By Larry Borowsky

“Will I still be able to surf?”

That’s the first thing Albert Lin asked his physician after a Jeep rollover crushed his right leg in 2016. Not “Will I be able to resume my career as a telegenic, globe-trotting scientific investigator?” Nothing about galloping across Asian steppes or trekking through Central American jungles. Nary a word about Lin’s day job as a research professor at the University of California San Diego.

Such considerations were secondary at that moment. For Lin, a San Diego native and longtime surfer, the paramount concerns were the beach and his board. Just tell me I can still ride, doc. Just give me that, and I’ll figure out how to deal with the rest of it.

The doctor dodged the question and changed the subject. Not a good sign.

The answer hung in suspense for several weeks as Lin investigated various treatments that might salvage his limb. The medical pros never did offer a definitive opinion about surfing, but Lin got clarity from some strangers who visited him in the hospital.

“My doctor invited one of his former patients to come see me,” he recalls, “and this guy walks in carrying a bag full of legs. He had shorts on, and I don’t think I would have noticed he was an amputee without that. I didn’t notice any limp. That was probably the first time I ever saw an amputee walking in real life.”

The man was an active horseman, which impressed Lin—he’d just spent several months riding horses across Mongolia while shooting a documentary for the National Geographic Channel. A few days later, a second below-knee amputee walked in and introduced himself to Lin. “He’s got this ultramarathon body,” Lin remembers. “I mean, he was fit. He’s got all these high-tech legs, like he’s MacGyver or something. And as it turned out, he surfed every day.”

The clincher came when international parasurfing champion Mike Coots reached Lin by phone and offered words of encouragement. Coots said he was headed to San Diego in a few weeks for a Challenged Athletes Foundation fundraiser, and he hoped Lin could get out of the hospital in time for a face-to-face meeting. “By that point, I had made my decision [to amputate],” he says. “I think my friends and my family had trouble accepting the idea. But I was ready to move on.”

A week after the operation, Lin made it to the Challenged Athletes event. There, right in his hometown, he got introduced to a community and a culture as remarkable as any he’d encountered in his travels to remote regions on faraway continents.

“I saw all these incredibly empowered people cheering each other on,” he says. “I saw this entire world of people who were just driven by a positive mental attitude. That was my first week of being an amputee. You couldn’t ask for better timing.”

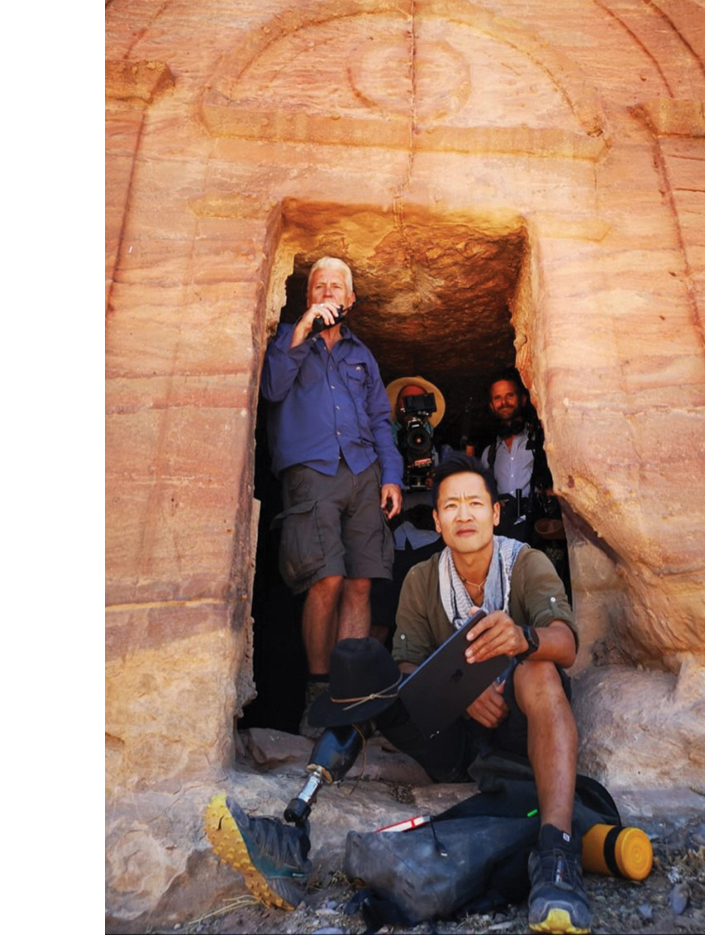

FOUR YEARS LATER, LIN HAS INDEED RETURNED TO SURFING, horseback riding, trekking, climbing, and all the other outdoor passions he’s pursued all his life. He’s resumed his boundary-pushing pursuit for knowledge and truth, hosting two series for National Geographic (Lost Treasures of the Maya and Lost Cities with Albert Lin) since his amputation. So far this year he’s journeyed to Africa and Central America for a new film project that he can’t discuss in detail yet.

Neither Lin’s identity as a world-class adventurer nor the galactic scope of his activities has been diminished by limb loss. You could argue the experience hasn’t changed him at all. But you’d be wrong. Lin now understands how it feels to be unable to carry a glass of water from the tap to the kitchen table. He’s been stopped in his tracks by phantom limb pain. Yes, he’s still crisscrossing the globe with the dash and panache of Indiana Jones. But everywhere he goes, he sees people he might have overlooked before—people who remind him that nobody should ever take their mobility for granted.

“On one of my first trips out [after limb loss],” he says, “I saw this guy on a beach, an amputee, who was walking around on crutches while I’m standing there with a carbon fiber leg. It just didn’t feel fair to me. He started playing soccer with his friends, still on his crutches. I felt almost embarrassed of my privilege at that point.”

Lin thought back to the amputees who had visited him in the hospital and helped him embrace the decision to amputate. He recalled how the Challenged Athletes Foundation experience made such a powerful, positive impression on him as a new amputee. And he started thinking about how he could make a difference in people’s lives—to serve not just as symbol of amputee empowerment, but as an active agent of it.

One day in India, Lin came across a farmer who was wearing a prosthetic leg. “He was working his fields out in the middle of nowhere,” he recalls. “And we had this whole experience together. We got to share our joy of our reclaimed mobility.” Lin found out the farmer had received the prosthesis from Jaipur Foot, the world’s largest nonprofit support organization for people with disabilities. Since 1975, Jaipur Foot has distributed millions of prosthetic devices and other mobility aids to amputees in India and roughly 30 other countries. But despite such heroic efforts, about 95 percent of the world’s amputees lack access to a prosthesis for two key reasons: the global shortage of qualified prosthetists (especially in developing countries) and the high cost of prosthetic devices.

That awareness spurred Lin into action. In 2019 he established Project Lim[b]itless, an ambitious initiative to broaden access to prosthetic devices using digital technology. Based at his UC San Diego lab and funded by the Qualcomm Institute, Project Lim[b]itless reflects Lin’s global outlook and big-picture thinking. Its key feature is a smartphone-based interface that enables an amputee to create a minutely detailed 3D model of their residual limb and transmit it to a prosthetist anywhere in the world. The prosthetist, in turn, uses the 3D scan to custom-build a tight-fitting socket that can restore the individual’s mobility. In theory, this model could enable almost every amputee—even those living in the isolated locales Lin explores on his TV shows—to connect with a prosthetist who has the training and skill necessary to provide high-level care.

“Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what gear you have beneath you,” Lin says. “The thing that really matters is the fit of the socket. You have to shape something that fits you so well that it allows the most wounded part of your body to carry the load of your entire body. There is this deep artistry associated with getting the fit exactly right. A few millimeters in certain areas of your socket will make the difference between you being able to do everything you want to do, or not.”

LAST FALL, LIN JOINED THE BOARD of another large-scale amputee-support project based in San Diego. Called the Right to Walk Foundation, the new organization is geared specifically toward American amputees who aren’t getting the care they need to reclaim their lives fully after limb loss.

“A lot of amputees are living a life where they can hardly walk around,” says Shellie Plasch, the Right to Walk Foundation’s executive director. “In many cases, they don’t know how to advocate effectively for themselves. We want to help people get back to their lives, be productive, and avoid the problems that happen when you don’t have adequate prosthetic care. Every amputee has the right to something that really works for them.”

Like Project Lim[b]itless, Right to Walk seeks to broaden access to prosthetic care via a whole-system approach. In addition to helping individuals afford prosthetic devices, the organization will address stingy insurance, poor socket performance, gaps in consumer awareness, and other issues that often leave amputees frustrated to the point of despair.

“I’ve seen people who’ve lost their confidence and don’t think they can do all the things they used to be able to do,” says Lin, “and that has impacted every part of their life—their mental health, their physical well-being, even their ability to feel human. It shouldn’t be a function of financial privilege. You shouldn’t be held back because you don’t have the right insurance policy.”

In addition to Lin, the Right to Walk Foundation’s board includes high-profile amputees such as Paralympic swimming champion Roy Perkins and world champion paratriathlete Jon Beeson, as well as industry veterans from Ottobock and Össur. Lin’s own prosthetist, Peter Harsch, is a major supporter of Right to Walk, and that’s a big reason Lin is putting his name and energy behind the foundation. He and Harsch are kindred spirits, problem solvers with engineering mindsets and a fervor for optimal outcomes, not just adequate ones. As Lin describes their relationship, he drifts back to the subject that dominated his thoughts at the time of his injury.

“People who surf all the time usually have one guy they trust to shape their boards,” he says. “A little bit of foam here or there will make the board feel so different in the water. It gives you the sense of balance and confidence to ride any wave. The same principle applies to your socket, but it’s so much more important. It’s the difference between feeling unsteady on your feet versus taking every step with confidence. Every one of those steps equates to something you want to do in your life. It’s like you’re riding a wave—the wave of life. It all comes down to having that stable foundation.”

“It’s a luxury to have the resources and the support to keep doing the things I do,” he adds. “I don’t even feel like I’m disabled. But that’s because I’ve had access to a well-fitting prosthesis. It’s just a piece of hardware, but it’s a piece of hardware that can give somebody their entire life back.”