By Mary Beth Skylis

When Dr. Ludwig Guttmann became director of the UK’s newly created National Spinal Injury Centre in 1943, life expectancy for people with paraplegia was about two years. Patients typically spent most or all of their time in bed, prone to bedsores, infections, and depression. Rehabilitation was almost nonexistent.

Guttmann, a German neurologist who’d fled the Nazis on the eve of World War II, rejected the prevailing idea that little could be done for immobilized patients. As soldiers wounded in combat began to arrive in his clinic, he promoted an active regimen for patients with severe injuries such as limb loss, neurological trauma, and spinal-cord injuries. Competitive sports emerged as a particularly effective form of rehabilitation, because patients were motivated to participate, and those who did achieved better physical and psychological health than individuals who sat out.

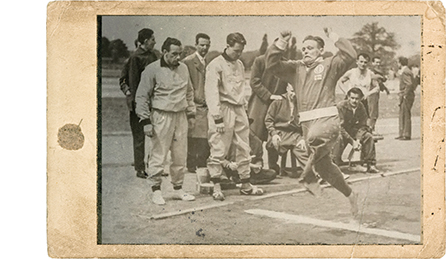

In 1948, with the war over and life returning to normal, London hosted the first Olympics since the 1936 Games in Berlin. Guttman saw this as a prime opportunity to promote the use of sports as a form of physical therapy. In the midst of the London Games, he staged a wheelchair archery competition involving 16 wounded soldiers—14 men and 2 women. The event was dubbed the Stoke Mandeville Games, after the hospital that housed Guttman’s clinic. “Small as it was,” he wrote later, “[the event] was a demonstration to the public that competitive sport is not the prerogative of the able-bodied but that the severely disabled, even those with a disablement of such magnitude as spinal paraplegia, can become sportsmen and women in their own right.”

The Stoke Mandeville Games grew to 37 competitors the following year, 61 in 1950, and 121 in 1951. A small Dutch team of ex-servicemen joined the British para athletes in 1952, creating the first International Stoke Mandeville Games and setting the stage for the Paralympics.

A Global Movement Emerges

Mandeville Games.

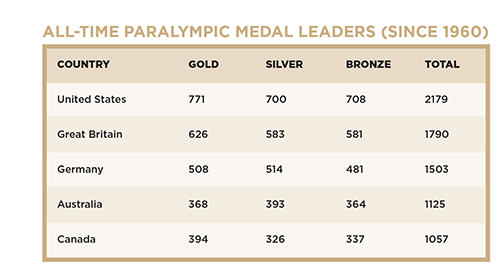

The first Paralympics as we know them—i.e., as a companion event to the Olympics—were held in 1960 in Rome, and the turnout was impressively high. More than 400 athletes from 23 countries participated in eight sports: archery, para athletics, dartchery (a combination of darts and archery), snooker, para swimming, table tennis, wheelchair fencing, and wheelchair basketball. From those first Games, the Summer Paralympics have grown into one of the largest and most heavily watched sporting events in the world. At the 2016 Games, 4,328 athletes from 159 countries and regions participated, and medals were awarded in 22 sports.

In 1964, the International Sport Organization for the Disabled (ISOD) was founded to provide more opportunities for athletes with disabilities. This group was designed to study and provide alternative competitive options for adaptive athletes who weren’t eligible for the Paralympics. ISOD pushed for the inclusion of amputees and people with visual impairments, and both classes of competitors were approved for the 1976 Paralympics. That same year marked the debut of the Winter Paralympic Games.

As the Paralympics began gaining traction, organizations that supported athletes with disabilities became more widespread. The Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association (CPISRA) was founded in 1978, followed by the International Blind Sports Federation (IBSA) in 1980. In 1982 the International Coordinating Committee of World Sports Organizations for the Disabled (ICC) was founded to make it easier to coordinate games for athletes with an array of disabilities. The committee combined a number of organizations to represent athletes with many types of impairments. Under this new organization, groups such as CPISRA, IBSA, ISOD, and the International Stoke Mandeville Games Federation (ISMGF) worked together to create an inclusive environment for athletes with disabilities of all kinds.

In 1989, the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) was established in Germany as a global governing body for the Paralympic movement. Ever since, the IPC’s main focus has been to create an inclusive environment where everyone can engage in competitive sports. The establishment of an organization that could oversee competitive events through a global lens also led to increased interest in the Paralympics.

Innovation Sparks an Athletic Renaissance

Major developments in prosthetics also took place after World War II, as various governments began funding research to improve assistive technology. Prosthetic legs became more lightweight and better attuned to body mechanics. Several years after American college student Van Phillips lost his leg in a 1976 waterskiing accident, he invented a blade-type prosthetic foot for sports that sparked an athletic renaissance for amputees. His first creation was a J-shaped blade based on the hind leg of a cheetah, but he soon moved on to a C-shaped blade, allowing for greater mobility and control. By the late 1980s, Phillips’ company, Flex-Foot, was selling prostheses to the general public. Today, the blade-type foot is almost ubiquitous among track and field Paralympians who compete with lower-limb amputations. Phillips made high-intensity sports more accessible to amputees by providing a higher range of motion and level of support to the human body.

Courtesy Australian Paralympic Committee.

Likewise, major innovations in wheelchair design have occurred since the Stoke Mandeville Games, when athletes competed in ordinary, everyday wheelchairs. Today’s sleek sports-specific models are faster, more maneuverable, more durable, ultra-lightweight, and safer than ever. As a result, they have dramatically increased the level of competition at the Games.

In 2012, Paralympic medalist and bilateral below-knee amputee Oscar Pistorius became a sensation by crossing over to participate in the Olympics. Global sports fans who’d never seen an adaptive athlete before were amazed by Pistorious’s speed and transfixed by his Flex-Foot Cheetahs. But his appearance intensified a debate about whether running blades give amputees a competitive advantage against able-bodied athletes. Four years earlier, Pistorius had been excluded from the Olympics after the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) determined that any device that uses springs gives athletes an unfair advantage. The IAAF’s determination was largely based on a 2007 test that suggested that running blades require 25 percent less energy than a biological human leg. Subsequent studies found that a running blade conferred no unfair benefits, which opened the door to Pistorius’s inclusion in the 2012 Olympics.

No Paralympic runner has been admitted to the Olympic Games since Pistorius, whose fame became infamy in 2015 when he was convicted of murdering his girlfriend. American sprinter Blake Leeper attempted unsuccessfully to be declared eligible for the 2020 Tokyo Games. But adaptive runners, swimmers, and other athletes now routinely participate against able-bodied competitors at the collegiate and high school levels.

There may never be another Pistorius, but it may not matter. The Paralympics have gained recognition as a world-class event in their own right. In a nice bit of symbolism, the 2020 Tokyo Paralympics will be the 16th ever held, matching the 16 archers who participated in the Stoke Mandeville Games back in 1948. Those wounded soldiers, and the forward-thinking Dr. Guttman, would surely be proud and thrilled to see how far their idea has come—and how much good it has accomplished.

Paralympics in which Ottobock has rendered this

essential service. Paris2024.org

Ottobock: Keeping Paralympians in the Games

Ottobock is the longest-standing corporate supporter of the Paralympics. A global manufacturer of prosthetic limbs, orthotic devices, and wheelchairs, the company has played a unique role at every Summer Paralymics dating back to the Seoul Games in 1988.

Ottobock helps athletes meet their goals by providing technical support, completely free of charge, to competitors from every nation. These athletes put their equipment under tremendous strain and often damage their wheelchairs or prostheses devices during high-intensity activities. Ottobock’s on-site repair service centers ensure that every athlete’s equipment functions at the highest levels. All comers are served equally, regardless of whether they use Ottobock gear or another brand.

The Tokyo Games will mark the ninth consecutive Summer Paralympics in which Ottobock has rendered this essential service. As you watch these athletes race, fly, roll, and spin toward their medals, know that it wouldn’t be possible with the 100 or so technical support personnel from Ottobock.

The IPC’s Disability Classification System

To create a level playing field among para athletes with different types of disabilities, the IPC established a set of impairment-based categories, or sport classifications. This classification system ensures that all participants compete against their physical peers, so that outcomes are based on athletic ability rather than degree of abledness.

Classifications are based on various physical criteria, including muscle impairment, range of movement, limb difference, leg length difference, short stature, hypertonia, ataxia, athetosis, vision impairment, and intellectual impairment. In some sports, athletes compete only against others who have the same type of disability, while other sports have integrated competition among athletes with varying (but comparable) disabilities. The severity of each impairment also matters. For more information about the classification rules in each sport, visit the “Guide to the Games” section of Amplitude’s Paralympics website (livingwithamplitude.com/paralympics/paralympic-sports/).