We had hoped to talk to Melissa Stockwell during May, which is Military Appreciation Month, because she was the first Iraq War veteran to wear Team USA’s colors in the Paralympics. But as the Tokyo Games draw closer, it becomes more and more difficult to connect with athletes. In Stockwell’s case, our only window of opportunity fell last Friday, during her brief North American layover between international triathlons in Yokohama, Japan, and Leeds, England.

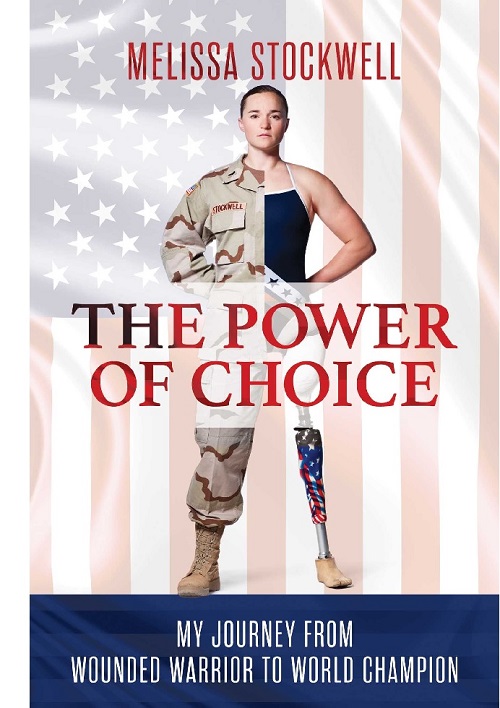

For the full story of Stockwell’s life as a soldier, we recommend The Power of Choice, her 2020 memoir. Our conversation with her last week focused on a different type of battlefield: the campaign to change perceptions about people with disabilities. Stockwell and the rest of the US Paralympic team have a unique opportunity to gain ground in that effort. With NBC devoting more hours and higher visibility to the Paralympics than ever before, the 2021 Games will introduce millions of new viewers to adaptive sports—and to the realities of limb difference and disability.

That puts Stockwell in a role that’s familiar to her from her soldiering days: unofficial ambassador. While she vies for her first gold medal in her third (and final) Paralympics, she’ll also be representing the people of Amputee Nation to the citizens of Ablebodyland. It’s a unique opportunity, and a duty that Stockwell embraces. Our conversation is lightly edited.

You’re part of a small group of Americans who’ve represented the country in both a military uniform and an athletic uniform. Where do you see the parallels and the differences?

It’s similar in that you’re still representing the same ideals. But I think the military uniform represents defending a country, where in an athletic uniform you’re more representing a country. It’s the same kind of principles that go behind it. Either way, it’s a statement that you’re proud of your country and all the freedoms it gives you. That’s true whether you’re defending those freedoms and defending that country wearing camouflage, or wearing red, white and blue and competing on the world stage.

I’ve always been very proud to have worn the military uniform, and one of my favorite parts of every race is putting on that USA uniform and knowing what it means and represents.

There’s a pretty strong military presence on the Paralympic team. Is there any kind of cultural exchange that occurs between competitors from military backgrounds versus civilian backgrounds? Are the things you all learn from each other?

If you’re a Paralympian and you’re at the level of elite competition, you probably have made it there because you have some similar values to somebody who has worn a military uniform. You both have a commitment to wanting to be your best. You have a commitment to being part of a team. You know the importance of showing up on time and holding yourself accountable. Without some of those habits, you couldn’t make it to the highest level. So whether or not you’re coming into it with a military background, I feel like everyone has some similar values already. And we all have the dreams of representing our country. I’ve never really thought about it before, but I do feel there are many parallels there.

Is there ever any sense of good-natured rivalry? At the Warrior Games, there’s incredible camaraderie but the different branches of the service are definitely competing against one another. Within the Paralympic team, is there ever a sense of competition between military versus civilian?

There’s not that big of a separation. You spend too much time together. My teammates and I are together all the time, so there’s a natural back and forth. You joke around with each other and make fun of each other. You do it in the military, too; that never changes. But in my experience on the Paralympic team, it’s not so much that military veterans are on one side and non-veterans are on the other side. You’re all one team and you’re all together. That’s the focus.

When you’re a soldier on deployment, part of the job is to act as an ambassador for your country. For a Paralympic athlete, do you feel an obligation to act as an ambassador for limb loss or disability?

Absolutely. I hope everyone does. I hope everyone who has the opportunity to be in front of an audience as a Paralympian, I truly hope they all view it as an opportunity to showcase who we are and what we do. I hope everybody going to the Games has that same mindset, because this is such a great opportunity to get information out there. It’s such a large audience and such a big showcase—if you’re not proud to be there to represent on behalf of others, you shouldn’t be wearing the uniform on that stage. Because that’s what we’re there for.

Does Team USA provide any support for the athletes to help you play that ambassador role?

There’s media training before you go to the Games, and they give scenarios where reporters might ask a difficult question and you need to deflect. There are certain things that are requested that we just consider off the table. We have athletes of all ages, and I’m one of the older ones. I’ve been around for a bit. But you’ll have younger athletes who are 17 or 18 years old, and that’s a lot to put on somebody.

How much of the media training is about deflecting difficult questions, versus recognizing and seizing on opportunities to proactively educate viewers about limb loss or disability?

We get more training on how how to deflect tough questions. Our stories are kind of the selling point, so there’s not a lot of need to train athletes to talk about themselves and their journey. That kind of comes naturally. It’s more about handling those difficult questions and making that a more comfortable situation. The world is not perfect, and America is not perfect, so there are bound to be some questions that come up. It’s just going to happen. So we need to know how to how to handle those and not put any athletes or countries in a bad light.

Are these tough questions from international reporters who are raising political issues? Or are they tough questions related specifically to the competition itself?

A combination. You might get political questions, or it could be a tough question about classification. Somebody might ask, “Why is this person competing with that person? Doesn’t that seem unfair?” You don’t want to bash the classification officials—or maybe somebody does, and that’s their right if it’s what they want to make a stand for.

Is there an awareness among the US athletes that this is a huge opportunity to make a good first impression on an audience that’s unfamiliar with the Paralympics as an event and as as a gathering?

Yes. And the more widespread the coverage is, the more important it is. We want to continue to get that coverage and to share our stories and get that leverage.

Give me a quick-and-dirty summary of the Yokohama race. Were you happy with your splits and your overall time?

Yes, I was very happy. It was a small field so there was very little competition, but the goal was to win. Even more importantly, I wanted to have a good race, and I was actually thrilled with it. If I can do that again next weekend in Leeds, hopefully I can solidify a spot in the field for Tokyo.

If you win there, does that clinch your spot?

No, there’s a qualifier race at the end of June, and if you win that race then you get an automatic spot. But you can’t count on that, it’s a tough race. So let’s say I come in second at the qualifier. Then the races from Yokohama and Leeds become very important, because there will be a discretionary spot available. If I’ve done very well in other international races, that could be the difference in awarding the discretionary spot. The competition at Leeds will be much greater [than at Yokohama], so it’ll be a good test to get onto the podium and a good opportunity for qualifying.