The results are in from Cybathlon 2024, an international bionics competition that takes place every four years. Races were held over the weekend in Zurich, Switzerland, and other locations around the world. We’ll get to the winners in just a second.

If you’re not familiar with Cybathlon, it showcases the world’s most innovative prosthetic limbs, wheelchairs, exoskeletons, and other assistive technologies. Dozens of engineering teams enter, and each team selects a “pilot” to use the device in the competition. The objective is to complete 10 tasks a quickly as possible; whoever executes the most tasks successfully in the least amount of time wins the trophy.

There are separate competitions in different classes of assistive technology. In addition to arm and leg prostheses, Cybathlon device classes include wheelchairs, robotic assistance, vision assistance, exoskeletons, brain-computer interfaces, and functional electrical stimulation. Get more info at the Cybathlon website.

This winner of this year’s Arm Prosthesis Race was HandsOn, a Chinese team based at Southeast University in Nanjing. Their device combines body-powered and motorized control elements, producing a lightweight prosthesis with fine motor control. Restaurateur Min Xu served as pilot. Second place went to Bionicohand, a French team piloted by 3D-print pioneer Nicolas Huchet. This open-source device has been in continuous development since 2013. Bionicohand recorded the top score during the preliminary round, but a default in the finals on Task #8 (the “Hot Wire” challenge) doomed their title hopes. No American teams entered the race. Get full results (including videos of the races) here.

In the Leg Prosthesis Race, first place went to the Rehab Tech Leg team from the Italian Institute of Technology in Genoa. The winning device, dubbed Omnia, features a hydraulic-electric knee, a high-profile foot to boost energy return, and an ankle with an innovative lead-screw mechanism. Pilot Andrea Modica skis for the Italian Paralympic team. Two Össur devices made the finals, the Pro-Flex Terra and a leg pairing the Power Knee with an experimental ankle. The Pro-Flex Terra aced the preliminaries with a perfect 100 point score, but in the finals pilot Faris Amra defaulted on Tasks #2 (stairs) and #3 (step-over) and ended up third. There were no American teams in the Leg race either. Get full results and race videos here.

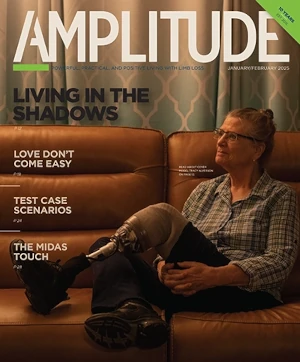

Amplitude wasn’t able to connect any of this year’s Cybathlon participants, so we decided to revisit the first Cybathlon (held in 2016) with Bob Radocy, who piloted his team to victory in the inaugural Arm Prosthesis Race. A lifelong athlete and prosthesis designer, Radocy (pictured above) shared five key reflections about this unique event.

He competed for a Dutch team, not an American one.

“I knew an engineering professor named Dick Plettenberg at Delft University who was getting a team together, and he asked for some input on their design. I told him they didn’t need to develop a new device; a body-powered closing-grip prehensor could probably master all the tasks. A few months later he asked if I would be the team’s pilot. I didn’t really want to, but my wife and daughter both said I should go.”

Radocy’s team was the only one with a body-powered device.

“Everyone else was oriented toward myoelectric hands with advanced controls. One fellow was using an especially high-powered hand; he had battery packs on his back and everything. That type of technology is fine, but don’t call body-powered technology inferior or primitive. I proved that body-powered prostheses were still incredibly viable by beating every electronic hand in the world.”

He was the only competitor to complete all six challenges successfully.

“Everyone else defaulted on one task or another. One of the toughest challenges was to lift an upside-down metal cone that weighed several pounds and move it. It was very difficult to grab onto, even with a normal hand. In another one, you had to maneuver a hoop around an electrified wire that went through various bends. If you touched the wire, you were disqualified. That was quite difficult; it required a wide range of motion and a lot of control.”

The most difficult challenge? Screwing in a light bulb.

“Most electric hands can rotate 360 degrees, so putting in a light bulb wasn’t so daunting—once you triggered the rotation motor, the bulb would screw itself in. I couldn’t do that with a body-powered device, so I developed a technique where I dropped the bulb into the socket and tapped on it very quickly until it caught the lead thread. Then I could spin it in pretty readily. But I never knew how long it was going to take that lead thread to catch. Sometimes it took ten seconds; sometimes it took several minutes. If it took several minutes, it would have blown me out of the competition.”

Radocy’s victory led to changes in Cybathlon’s rules.

“They’ve made it almost impossible to win with a body-powered arm. The light-bulb challenge now has to be screwed into a horizontal socket inside a cabinet, and you can only do that with a rotating wrist. They’ve also added a haptic response challenge, where you have to identify objects based on their shape, without sight. It’s incredibly difficult with a device that doesn’t have a delicate sense of touch. I’d like to see [race organizers] add more tasks that replicate day-to-day activities. But I’m glad they’re challenging manufacturers to continue improving their technology.”