primitive slackline (a slackline tensioned sans rachet), which we did while falling over each other and trying to avoid the very active ant community next to one of our anchor trees. At first, we were all reluctant to get on the line, uncertain of how we would perform in front of each other, but Ryan’s encouragement was infectious. He challenged us to experiment before drawing conclusions about what we could and couldn’t do. Our makeshift clinic lasted well into the evening, creating exactly the kind of access intimacy that Mingus writes about. She describes it as “ground-level, with no need for explanation” and no need “to justify.” It is an intimacy shared with those “who have an automatic understanding of access needs out of our shared similar lived experience of the many different ways ableism manifests in our lives.”

By sunset, we were all attempting Ryan’s signature move, which we dubbed “the Juguan,” a wildly challenging full-body scoot. Reveling in our shared access intimacy, we interspersed slacklining tips with discussions about dating when disabled—do you include your wheelchair in an app photo, or not?—and lessons on how to properly don a climbing harness without looking like a fool.

It was the first time I had experienced the enlivening joy of being in a disabled community this way, outside of a medical clinic, hospital, or advocacy meeting. We were just people being together, exploring different movements with our bodies, and getting stoked. If the trip had ended there and I had never even seen the highline, it would have been worth it all.

Early the next morning, we reconvened at the Fruit Bowl, peering into the famous 350-foot depths of Mineral Canyon. We were mainly there to have fun together, but in the process, we were also “cripping” highlining—normalizing disabled participation while actively reimagining what the sport is, who it’s for, and how it’s done.

I was the first to step on the highline that hot summer day, but it felt like we all did it together. I borrowed Dan’s hex key to tighten my foot (the convenience of being around other amputees!) while Faith and her assistant, Brian, went through all the safety checks with me. Josh and Ryan directed me how to properly put on the full-body harness, while Ginger, a multi-talented Moab artist with multiple invisible disabilities, began capturing the scene on camera.

After the last-minute addition of some rope and tape to ensure my prosthesis wouldn’t join the forgotten hats, sunglasses, and other items that have fallen to the bottom of the canyon, Faith walked me over to the Skywalk and tied me into all the lines.

It was the first time I had gotten close enough to the cliff’s edge to appreciate the Fruit Bowl’s depth. Highliners often speak about the full-body fear they face when they step on the line, even when they are safely secured to it. I anticipated that I, too, might feel that fear when finally confronted with the 350-foot chasm. But I did not. I felt only supreme joy as I took my first step off the cliff while the group, huddled under the only shade tree in that corner of the Utah desert, cheered me on.

Each of us experienced Adaptive Highlining Day differently, because we each carry our own distinct and ever-evolving relationship with our bodies and our disabilities. Some of us were frightened; some of us thought we couldn’t do it; some of us already knew we could; some of us needed to prove something to ourselves; some of us had nothing to prove. Disability and the state of being disabled are dynamic categories, impossible to pin down, and the effort to do so universally is ultimately a disservice to us all.

As the afternoon started easing toward evening, and we began feeling the parts of our skin the desert sun had kissed too greedily, we journeyed back toward the gravel parking lot, away from the tantalizingly colorful red rocks of the canyon. I noticed tender bruises forming on my inner thighs and forearms from the day’s exertions, and we all cursed the trail back. As we moved together, the late Andrea Gibson’s poem “Tincture” wound its way through my mind:

Imagine, when a human dies,

the soul misses the body, actually grieves

the loss of its hands and all

they could hold…The soul misses the lisp,

the stutter, the limp. The soul misses the holy bruise

blue from that army of blood rushing to the wound’s side.

On that day, I could imagine just how much my departing soul will miss the particulars of my disabled body—my creaking, clacking, and clicking. Look not at what it can no longer do. Look at all that it does.

For Every Kind of Explorer

While we all felt far more than good that weekend, this is not a feel-good story. None of us overcame adversity. What we overcame—or more accurately, struggled through together—was inaccessibility. Getting to the highline was harder than getting on the highline in most respects. The trail to the Fruit Bowl is quite uneven, requiring light scrambling here and there, navigating occasional sandy surfaces, and working one’s way across and between rocks and boulders. For Ryan, a wheelchair user; Josh, who alternates between a wheelchair and forearm crutches; and Dan, who was using crutches prior to receiving his new prosthesis, the trail to the highline and back was the greatest physical challenge of the day. But what about those who could, can, and want to highline, or engage in other extreme sports, but cannot do so only because the literal and figurative path to the starting line has already precluded their participation? If Moab really aims to be “for every kind of explorer,” as its signs claim—and if the International Slackline Association aims to promote slacklining in all forms—we need to acknowledge the dearth of adaptive opportunities and lack of basic trail accessibility. We need to see change.

Faith and Elevate Outdoors are working to make extreme sports and the outdoors more accessible, and so are we at the Adaptive Slacklining Association. This story is only the beginning; it is a call to action in many ways, but most importantly, it is a call to community. Come as you are. Join us!

For more information about the Adaptive Slacklining Association, visit adaptiveslacklining.org.