The influencer’s new Apple TV+ series takes a big step for disability representation in the entertainment industry.

“I just don’t think amputation is a great story vehicle,” Josh Sundquist says.

That’s an eye-opening opinion, coming from one of the world’s most successful amputee storytellers. But if you’ve read any of Sundquist’s bestselling books, caught any of his standup comedy, or watched his TikTok videos, it makes perfect sense. When Sundquist wrings laughter out of his own experience with limb difference, he’s almost always addressing a much broader theme: difference. It’s the same vein comedians have been mining since ancient Greece—the folly that arises when an outsider encounters a new culture, questions its arbitrary rules, and exposes its nonsensical blind spots.

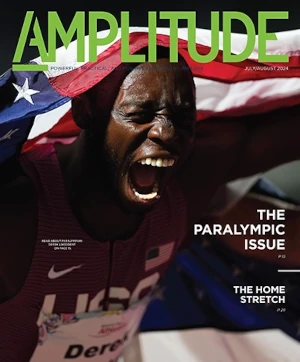

Best Foot Forward. Photos courtesy Apple TV+.

As a hip-disarticulation amputee in a two-legged world, Sundquist easily qualifies for outsider status. But that’s only a small part of his repertoire. He weds observations about limb difference with more universal riffs on the absurdities of intrafamily relations, the glorious futility of romantic attraction, and the heroically floundering transition from adolescence to adulthood.

The resulting combination manages to be simultaneously familiar and unique, normalizing limb difference even as it entertains. That’s the intention of Sundquist’s latest project, Best Foot Forward, a family-oriented series debuting this month on Apple TV+. Produced by an award-winning creative team, the show is loosely based on a period of profound transition from Sundquist’s own youth. But not the one you might think.

“It’s about a boy who’s been homeschooled his whole life, and he’s transferring to public school for the first time,” says Sundquist, who made that passage himself shortly after losing his left leg to childhood cancer. “The inciting incident is not [the amputation]. The primary vehicle is this fish-out-of-water experience of going from a narrow, homeschooled social bubble into a public school.”

Although the series’ protagonist, Josh Dubin, does have a limb difference and wears a prosthesis, that’s far from the most interesting thing about him. What makes him exotic are his out-of-step assumptions about friendship, dating, homework, grownups, and everything else the average kid cares about.

“Sometimes people can overestimate how interesting disability is,” Sundquist says. “And they underestimate how interesting it is to focus on a whole human being, a certain part of whom is a disability or limb difference.” He has done as much as anyone to elevate the latter form of storytelling over the last decade-plus. Best Foot Forward continues that trend, while breaking new ground in onscreen depiction of limb difference and establishing a new blueprint for disability entertainment.

Sundquist sat down with Amplitude to explain how the series came together and what he hopes it can accomplish. Here’s part of our conversation, edited for clarity.

Where did the idea for this show originate? Did you come up with the concept and shop it, or did someone pitch you the idea?

Many people have approached me with ideas for shows about amputees. These were unscripted shows or documentaries about me where I would follow amputees going about their lives being sad/inspirational figures. I don’t necessarily have a problem with a show like that, but it’s not that interesting to me. I don’t think you can generate season after season of shows about being an amputee.

A production company called Muse Entertainment USA approached me after having read Just Don’t Fall [Sundquist’s 2010 bestseller]. What I loved about Muse’s idea was that they wanted to do a show about a homeschooled kid going to public school and learning a whole new environment. That’s a very narrow sliver of my book—it’s literally one chapter—but it’s a classic comedic trope, and it’s a story engine that I can see going on for multiple seasons. So I loved that idea. It was better than anything I’ve ever been pitched.

in Best Foot Forward.

Once you’d agreed on the premise, how did it get turned into an actual series?

We started out with a writers’ room. There were 12 people, including me. Five of us had some sort of physical disability, which is incredibly unusual. That was a high priority for everyone involved in the project, and it makes a huge difference in the show and the stories we could tell.

I was surprised at how much fun the writing was. I thought it was going to be arduous: You give the network some scripts, they give you notes, then we write some more. But these are all very talented and very funny people. It’s 12 professional comedians pitching joke ideas all day. That’s the job. So mostly it was hilarious. A lot of times we’d go through a script joke by joke, asking: “How could this specific line be funnier?”

That process continued after we cast the show and started shooting. Now everything’s different, because now we have the actors, and we can see what lines will play well with a given actor and what won’t. So while we were in production, we were rewriting on an ongoing basis. Millions of drafts of each episode happened.

Did you actively try to recruit writers with disabilities, or did that just happen organically?

From the beginning, it was a priority for me, Apple TV+, and Muse to cast authentically and bring in writers who represent a lot of backgrounds. We wanted to be as diverse as possible, but with a special priority toward people who bring different perspectives with disability.

How did you locate those people?

Finding them was a matter of word of mouth and networking. That’s how most jobs are filled in the entertainment industry, and in most industries, really. We asked people we knew who they knew: “What writers with disabilities do you recommend?” Also, writers have agents, so we’d go to agents and ask, “Who do you have on your roster who has a disability?”

Was everyone on board with the idea that Josh’s limb difference would be a secondary part of his character, as opposed to his central trait?

That’s something I’m obsessed with. Anyone who worked with me on this show probably got annoyed at the amount I talked about this. A lot of it’s just practical. I don’t think those stories [focused on disability] are interesting to able-bodied people, I don’t think they appeal to disabled people, and I don’t think they ultimately achieve the things we want in a social sense, which are, number one, to allow people with disabilities to see themselves on screen, and number two, to allow able-bodied people to be exposed to people with different types of disabilities in a way that might not otherwise happen.

A show that implies that the character is not a total human—that the character is mostly a disability—is not helpful to those goals. I often felt that my main job as a producer and writer was constantly reminding people of that. Obviously, disability is a fascinating part of Josh’s character. This show would certainly not have happened were it not for the fact that this character wears a prosthetic leg. So there is this gravity to it—and by gravity, I don’t mean seriousness, I mean a literal pole we’re drawn toward. But I found myself constantly having to remind other people and myself: “Let’s not get too obsessed with telling prosthetic-leg stories. Let’s remember the other traits that make this character interesting.”

Do you think people with disabilities view themselves differently when they see stories that embrace their whole humanity instead of confining them to the “disability” compartment?

Very much so. I think most people with disabilities have seen enough of themselves portrayed in emotionally manipulative ways. We’ve seen enough people who became villains because they lost their hand, or these inspirational tropes about amputees that we’ve seen on screen repeatedly. To be clear, those don’t offend me. I just don’t see myself in those stories. They put a very low limit on the complexity and realism and humanity of those characters.

If I could have seen someone who looked like me on TV when I was 12, I think that would have been really impactful. A key part of my recovery was meeting well-adjusted hip disarticulation amputees who were 20 years older than me. So seeing a character on TV who’s positive, upbeat, and psychologically well adjusted, who has struggles related to disability but in a realistic and balanced way? I think that those sorts of narratives can be very helpful and even, I daresay, life-changing—especially for young people and adults who have recently lost a limb.

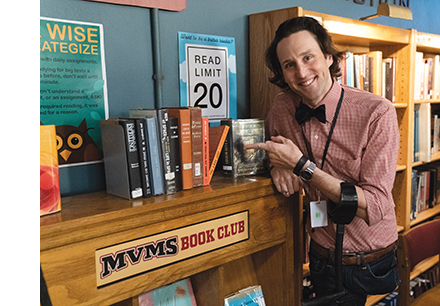

It’s only recently that you’ve started to see characters on TV who have a disability that no one even mentions. They have one arm, and no one talks about how they have one arm—and I think that is amazing. Now you can come in as a person with a disability and play a variety of different types of characters. In Best Foot Forward, I show up in a couple of episodes as Josh’s prosthetist, and my character doesn’t wear a prosthesis. You don’t see that on TV. I’ve never seen that, ever.

In the show, does Josh have Instagram or Facebook? Can he connect with amputees and find community on social media?

That’s a great question. When I lost my leg as a kid, we drove an hour one time to meet this woman who had a hemipelvectomy. She was one of the only high-level amputees we could find, and we only found out about her by asking my doctors, “Do you know anyone else like me?” The fact that people today can find support groups on Facebook, or they can find my Instagram or whatever; that’s amazing. And it’s totally different from when I became an amputee.

In our series, Josh is 12 years old, and our target demographic is eight- to 12-year-olds. So a priority for Apple TV+—and you might think this is ironic for a technology company—was that we don’t want to teach young children to be watching a screen all the time. We didn’t want to portray too much use of social media or cellphones. So Josh ultimately finds his amputee community at his prosthetist’s office. My character obviously has one leg, and the other prosthetist in the office is an actress with a BK amputation. We also have a little girl who is even younger than Josh who’s just lost her leg. He meets this little girl in the prosthetist’s office and realizes he can help her and encourage her. So that’s the support network Josh belongs to.

If Best Foot Forward succeeds, do you feel as if it could open doors for similar shows?

I think more in terms of the potential for individual characters. Maybe writers are more inclined to create an amputee character, or movie directors might cast an actor who has a limb difference to play a character who was not necessarily written as having a disability. In that sense, I think our show can be part of the overall movement toward better representation on screen.

Hopefully it would also create opportunities for people with disabilities behind the camera. We have five amputees in our series on camera, but it’s much easier to find actors with disabilities than it is to find people on the other side of the camera. You can’t go to the Directors Guild or one of the unions and ask, “What electricians do you have with disabilities?” because they don’t know. They don’t keep track of it. There’s not a way to surface these people easily. We had crew members who hadn’t worked for years because they had some sort of disability, and we had people who had never worked because they’d never been able to break into the unions.

We hired [a director with a disability] for two of our episodes, and that meant she was able to join the Directors Guild—and once you’re in the Directors Guild you have access to all the big shows and big movies. We also sought out a limb-different musician to write the theme song for our show. It’s great visibility for the artist, as the song goes on iTunes and plays during our title sequence. The amazingly talented Victoria Canal lent us her songwriting chops and produced a really fresh, cool, catchy tune for us.

Ultimately, more than 20 percent of our cast and crew identified as having a disability, which is very high. One of my proudest moments of the whole season was when an extra [who uses a wheelchair] posted onto her Instagram: “I’ve never been on a show that has so many people with disabilities who are so integrated into the crew and into the cast, and where everything is physically so accessible.” It’s awesome to provide avenues into the entertainment industry for people who might find it hard to break in.

Is that more of an indicator of the show’s success than, say, a traditional measurement like ratings?

I feel hopeful and fairly confident that this show will be very meaningful to families who have a child with some kind of special need. I think they’re gonna feel: This is our life. This tells our story and affirms everything we feel, and we’ve never seen anything like it. I also hope there’s a wider audience of people who find the story universally relatable. Most people don’t have a limb difference, but everyone has some kind of difference, right? Everyone knows what it feels like to feel a little bit different for whatever reason. Hopefully they can see themselves in that aspect of our show.

Best Foot Forward debuts on Apple TV+ on July 22.

The Fame’s Afoot

Despite his success as an author and speaker, Sundquist hardly qualifies as a big-ticket celebrity. “But as a semi-famous person who has a new television show inspired by my childhood,” he says, “I am at risk for becoming at least somewhat more famous.”

He deems it a risk because he suspects that as someone’s fame rises past a certain threshold, their happiness moves in the opposite direction. “So am I on a road whose successful endpoint is going to guarantee my unhappiness?” he asks half-jokingly. “And if so, isn’t this the wrong road?”

Sundquist looks for the answers in his new book, Semi-Famous, which comes out July 19—the same week, by sheer coincidence, that Best Foot Forward drops on Apple TV+. The idea for the book grew out of a poll Sundquist conducted on his social media channels, in which half the respondents expressed a desire to become famous even though 80 percent opined that fame makes a person less happy.

“If you do the math, that means about 30 percent of my followers would rather be famous than happy—or at least, they want to be famous even if it makes them unhappy,” Sundquist muses. “That felt like a phenomenon worth exploring.”

He investigates in his typically breezy style. One chapter tries to pinpoint when, historically, it became possible to get famous, in the sense of being easily recognized by throngs of individuals you’d never met in person. Another posits a unified mathematical formula for fame that lets you compare the relative renown of, say, a 21st-century European football superstar against that of a 16th-century European monarch.

Just in case his TV series catapults him beyond semi-fame, Sundquist says, “I’d like to know: Are there people who are really famous who are also happy? And if so, what’s the secret?” Perhaps he’ll be in a position to divulge that information in his next book.