by Matt Meredith

You don’t have to be a hardcore skier to appreciate this week’s guest post by Matt Meredith, aka @one_armed_wanderer on Instagram. An all-season outdoorsman, Meredith has a particular passion for backcountry skiing, which is arduous and hazardous for able-bodied skiers—all the more so for an above-elbow amputee like Meredith. He’s had to write his own how-to manual for the sport while tuning out the doubts of other backcountry explorers (including well-meaning friends) who thought he’d better stay within the ski-resort boundaries.

“It has been a grand adventure to make this sport my own,” he writes below. His process and philosophy could apply to any adaptive endeavor that requires extra planning, ingenuity, and drive. Check Meredith out on Insta, at his website (https://wmatthewmeredith.com/), or at his brand-new Adaptive Winter Sports Enthusiasts group on Facebook. Our thanks to Matt for sharing his knowledge.

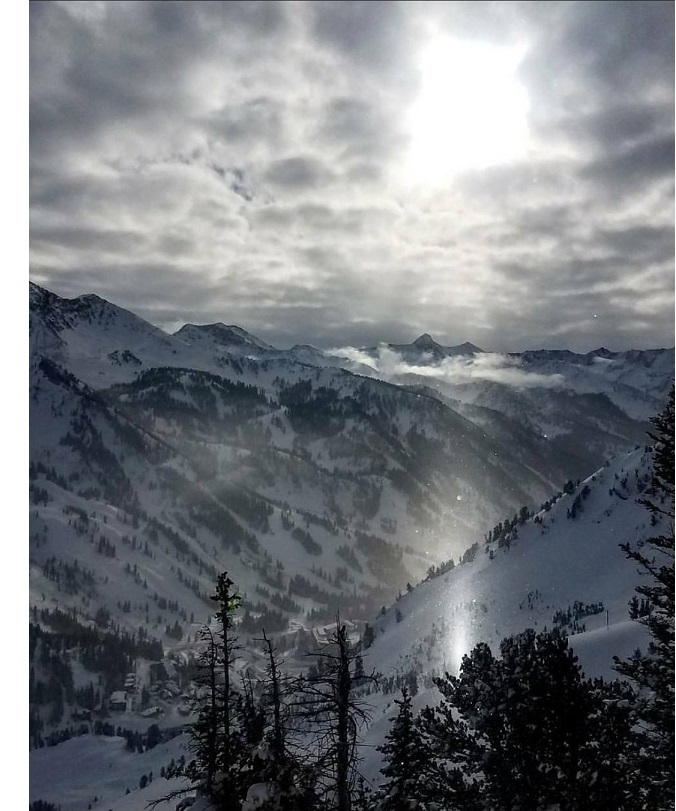

Y Couloir, Little Cottonwood Canyon

“I would never want to backcountry ski with you.”

It was just a casual comment someone made to me during a conversation with a few college housemates (the exact wording is foggily recollected), and it wasn’t the first time someone had expressed doubt about my disability. It was a minor comment, a common thread in the quilt created by a lifetime of quotes casting doubt. Yet, despite it, backcountry skiing was already a true passion of mine. The mountain might be a harsher mistress, but its silent allure overcame spoken adversity.

What makes something a passion, anyway? Is it defined by the feelings it produces, the pounding in your chest? Perhaps it’s an outlet for expression and emotion, something you can grow and foster fulfillment through? If there’s one thing I’m sure of, it’s that the things I identify as my passions produce the most profound of memories—memories formed from moments witnessed, seared into my retinas like a branding iron, bolting along the optic nerve and lighting up multiple regions of my brain, burning into the neurons.

Congratulations if you made it through that neuronal nonsense. In short, glimpsing the beauty of nature through the lens of backcountry skiing has produced many such radical recollections I can vividly recall.

Sometime in high school, circa 2008, while I was skiing at Snowbird Ski Resort in Utah, I recall turning my gaze just across the road. My eye was transfixed as I watched someone ski down Mount Superior, one of the 50 Classic Ski Descents of North America. It was late in the day, and the sun was setting. The light was of the alpenglow variety, bathing the skier in an infinite array of reds, pinks, oranges—a moment of ethereal bliss.

Timpanogos Wilderness

Witnessing this moment of wonder awakened a passion in me. Mouth gaping, I sat in awe at the simple beauty of a skier lacing powder turns together, one after another, across a barren mountain canvas.

Backcountry Skiing: Not for the Faint-hearted

As its name suggests, backcountry skiing takes place far away from the crowded slopes, marked trails, and groomed snow of your typical resort. Cell service is sporadic at best, so you’re on your own if you take a hard fall, break a bone, or get exhausted. That isolation makes it dangerous for all participants, whether adaptive or able-bodied.

The greatest hazards of all are avalanches, which occur regularly on backcountry terrain. One always skis with a partner so that if you get caught in an avalanche, your partner would have a chance to save you or vice versa. It’s a race against time in that type of life-threatening situation. If your partner doesn’t die from the blunt force of a slide, you only have seconds to locate them and dig them out before they die from asphyxiation.

The longer you live in Salt Lake and put down roots, the more likely you will feel a ripple from an avalanche. (They do not call it “Small Lake City” for nothing.) I got acquainted with this crushing consequence in my formative years, when the brother of my dear childhood friend died in a slide. (I never knew the man, but I think of him often when I embark on an outing.) The Utah Avalanche Center visited my middle school to promote avalanche education, and the local news reported on the occasional death. Despite that, I used to duck the ropes to the “side-country” just outside the resort boundaries by myself.

As lives are affected and a community mourns, awareness of the risks were omnipresent in the Salty City, whether you partook or not: Your life, and your partner’s life, are inexplicably linked, a chain of consciousness and capabilities. Your lives are in each other’s hands.

Note the plurality of “hands.” I am a congenital upper-arm-amputee, the result of amniotic band syndrome. When I backcountry ski, my partner places their life in my hand.

I believe that’s what prompted my college friend to say, “I would never want to backcountry ski with you.”

Wasatch Mountains

Thankfully, most people have felt differently. Whether consciously or intuitively, they understand that an adaptive backcountry skier—even more than an able-bodied one—must think through every step of their process to enjoy the sport safely and responsibly, making extra preparations and weighing every contingency. That mind-set makes me at least as well equipped for emergencies as most backcountry travelers. And it’s the mind (not the hands) that matters most in a life-or-death moment.

Adapting to Backcountry Skiing as an Amputee

I’m self-taught in just about every area of my life, including backcountry skiing. Regarding “Adaptive Tips and Tricks,” I didn’t have any guidebooks or blogs to follow, nor any YouTube channels or Instagram accounts. My adaptive-sports role model was Jim Abbott, a one-handed major league pitcher. (I don’t even like baseball, but I certainly admire his role in breaking that sporting barrier.) Aside from him, my role models were all able-bodied; in the early days of the Internet, adaptive athletes just didn’t have representation in mainstream media. Even today, I’d say they still could be better represented.

Regular downhill skiing is readily adaptable for one-handed bodies, but backcountry skiing is where things get complicated. I’ve had to devise my own solutions for skinning (or skiing uphill), transitioning (adding or removing skins to switch between uphill and downhill skiing), gear selection, and other aspects of the sport. I won’t go into the details here, but you can learn more at my Adaptive Winter Sports Enthusiasts group on Facebook. I’m also creating a full Instagram Guide to Backcountry Skiing (@one_armed_wanderer) and a YouTube channel to cover adaptive skiing at the resort and in the backcountry.

The one piece of advice I’ll share here is this: Be careful when selecting avalanche equipment. Make sure you can easily manipulate your beacon, probe, and shovel. I am a massive fan of the Mammut Alugator Pro. It possesses several qualities to make it perfect for the one-handed skier, with features like a T-Based handle to fit under your armpit for leverage, an extendable handle to allow more range of motion, and a “hoe-mode” to allow a different form of snow movement if one becomes tired.

Mount Flagstaff Face,

Little Cottonwood Canyon

Due to thorough preparation, good decision-making, and perhaps some luck, I haven’t had any rescue scenarios to test my adaptations. I have, however, been able to ski some beautiful peaks with technical ascents and descents. I have not felt held back one bit. I focus on what I can control, like technique and fitness. Typically, I beat my friends both up and down the slopes (not that it’s a contest).

It has been a grand adventure to make this sport my own. As an amputee, at times, I’ve found it lonely and intimidating venturing into new sports. It can be hard to find a sympathetic ear, let alone an empathetic one, for struggles encountered. Yet the scene is changing; more adaptive folks are taking up backcountry skiing. If you’re one of them, or you’d like to learn more, I would love to share this great passion with you.

Oh, and by the way, as pleasing as it was to watch that skier rip down Mount Superior a decade-plus ago, I found it eternally more satisfying when that same fresh powder was gracing my goggles.

Passion personified.