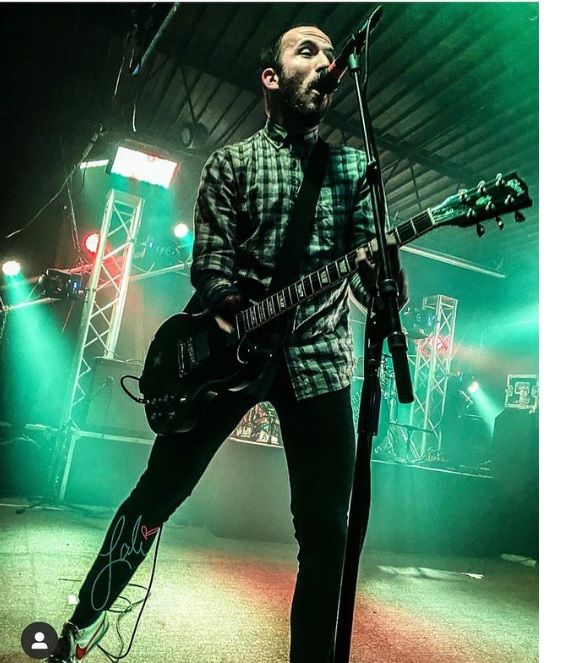

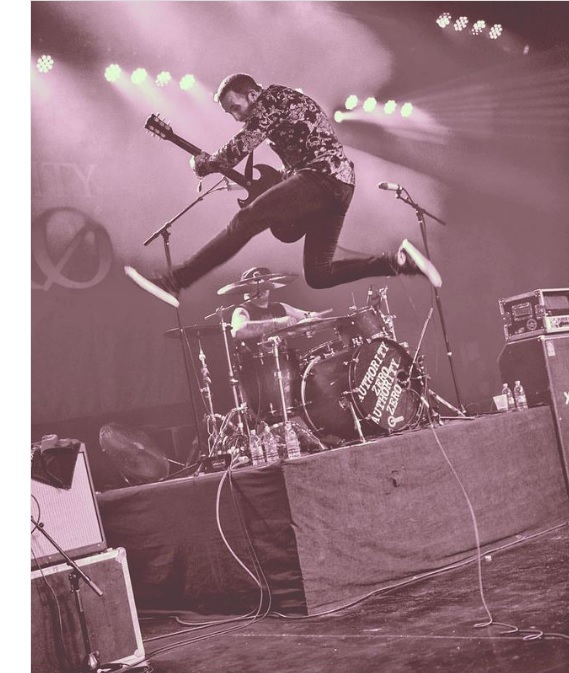

It got our attention last fall when the single from Dan Aid’s latest project, Big Hearts Club, started getting airplay on an indie radio station we like. We already knew Aid performs with a limb difference (and had him penciled into the lineup of our all-amputee band), but that fact never made it into the DJ’s patter. It was just a strong debut record by a new local act—which is exactly how Aid would want it. In a decade-plus as a rock guitarist and songwriter (including four years touring internationally with Authority Zero), he has neither concealed his limb difference nor called attention to it. It’s just not that central to the ideas he wants to explore or the experiences he’s trying to create.

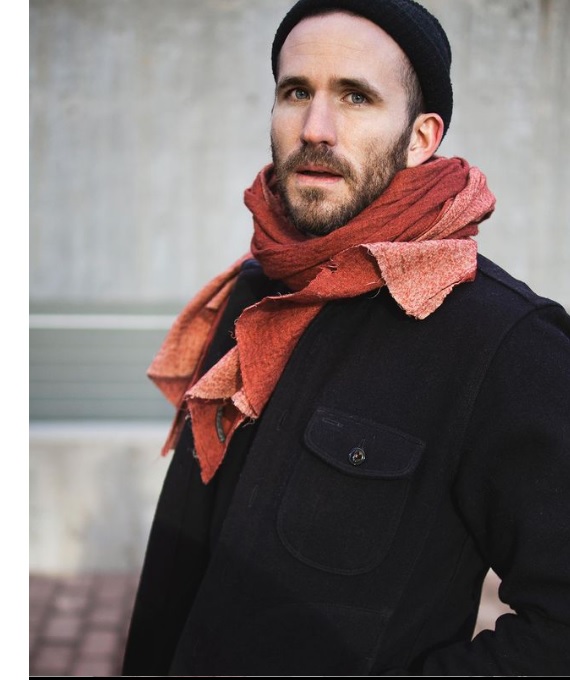

Little did we know that there’s this whole other side to Aid’s career. He’s started to land some impressive acting gigs, including a recurring (and deadly) character on NBC’s Good Girls and a part in Tentacles, the most recent installment in Hulu’s “Into the Dark” movie franchise. Acting has presented Aid with new opportunities to push boundaries, poke at conventions, and tell stories that don’t fit comfortably into familiar categories.

You can follow him on Instagram @dan_aid and check out some of his solo music on Bandcamp. Keep an eye open for his next appearance on Good Girls, which is due in a couple of weeks or so (Episode 4 of the current season). This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Is there such a thing as a community of amputee musicians?

Not that I know of personally. I’m not sure there needs to be one. For me, making music is all about creating something that I can give away to other people. It’s not real for me—it doesn’t come full circle—until I get to share it. So if someone doesn’t have a limb, but they’re playing an instrument in a way that brings them joy, and they’re able to bring other people joy through that process, that’s what makes it relevant.

In other words, people don’t pigeonhole Stevie Wonder or Ray Charles as “blind” musicians; they’re just musicians. The fact that a musician does or does not have a limb difference is kind of moot.

When I was first coming up, I remember having conversations with friends and saying things like, “I’m the one-handed guitar guy! That’s gotta be so crazy to people, it’s gonna make its own career for itself.” And my friends would be like, “Yeah man, it’s crazy. Once everybody knows about it, it’s just gonna blow up.” And none of that is actually true, because everybody has had something traumatic happen to them. Especially in the artistic community—it’s usually something traumatic that draws them into creating art. And that trauma, in and of itself, is not enough to keep people’s attention. You have to go beyond your trauma. You have to be using the lens the trauma has given you to say something through your music or through your lyrics that invites a bigger community.

I don’t think it’s an accident that I got more into performing after I lost my arm. You’re seeking acceptance. You’re asking, “If I put my body in front of people, will I be accepted or loved? What’s gonna happen if I show people this body?” That’s a really interesting thing to pursue, and I’m still pursuing it. I think I will forever be curious about that, because it changes as I change and as this body gets older, as I become involved in different things. It’s an evolving relationship. It’s not something you figure out. It’s one of the questions I’m most curious about, and continuing to perform helps me keep a little barometer of where I’m at.

Do you feel like the audience is also evolving while you’re evolving? Are they receiving you differently over time, as perceptions of disability change?

The reactions are really interesting, A lot of people don’t even notice that I have one hand when they’re watching me perform. I just taught a kid [music lessons] for 22 weeks over Zoom, and just the other day he said [for the first time]: “You have one hand?”

The reactions to you having one hand in the world are so varied. They can often be beautiful, and other times people’s reactions can be pretty misplaced and hurtful. But I do think things that are different in the world invite conversation, and I like conversation. I just want to make sure we don’t further traumatize people through the conversation.

What has the last year been like for you, given the lack of performing opportunities?

It has been incredibly tricky. I did a couple of live streams that friends put together, and that’s really been about it on the performance front. The other main thing I’m doing this year is teaching for a nonprofit a buddy of mine started about ten years ago, called the Musical Mentors Collaborative. The idea behind it is to identify kids who don’t have the resources to afford instruments or lessons and connect them with a teacher. They’ve specifically gone after kids who are living in the foster care system or who are experiencing homelessness in some way. It’s worked out really beautifully [during COVID], because it’s really hard to get work without being able to tour or play in your orchestra. Musical Mentors is helping kids who wouldn’t otherwise have access to these life-changing experiences, and it’s helping artists pay the bills and buy groceries.

And then on the acting front, I was out in LA for a week, filming an episode for a show I’m on called Good Girls on NBC. That’s not gonna air until later this year.

I don’t think I realized you were an actor.

I started acting in grade school and did theater in high school, and after I graduated I spent a year studying theater at NYU. I was pretty disillusioned by what I saw. I saw these really talented people who were really struggling to create careers. I didn’t feel at home in my body or in my brain, and I had totally given up the band I was in at the time, Letters from the Front. I didn’t even take a guitar with me when I moved to New York, and I was really missing that. So I transferred to the University of Colorado at Denver, got a degree in music business, started putting bands together again and started playing local shows and doing that whole thing.

It took me years to get back to acting. Someone I went to [Denver] East High School with continued acting, and she ended up doing some international theater tours. We kept in touch because we saw each other trying to do art in different ways. She had recently moved to LA, and she mentioned to me to her manager. He’d had a part come across his desk and sent it to me to audition for. I didn’t get it, but then the second role he sent me was for this show on Showtime called SMILF. And I got that role. I was lucky enough to be in a couple episodes in the second season playing Hank, the tattoo artist and romantic interest.

I remember that show. It was little bit of a boundary-pushing idea.

What Frankie Shaw, the creator, did with SMILF was really cool—the idea of having a female lead as a single mom and really addressing poverty and race in the way that she did. I feel very fortunate I got to be a part of that show.

After SMILF, the next thing that came along was Good Girls. My character was supposed to be recurring last season, which was Season 3, but we ended up only getting to shoot one episode because of the pandemic. But they picked it back up this year, and I feel really fortunate that they kept the storyline that my character was in and wrote me back into the fourth season.

Are you acting with a prosthesis in these roles? Are you playing amputee characters?

On SMILF, I don’t think the character of Hank was written as an amputee. But once I got the role, Frankie really invited conversation around the character, and it’s incredible as an actor to have the creator ask for your input. We got into deep conversations about who that character was and how he might interact with her character in these situations. I remember specifically on the second episode I did, during rehearsal we had these really intense and beautiful conversations around different people’s sexual experiences in the world. Because we were shooting a sex scene the next day, so we were talking about our own relationships with our bodies and with sex, and how that brought each of us to become the adult they are now.

I’ve never gotten to have a discussion like that with other creatives around character and around just what we might be able to to show an audience if we are aware of who we are in our bodies as we enter into this scene. It was kind of revolutionary, because I was playing the character as an amputee even though he wasn’t conceived that way.

My character in Good Girls was written as a double amputee. During shooting, I wear this little prosthetic thing they built that mimics my left arm nub. And then they remove the rest of my arm [from the shot] in post-production.

It’s not often that you’ll see any kind of character with a disability in a mainstream network TV show. I honestly can’t think of a single double-arm amputee from a network show. Where does this character fit into the storyline?

He enters the show—you know, the three women in the show are these sort of suburban moms gone bad. That’s the basic premise. They each have financial things that come up in their lives that force them into this life of crime. And I come up as a hit man they’re looking to hire to bump off their boss.

A hit man . . . . as a double arm amputee. So, like, how are you supposed to bump anyone off?

I’m an explosives expert.

Got it.

When they meet me, and this guy with no arms walks in, they’re all like: “How are you gonna kill anybody?”

I have to say, I’ve been impressed by how the writers on this show have utilized limb loss to create comedy. I’ve seen people try to create something funny in a grotesque way, like somebody getting a hand chopped off or something cartoonish. They think it’s going to play violent-funny. And I think violence can be funny, but most of the time I don’t think it’s that successful. So the writing around the limb difference on Good Girls I think has been pretty refreshing.

This is kind of pleasantly shocking to hear. It’s very rare to find edgy disabled characters anywhere, much less on network TV.

Any time someone who we’ve labeled as different gets more of a spotlight on them, it takes a while for people to treat them as more than some token thing, because that’s the way we’ve been conditioned to introduce new ideas into culture. And then slowly we create understandings that aren’t just defined by what makes those people different, and we start actually finding what can be really human and funny and telling about them. Because those stories are inherently more interesting. And as we go through this, I think we’re gonna find out we’re telling new stories. There’s so many stories that we haven’t told yet.

About 95 percent of the roles I’ve auditioned for are military veterans. I haven’t booked a single one of those. But what’s interesting is that the roles I’ve actually booked are ones where I am not the actual body type. My character on SMILF wasn’t written as an amputee, but that’s how I’m playing him. And now I’m playing a character who’s a double amputee, and I’m not that.

Are you pursuing both acting and music about equally now, or are you just taking what comes?

So one of the biggest things that happened this year is that I left Authority Zero. That’s been my main job for the past four years. We did four records together in that time, and between that and touring it was about six to eight months of work every year. That was an amazing experience.

But as I started to get these acting opportunities, I came to the realization that I can’t necessarily do both, at least at this point in my career, because of the way both those worlds work. When [acting] opportunities come up, you have to be able to say yes to them very quickly. There’s not a way you can really look ahead and know what your schedule is going to be, at least with the amount of control over my career that I have at this point.

In general, I’ve found trying to make any sort of career as an artist kind of requires saying yes to everything, and then saying no when you have to. As much as I try to push into stories that are different, I also always have an eye toward how do I sell this or make this viable to an audience? You may have the most brilliant concept in the world, but getting anyone to invest in it takes a lot of luck.