After a career as an award-winning animator, Paul Demeyer is documenting his limb-loss journey in paper and ink.

As Paul Demeyer was recovering from his second below-knee amputation, everyone on his care team was full of encouragement.

“They’d say, ‘A year from now, you’ll be running a marathon,’” Demeyer recalls. “And I thought: I never wanted to run a marathon when I was younger and had both legs. Why would I want to run one now?”

In a sense, Demeyer—who was then in his late 60s—had been running a marathon for decades. Diagnosed with type 1 diabetes as a child, he nearly lost his eyesight in his late 30s, threatening to end his career as an illustrator. Doctors preserved enough of Demeyer’s vision to save his career; he went on to garner awards for his work in TV and film animation, most notably on the iconic Rugrats franchise.

When he lost his legs a few years ago, also as a result of diabetes, Demeyer was close to retirement and had decades of professional success to look back on. But the transition was still jarring, because it came at a stage of life that’s inherently freighted with loss—of physical capacity, familiar routines, friends and loved ones, and other central aspects of self.

“When you’re 60 or 70, your body doesn’t have that extra push [to recover] that it had at 30,” he observes. But the corollary is that our minds at age 30 don’t have the same depth of perspective that they’ve acquired by age 60 or 70. “If this had happened to me when I was 30, I think I might have been more devastated by it,” Demeyer says.

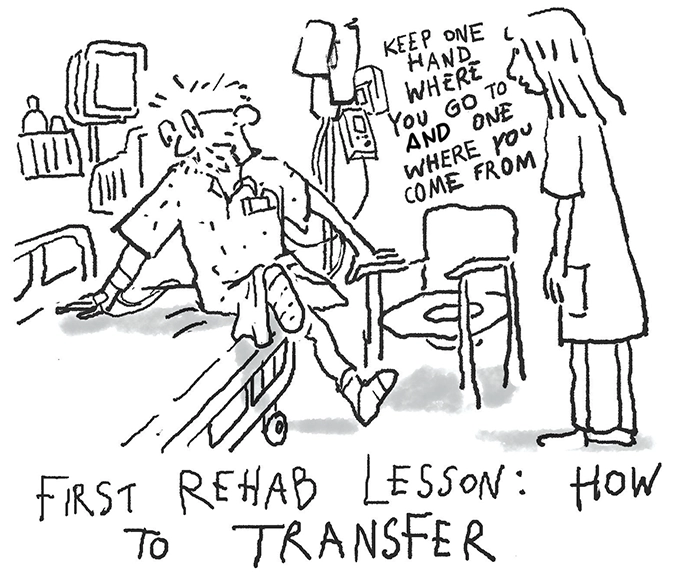

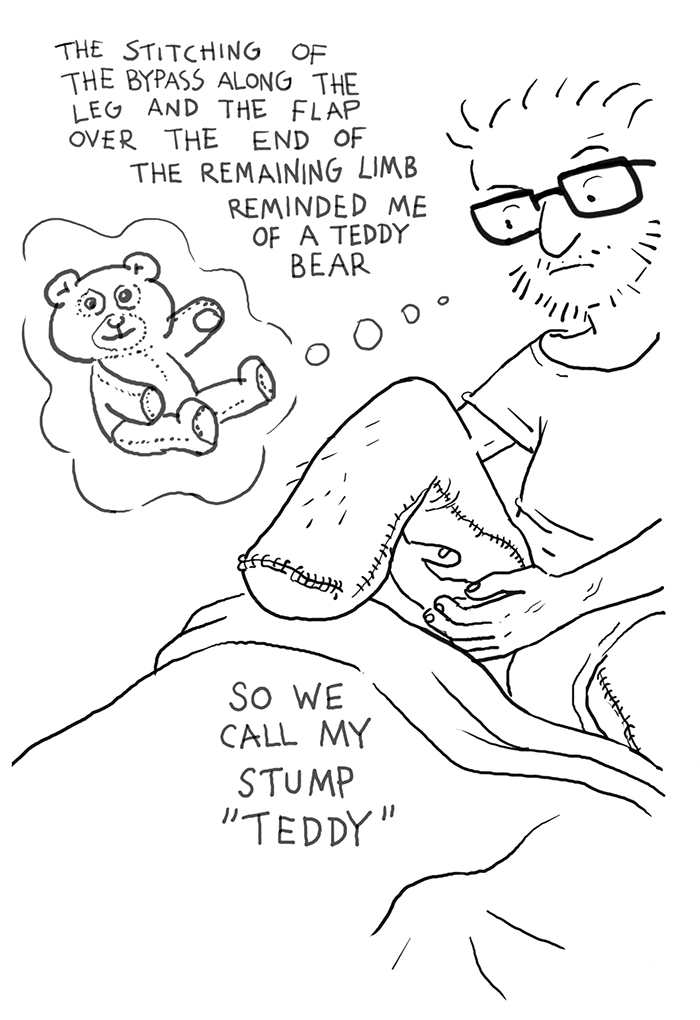

Which is not to say that limb loss has been easy. Like everyone, Demeyer battles through ups and downs. When he got home from the hospital, he started processing his emotions in paper and ink, and while the artwork wasn’t polished, it did tell a story—not just a personal story, but a broadly relatable one about accepting change and finding purpose and renewal within it.

“That’s when I thought, ‘Hang on a minute. This could be a book,’” Demeyer says. And so it shall be. He’s close to finishing an illustrated memoir that documents his adaptations to disability and his ongoing search to find peace, balance, and spiritual meaning.

Demeyer, who lives in Los Angeles, spoke with Amplitude earlier this year about his forthcoming book and his experience with limb loss. He also was generous enough to give us a sneak preview of some rough drawings from the book—works in progress, not final products.

To learn more about Demeyer’s career as an animator and to keep tabs on the book’s status, visit pauldemeyer.com. The conversation is edited for clarity and length.

Tell me about the genesis of the book.

I’m not the kind of guy to tell my story to a lot of people, but somehow I had to work through this experience. So many, many things went through my mind. And drawing has always been a very therapeutic tool of expression for me, even as a child. That’s all therapy is, really. It’s about expressing what you’ve gone through and unloading it.

When I got home from the hospital, I started doing this sketchbook to work through everything that had happened. These were really quick sketches, not great drawings. I was just unburdening myself. But I knew there are a lot of people who might relate to them. Not just amputees, but also their family members. And not just people who have amputations, but anyone who has to get through some difficulties in their life.

I have the impression the book goes into more than your limb loss.

That’s where it started. But when I started putting everything together, I realized there’s more to my life than amputation and diabetes, so it kept getting bigger and bigger. For a while I thought about doing separate volumes about my career, my diabetes, my amputations, and my spiritual search. But that’s not really true to the situation. Life is not as delineated as we want it to be.

How did amputation become necessary for you?

I was 64 when I started to get the symptoms that led to amputation. I had the angioplasties and the bypasses to the feet and all that. And there was the pain, the incredible pain. My doctors told me I would eventually give up my feet either because of the pain or because of an infection. I asked, “Can we do a last angioplasty?” So they did, and they said afterward that even though it didn’t save the foot, at least they were able to amputate below the knee.

Did your experience with vision loss help you adapt to losing your legs?

When I lost my eyesight, it came from left field. I didn’t want to face the reality of what it means to have diabetes, and I did not think [vision loss] was ever going to happen to me. I went to different doctors and tried different things. I had a lot of operations, but it was not making things better.

I went back to Belgium, where I’m from, and someone told me I should see an eye doctor in Antwerp who was doing vitrectomies. This was very new at the time. Hardly anyone was doing it then; now it’s very common. And they were able to save some vision in my right eye—about 20/50 vision, very narrow.

After the last operation, I remember going into my dad’s office and starting to draw. I couldn’t do fine drawing anymore, like I could do before, but I could still draw. And a blanket of peace kind of fell over me. As long as I could do that, I knew it was going to be okay. I bought a little monocular that enlarges things, and by looking through that, I could actually see something in a shop window, or I could see the number of the bus that was coming. Little things like that can be so simple, yet so important.

Did you have a similar moment after your limb loss, where you thought to yourself: It’s going to be okay?

I did have a moment like that. My wife and I went to a mobility exhibition at the convention center, and seeing the children with lost limbs made a big impression. They were totally involved in play, totally involved with life. Missing a limb is what they know. When you get involved like that—when you give yourself to it—then you’re living. Seeing that was an inspiration to me.

Another moment was the first time I went back to the studio after my amputations. There were about 100 people working there at the time, and everybody came to the conference room. That was so touching to me. I felt so much love, so much compassion.

Tell me about the spiritual search that’s a part of the book, and part of your life.

When I was 23, I started to do transcendental meditation. At first I was very naive; I thought I was on my way to be enlightened or something. But I was still very much in the grasp of my emotions. It wasn’t until I was in my 30s that I met a teacher who taught me to live in the present moment and face emotions for what they are—to be true about whatever is happening in your life and really face whatever you’re facing.

By the time I had the amputations, that idea was already very strong in me. And it can be hard, when you’re in pain, to find that sensation of stillness and well-being. The pain in my feet and my legs was just excruciating. But there is something about acknowledging when things are good and there is no pain. I’m just now looking outside, and I see a tree just outside the window with the wind in the branches and the leaves, and the light is reflecting and it’s extraordinarily beautiful. Just to acknowledge that in your everyday life, rather than focusing on the difficulties, is a challenge.

Then in my 50s, I started to go back to church. I never thought I would, because I had such opinions about organized religion. But I started to come to this realization that I had been rejecting it most of my life. There’s this beautiful poem by St. John of the Cross—he’s one of those Catholic mystics from the 1500s, and he had this vision of people crossing a river toward the kingdom of God. The name of the river was Suffering, and the name of the boat was Love. To me, that encompasses everything. Because we all suffer. Someone loses his wife or his child or a limb or a job, whatever it is. There are enough ways to be unhappy, right? But it is love that carries us.