Colton Eberhardy wasn’t sure he wanted to live. Losing a leg helped him find his sense of purpose.

By Chris Prange-Morgan

It’s hardly unusual for teenagers to get overwhelmed by their emotions. Adolescence ushers in a cascade of changes, making it difficult for teens to identify what they’re feeling, much less express it in a healthy way. On an August day in 2018, things reached a breaking point for 15-year-old Colton Eberhardy.

“It started in middle school, actually,” says Colton, who grew up in rural Wisconsin. “I wanted to be a man—you know, the tough image. I didn’t want to cry or feel my feelings. I kept everything in and didn’t really want to tell anyone. I had a pain and a sadness that just sat there like a ball in the pit of my stomach—horrible feelings that actually made me physically sick sometimes. As they grew and grew inside of me, I really didn’t know where to go with them. It was getting so bad that I was just done. I wanted out.”

Colton didn’t see an end to the pain. But he needed to let the people in his life know how badly he was hurting—and give them a chance to help. “So I put a random bullet in a shotgun and shot myself in the abdomen,” he says, “because that was where I held all of my feelings.”

Colton’s mom, Stephanie, recalls the terror she felt as she ran to her son’s side. As a medical professional, she could tell immediately that he had probably severed his femoral artery and sustained extensive, potentially irreversible damage to his internal organs. “I couldn’t let my son die,” she says. “My heart was breaking, and I wanted to panic, but I couldn’t. My protective instinct kicked in as I saw him bleeding out and tried to stop it.”

Colton, meanwhile, experienced what he describes as an out-of-body experience. “I knew my mom was a physician assistant and that she would do whatever she could to save me,” he says. “But I was also sad and confused and feeling kind of hopeless. So I think this was my way of leaving it up to fate to see if I lived or died.”

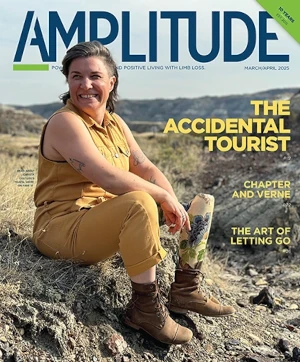

Photos courtesy Stephanie Eberhardy.

Fate didn’t reach a conclusion for many days. Colton slipped into a coma. Stephanie knew that even if her son survived, he faced a long road of recovery and rehabilitation. “It was touch and go for many, many days.” she recalls. “From one day—one moment—to the next, I didn’t know if we would lose him. I prayed so hard: ‘God, please don’t take my son. You can’t take my son. He has so much to offer this world.’”

When he finally regained consciousness and his condition stabilized, Colton faced a multitude of surgeries to repair the damage to his abdomen. He lost a kidney and most of his large intestine, requiring the insertion of a colostomy bag. And, just as Stephanie feared, the gunshot had destroyed the vasculature supplying blood to Colton’s left leg. Although doctors tried to preserve the upper portion of the limb, they eventually had to perform a hemipelvectomy, removing all of his femur and the left half of his pelvis.

Just before Christmas, Colton’s body had finally healed enough that he could come home from the hospital. But the psychological healing was only beginning.

“I was always on some kind of pain medication and couldn’t think,” Colton says. “I was either recovering from or getting ready for some kind of surgery. Plus, I was going through all kinds of hard feelings. I lost my leg, had a colostomy bag, and didn’t know what my future would look like. And that weighed really hard on me.”

While science and technology are making rapid progress in addressing the physical challenges of limb loss, in some ways the mental health challenges remain much more daunting. As an amputee with a background in mental health, I know well the inertia that accompanies pain and struggle. Depression and anxiety always appear to be lurking around the corner, especially when we’re dealing with socket-fit issues, phantom limb pain, health setbacks, or an inability to live the life we envision—even if only temporarily.

The Amputee Coalition of America cites numerous factors that can influence how well an individual bounces back from limb loss and deals with setbacks along the way. Level of amputation, age, personality, financial means, support system, and physical and social environments are all key factors in rebuilding life after facing limb loss and other health challenges. Key questions include: Have you coped with difficult situations before? Do you feel a sense of control despite the loss? Do you have a community of supportive people in your life—family, friends, or peers? Can you find meaning and purpose and connection to help offset the pain and struggle you experience?

While losing a limb is a life-changing experience for anyone, it can be especially hard for a teenager—especially one who’s dealing with other health challenges, as Colton was.

“I don’t know what I would’ve done without my mom.” he says. “My school, my friends, and a lot of people came into my life to help me. I learned who my good friends were, because they stuck by me even when things were hard. Now we laugh and joke. We go for walks at night and look up at the moon and the stars, because the moon and the stars are amazing.”

“From where he was to where he is today, I’m just so thankful he’s still with us,” says Stephanie. “As a medical provider, I’ve seen so many deaths due to suicides and drug overdoses. The isolation is so profound these days, and if Colton can help one person feel less alone, it makes my heart happy to know his story has helped someone.”

Colton started paying it forward soon after he returned to classes in early 2019. One of his high school classmates had died by suicide at around the same time Colton shot himself. In response, the school spearheaded the Sources of Strength (SOS) Program, whose mission is to prevent suicide by increasing help-seeking behaviors and promoting connections between peers and caring adults. As the survivor of a self-inflicted gunshot wound, Colton brought a unique perspective on how mental health can go off the rails—and how it can recover. When the initiative sponsored a run for suicide prevention and awareness, Colton enthusiastically took part.

“It was pretty amazing to see the whole community come together to address this real need to address mental health concerns in our community.” Stephanie says. “Colton was out there in his wheelchair, spraying colored powder everywhere and just having fun. It was a sign of hope—a symbol that, even after the rain and the darkest of days, rainbows can still be found.”

But as Colton learned, rainbows don’t always appear by magic. You have to go out and find them. Colton chased his pot of gold in partnership with his prosthetist, David Rotter, setting the objective of walking across the podium at his high school graduation to receive his diploma. It was an ambitious goal for a hip-disarticulation amputee, given the challenges of fitting a prosthesis with no residual limb. But the mission lent structure and purpose to Colton’s recovery.

“I learned that it’s important to keep moving ahead,” Colton says. “The way I see it, we’re all on a path, and sometimes you face obstacles—like the grass itching your foot, a tree in your way, or a mountain that you have to climb. Amputation is like a mountain—and you may find a cave on the way that you want to sit in, because it’s cozy. You’re tired. It might be raining. You’re tempted to stay in that cave because it’s comfortable, but it’s also bad and dangerous because it traps you inside, and you need to get out. You need to stay on that path and where it takes you.”

Remaining on course doesn’t always feel good, Colton adds, but he’s learned to keep pushing even when it hurts. “Sometimes I put in a sad movie to have a good cry,” he says. “I’m not gonna lie, it’s still hard sometimes. Having a hemipelvectomy hasn’t been easy by any means. But I don’t stay stuck in that cave anymore. It’s important to just keep moving.”

That imperative carried Colton to the first destination he’d set for himself: He did walk in his graduation ceremony, crossing the stage under his own power. Now 19 years old and working two jobs, he’s planning to attend college in the fall and pursue a career in either writing or engineering.

“I have an idea of what I want to be now,” Colton says. “I think you need to find that thing you enjoy to give you motivation—and to follow it. That’s what keeps you going. I’m really proud of myself that I survived through it all, that I can even look back after all I’ve been through and smile because I’m still here. That life path—there will be jungles with wild things. There will be storms and sunshine and rain. There will be potholes and valleys and mountains to climb. But I can tell you that if you stay on that life path that you have no idea where it’s going, one day you’ll look back and be glad that you did.”

“The life of an amputee can be hard sometimes,” he adds. “But everyone has a story. Our stories merge on our different paths. But I can tell you that if you’ve kept going in spite it all, you’ve already won.”

Mental Health Resources for Amputees

There’s no one-size-fits-all formula for maintaining mental health as an amputee. But there’s a robust list of go-to strategies to support emotional well-being for people with limb loss. If you’re struggling to fend off feelings of hopelessness, here are some low-cost/no-cost steps you can take.

Connect With Other Amputees

- Request a certified peer visitor from the Amputee Coalition

- Attend a support group meeting (virtual platforms enable you to participate remotely)

- Strike up conversations at your prosthetist’s office

- Find your tribe on social media

Stay Physically Active

- Join an adaptive sports program

- Do exercises at home (Move United’s OnDemand platform offers many options)

- Work regularly with a physical therapist or fitness trainer

Stay Mentally Engaged

- Set goals and chart your progress to hold yourself accountable

- Keep a diary, journal, or blog

- Volunteer for a nonprofit organization that supports amputees