By Élan Young

From mountains to sea, intrepid amputees are getting around everywhere. Taking up an outdoor activity during summer can be a great way to experience improved overall health and wellness, and in many cases it can be done without a big investment. Amputees who have found satisfaction in outdoor activities offer some common advice:

• Get outside, even if it’s only for ten minutes a day.

• Explore limitations; then be willing to push them.

• Recognize the mental health rewards that come with pursuing an outdoor sport are just as important as physical rewards.

A whole host of activities are available to amputees who are simply willing to try something new.

Getting Connected Versus Going Solo

Group experiences can offer a feeling of connection and a pathway to experiencing activities that one might otherwise feel intimidated to try.

However, Nate Denofre—a bilateral below-knee amputee probably best known for braving the alligators and strong currents on a 2,300-mile canoe trip along the Mississippi River with his wife, Christa—says to start, even without a group to accompany.

“The toughest thing overall in my opinion is to find other amputees to join with. My advice is to research, research, research, and you’ll eventually find something,” he says. “Most importantly, start doing things you love, and you never know who you’re going to meet. It’s a very big world. You don’t have to paddle the whole Mississippi River. Just do a little bit every day. You’ll get outside and feel better little by little. Doing something, even if it’s by yourself, is still better than doing nothing.”

Others say that utilizing social media can be a way to get connected to the bigger world of adaptive sports. Sharing your activities on social media and using hashtags to connect to the adaptive sports community can also help change outdated cultural attitudes about those with disabilities by providing visibility.

“Putting yourself out there on social media can be vulnerable, but it can also help you establish connections with others,” says Matt Meredith, an athlete with upper-limb loss from birth due to amniotic band syndrome. “If you don’t have a local community, social media can offer an avenue to experience a bit of a larger community and to place yourself in a tribe.”

Meredith Instagrams his adventures at @one_armed_wanderer. Some of his favorite hashtags are:

#adaptiveathletes

#bodypositivity

#representationmatters

#inclusivitybenefitseveryone

“I typically like to do things by myself,” says Meredith, who frequents the mountain trails in Utah. “Sometimes I meet up with people to get the skills and then go by myself to troubleshoot it.”

Safety

Safety is an important consideration when choosing a sport, and if a person is not confident trying new activities, learning with an instructor can offer immeasurable benefits. However, adaptive athletes also emphasize that it’s important to know thyself—that is, to know one’s own limitations and comfort level before trying new activities.

“We can all dream up a thing, but we need to learn to accept our own limitations,” says Denofre. “That’s how you learn what you like and don’t like to do. That’s where groups can come into play. Talk to other people and see what works for them. Keep an eye on the group before you get involved.”

Learning to Soar

Skydiving, paragliding, and parasailing are just three activities available to amputees that don’t require bearing weight on a residual limb. Tandem flights offer an opportunity to experience the sport without a long-term commitment, and the benefits can have a lasting impact on one’s emotional health.

Tyler Turner, a bilateral below-knee amputee due to a freak skydiving accident, continues the sport that resulted in his limb loss. As a skydiving instructor and overall adventure athlete, he thinks that all amputees should experience skydiving. “I’ve seen that the adrenaline dump really helps a person reclaim a sense of well-being and purpose,” says Turner. “Skydiving offers a whole new way to experience freedom, and that is an invaluable opportunity, especially for any amputee who is struggling with depression and mental health issues.”

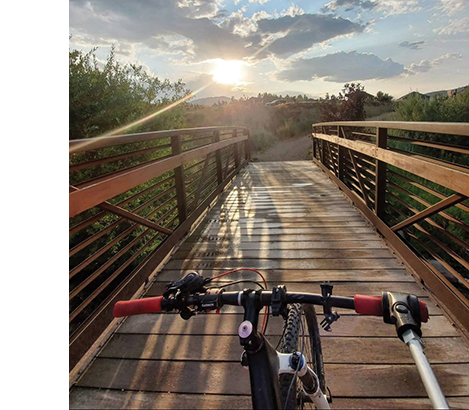

Cycling

Cycling is one of the best sports for amputees of all levels to experience the rush of a body-powered machine, with options for road biking, mountain biking, and handcycling. Meredith learned how to ride a bike when he was about 15 and has not stopped since. In 2013 he picked up mountain biking with the help of a prosthesis from Shriner’s Clinic in Salt Lake City, Utah, and even offers to let people DM him through Instagram if they need help figuring out modifications.

“I don’t think an upper-extremity prosthetic limb is necessary for mountain biking unless someone is really committed to sports,” he says.

Lower-limb amputees may enjoy various models of handcycle bikes, which are three-wheeled, hand-powered bikes with options for racing, recreation, and off-road adventures.

The Healing Waves

Swimming is one of the healthiest activities around, and for amputees it offers a range of ways to engage with or without adaptive equipment. Going without a prosthesis can help an amputee feel freedom with a sense of weightlessness. However, for those who want them, prosthetic fins are available to help both upper- and lower-limb amputees kick and freestyle.

For those with access to the ocean, surfing offers a way to feel connected to nature while experiencing the benefits of improved balance and greater self-confidence. Depending on one’s level of amputation and comfort in the water, catching a wave with a surfboard doesn’t necessarily require the use of adaptive equipment. Specially trained guides with adaptive sports programs can help someone light a fire within and help someone feel empowered on a board.

Turner, who is also a surfer, has seen people experience huge mental and emotional breakthroughs from surfing. “Being in the water and feeling the movement of the waves offers a way for amputees to experience motion very differently,” he says. “They often experience feeling connected and free.”

Running, Walking, and Hiking

Bjoern Eser, a left above-knee amputee and blogger at theactiveamputee.org, lives in Germany and takes advantage of the rolling hills of Europe. For him, enjoying adaptive sports does not have to require more than just the desire to go for a walk in nature.

“Once I was out of the initial rehabilitation center, and I could walk for a kilometer, I started getting my basic level of confidence by walking on different ground.”

He walked up and down stairs, on uneven surfaces outside, and even tested his footing on snow and ice. “I just pushed my limits a bit going up the hills, and very often I did that by myself.” For this, the only thing he needed aside from his prosthesis was a pair of good, reliable hiking poles.

Eser became an amputee in 2005 after long-term use of an endoprosthesis during his bout with childhood cancer and says that transfemoral amputees need to go through a gateway of feeling comfortable with their prosthetic knees.

“I think that’s the key to unlocking other activities being outdoors,” he says. “When you engage in the initial walking, you can push the limits by yourself. You can make it part of your daily exercise routine and really push it from 1K to 5K, 10K, 20K—whatever you want to with your gear on your back or without gear.”

Meredith likes to find time for trail running, and with upper-limb loss, his no-tie running shoes by Salomon offer a lot of convenience.

“I’m not sure I would even know how to lace shoes at this point,” he says. Meredith thinks that if more companies were aware of the challenges faced by people with disabilities, they could improve design for everyone.

Backpacking

After getting comfortable with hiking, the first step to backpacking is to determine how best to carry a load of about 35 pounds or more.

Meredith, whose amputated side is not as developed muscularly—he calls it a work in progress—says that backpack straps can cause pain, so he opts for backpacks with stretchy material that help provide more comfort, like the Salomon Out Night 30+5 Unisex Hiking Bag.

He also finds that backpacks that unzip from the back panel—instead of requiring the user to stuff everything in from the top—offer a way to eliminate a lot of stress and hassle for upper-limb amputees. Items with magnetic zippers are also on his list of favorites for camping and backpacking.

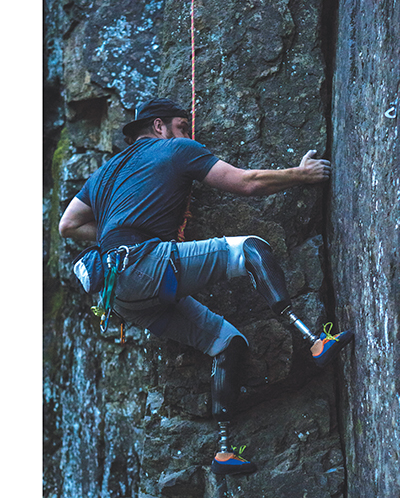

Rock Climbing

Many cities now offer climbing gyms with great instructors. Eser says that climbing is a great sport for lower-limb amputees because it doesn’t require much equipment beyond a harness. As he developed more confidence, and with help from a friend who was a rock-climbing instructor, he invested in a climbing foot, but only after he knew he would enjoy the sport for a long time.

Turner, who was a rock climber before becoming an amputee, still struggles to accept his new level in the sport because he longs to travel through the mountains with the same speed and grace he once had. However, he has also seen amputees try the sport for the first time with great success, providing a great sense of accomplishment.

“Climbing gyms are great because the variables are very controlled,” he says. “It is a good physical activity to get the body moving and maybe overcome some fears in a safe way. I am personally a big fan of climbing outdoors because it provides that sense of adventure that I’m always looking for.”

Meredith also climbs, but without the use of prosthetic aid. Growing up, he went with friends who were generous with their help but feels their helping so much may have been a detriment. He thinks that autonomy in athletics is key to a good time. Then he attended Paradox Sports, an adaptive organization based out of Colorado, where an adaptive climbing guide taught him how to tie a figure-eight knot to be able to rope himself up. “That was debatably a better experience than actually climbing,” he recalls. “Having that bit of knowledge gave me so much independence.”

Paddling

Denofre is an adaptive guide with Strong Ports, an organization he founded early this year, who enjoys a range of activities and is passionate about getting amputees out in the woods to experience greater connection with nature. He is an avid backpacker, but after a hip replacement surgery, he wanted a lower-impact sport, so he turned to paddling.

His voyage along the Mississippi marked the first time that a double amputee had completed the journey, and he says that paddling is very accessible for lower-limb amputees. In fact, the only modification he made to his 17-foot canoe was to purchase a folding seat.

“It certainly looked funny, but it saved my back and felt good to take a break, kick back, and look at all the scenery,” he says.

Upper-limb amputees can also find an array of prosthetic hands that are designed to fit a kayak paddle or a canoe oar.

Organizations

Many organizations exist to connect people to adaptive sports. Search local areas for rehab hospitals and amputee support groups for more opportunities to connect.

Challenged Athletes Foundation: challengedathletes.org

High Fives Foundation: highfivesfoundation.org

K2 Adventures Foundation: K2adventures.org

Paradox Sports: paradoxsports.org

Roxy Davis Foundation: roxydavisfoundation.org

Stoke For Life Foundation: stokeforlife.org

Stride Adaptive Sports: stride.org

Team Catapult: teamcatapult.org

Wounded Warrior: woundedwarriorproject.org