By Elizabeth Bokfi

My back is screaming in protest. I’m ingesting copious amounts of ibuprofen and beginning to consider the little orange pills, in the little orange bottle, in the drawer that hasn’t been opened in years. I’m wearing a prosthetic socket that hasn’t been right for quite some time, and standing for more than a minute is excruciatingly painful. I haven’t been nearly as mobile as I usually am. And guess what? My outlook is pretty crappy as a result.

Why do we put off going to the prosthetist for corrections to our prostheses? Is it cost? Is it embarrassing to request something so vital to our physical and emotional well-being? Do we feel like we’re inconveniencing our prosthetist?

I finally resort to stepping into my swim leg—an old prosthesis with a worn-out adjustable-heel-height foot. It’s reasonably comfortable, provided I don a thick, ugly, 5-ply woolie. At this point, desperation trumps esthetics. Lo and behold, even though the foot is ratcheting and creaking like an engine about to blow up, my back pain seems to dissipate after a couple of hours and I can make it through a grocery shopping session—for now.

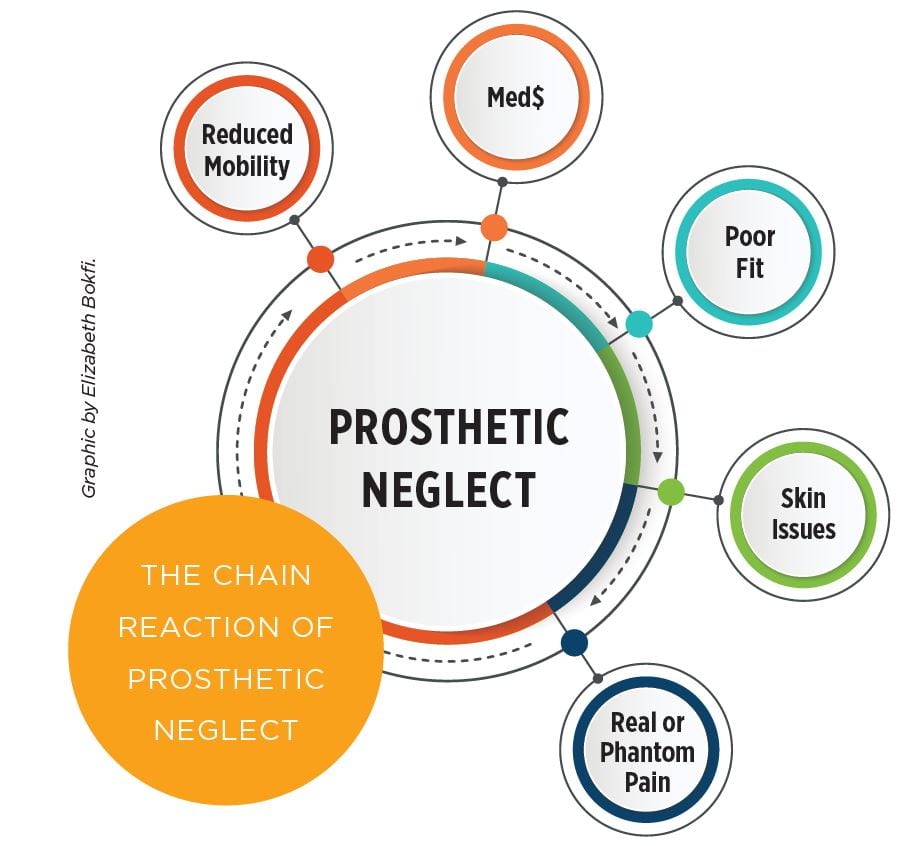

It’s the chain links that get us. Every action or inaction has a reaction when it comes to prostheses, their fit, and the impact their good (or poor) maintenance has on our activities of daily living. Taking good care of our prosthesis is an important link in preventing a chain of negative outcomes, such as poor fit, skin issues, pain, reduced mobility, and the need for medication.

Equally as important as maintenance is having a prosthesis that is geared toward the level and type of activity an amputee experiences daily. Using activity-appropriate components can prevent prosthetic failure and potential falls and injuries.

On July 20, 1992, retired Staff Sgt. Larry Corley, from Columbus, Ohio, suffered a shattered right leg when a rappelling mission with his special reconnaissance operations team went wrong. Hanging from a Black Hawk helicopter, Corley hit the ground after falling from 80 feet in the air. In and out of Womack Army Medical Center, he endured 15 surgeries that first year while continuing to train troops.

Dealing with severe nerve damage and the resulting pain, Corley continued to trudge through duties for the next seven years before pain management efforts began to fall short of actually managing his pain. He began considering amputation. After careful consideration, on July 20, 1999, seven years to the day after his accident, Corley’s right leg was amputated below the knee, using the Ertl procedure.

Once healed, Corley began working with the prosthetics team at WillowWood as an educational specialist, which gave him plenty of opportunities to test many prostheses.

Fully retired now and with 18 years of amputee experience under his belt, Corley understands the importance of knowing how to care for his residual limb, prosthetic maintenance, and having the appropriate prosthetic foot geared to his type and level of activity.

He currently wears a Pathfinder™ II foot, which offers him more stability and helps him maintain a high level of activity, while reducing the risk of fall and injury, which can be costly. “It’s a very hard-core foot with lots of energy return and will tolerate heavy use,” says Corley.

Taking proper care of your prosthesis also means being able to recognize when something’s wrong—a result of knowing your body, knowing your equipment, and having a good working relationship with your prosthetist. Feeling comfortable speaking candidly about your prosthetic needs and going to the clinic right away when an issue crops up can head off trouble. You may feel like you’re being picky when you explain the issues happening with your prosthesis, but the reality is, if they are not corrected, they can cost you a lot of time and money. It’s easy to see how components that are broken or have deteriorated can create a chain reaction: Broken component > shift in weight/gait > back pain > phantom limb pain > residual limb issues > pain management > time off work.

“One thing I have noticed during my years of traveling, prosthetists want to adjust these ‘high speed’ feet the same as a SACH [solid ankle, cushion heel] foot,” says Corley. “That reasoning doesn’t help amputees. We are wearing ‘concrete’ feet and quickly lose motivation with this insensitive attitude…. Finding a prosthetist that fits is the most important in my opinion. Does he/she pay attention? Understand us and our attitude [toward] living our lives?”

Wearing the correct prosthesis for your activity level can enhance mobility—with the result being an overall higher sense of satisfaction with quality of life; however, maintenance is an important part of the recipe.

Jim Low, BSc, CP(c), of Prosthetics Orthotics Barrie, Ontario, Canada, says socket fit is one of the most important things to consider when it comes to an amputee’s satisfaction with his or her quality of life. “Socket fit dictates so much in an amputee’s life,” says Low. “If the socket fit isn’t right, not much else is right in life. We have available all sorts of fancy ankles, feet, to go with the socket, but if the socket isn’t right, it doesn’t matter how expensive the foot is—the leg doesn’t work right. It all starts with the socket.”

A well-functioning prosthesis can be life-changing when it enhances mobility, and although part of a prosthetist’s job is to help you maintain or achieve mobility through a properly maintained and functioning prosthesis, it can’t all fall on the prosthetist’s shoulders. Patients bear a certain responsibility in keeping themselves mobile and ultimately having higher satisfaction with their quality of life. Low has seen his share of neglect on the patient’s part in caring for themselves and their prosthesis.

“We have people that just don’t look after their skin,” says Low. “They don’t look after their device; they don’t keep it clean. Their socks and silicone gel liners need to be looked after properly, and when they don’t, they get hygiene problems, which can lead to rashes, skin breakdown, and can be a real mess.”

Low has also seen patients trying to save money by not tending to issues with their device. “What starts off as a minor issue doesn’t get dealt with,” says Low. “They don’t want to come and get it looked after. It may be money, or maybe they just don’t have time, and then that little problem escalates and then it becomes a major issue and they end up being off their leg until things heal.”

If it comes down to money, or rather the lack of it, Low suggests his top three priorities when it comes to maintenance:

- Volume correction.

Add pads to a socket [to take up space]; acquire socks of varying thickness. - Alignment changes.

Make sure the position

of the socket is relative to other components of the artificial limb. - Length adjustment. Ensure the height of the prosthetic pylon is appropriate to the opposite leg.

And what about my back pain that was caused by problems with my prosthesis? Fortunately, it’s gone now. It’s amazing what an intact prosthetic component (as opposed to one that has a San Andreas fault line running down the side of it) means to one’s back health and not falling off the gym’s elliptical machine. Perhaps getting a maintenance check sooner would have been to my benefit.

Every action or inaction has a reaction when it comes to prostheses, their fit, and the impact their good (or poor) maintenance has on our activities of daily living.