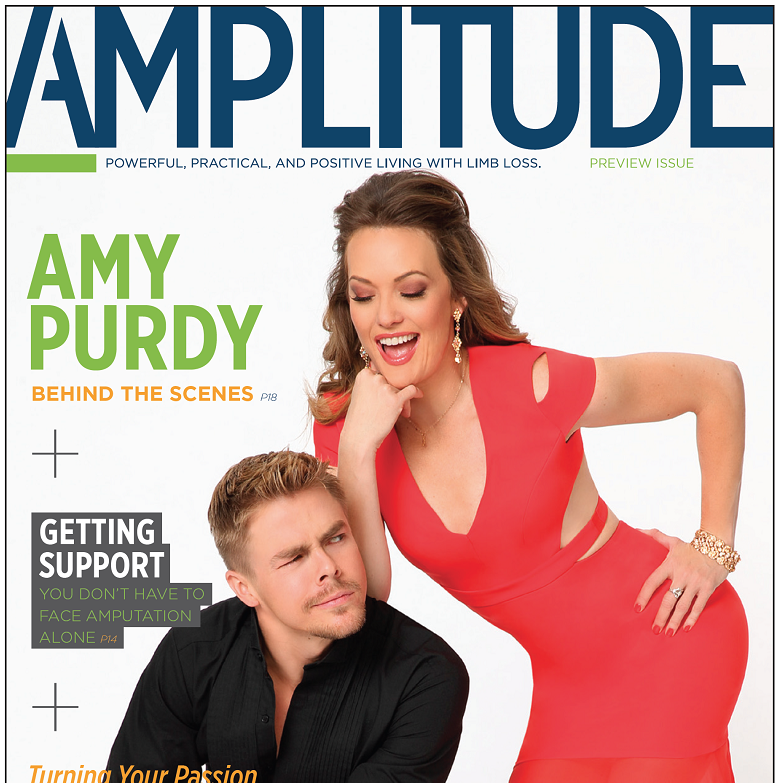

She Shares Thoughtful Advice for Finding Joy and Living Large

Words: Morgan Stanfield

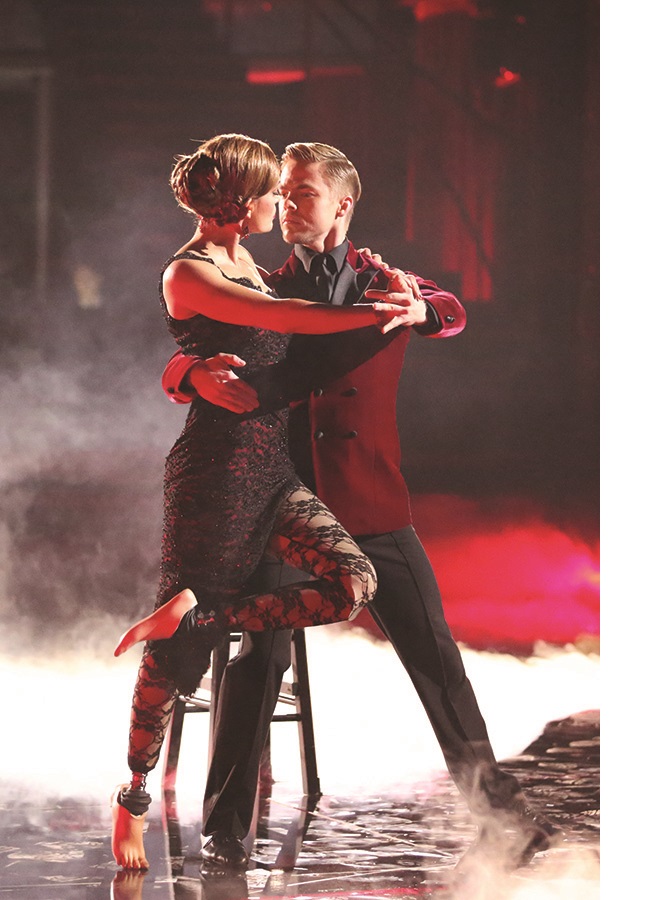

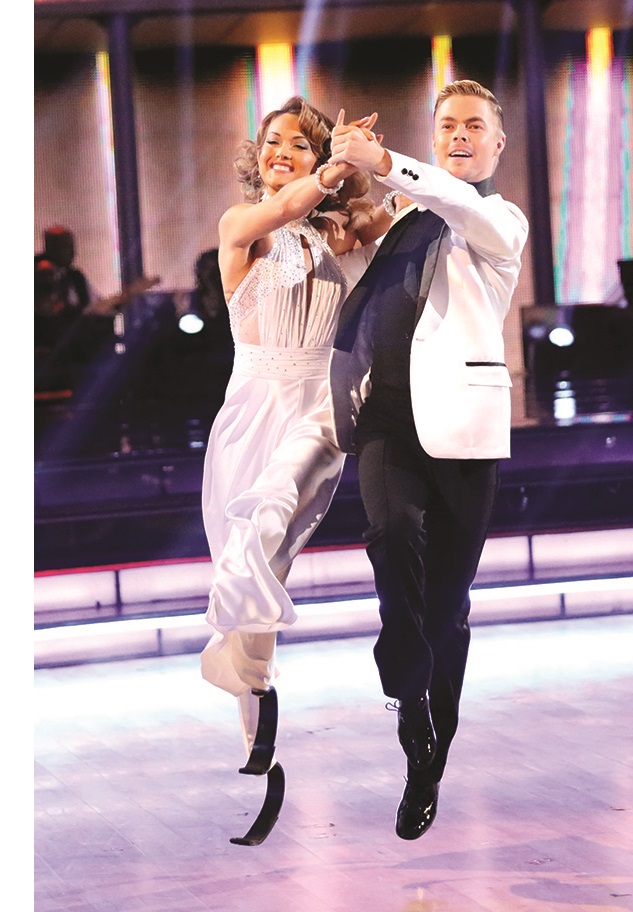

Images: ABC/Craig Sjodin

When Amy Purdy’s glamorous face flashes onto a screen, the biographical montage that inevitably rolls next is a study in contrasts. At 34, the top-ranked snowboarder with old-Hollywood beauty is one of only a handful of celebrities with a major disability. Between starring roles on Dancing with the Stars and The Amazing Race alone, she’s appeared to more than 27 million TV viewers, not to mention a bronze-medal-winning performance at the 2014 Sochi Winter Paralympics and multiple World Cup podium walks. She fronts a line of clothing, has modeled in a Madonna video, has starred in an indie film, and is sponsored by Toyota, Kellogg’s, and Coca-Cola.

But, some bleak facts lie in the background of all this success: Purdy lost both legs below the knees, both kidneys, her spleen, and half her hearing to bacterial meningitis that came within a hair’s breadth of killing her at age 19. She learned to snowboard again seven months later during a time when she was receiving three hours of daily dialysis. She spent her 21st birthday recover-ing from a kidney trans-plant from her father and then has spent much of the time since her illness helping others well outside of any spotlight. Though she garnered much of her mainstream fame on reality TV, she has a pensive, warmhearted intelligence that’s vanishingly rare in such venues. Perhaps most importantly, her biggest accomplishments show a kind of self-discipline that few people ever master. This issue of Amplitude goes behind the scenes with Purdy to learn about the qualities of character that have allowed her to come so far, and the surprising fuel for her achievements: joy.

The Pleasure Principle

Raised in the blast-furnace heat of Las Vegas, Purdy first tried snowboarding at age 15 and says that the sport felt, then, like a key to everything she longed for—freedom, foremost.

Her parents, Sheri and Stefan (who goes by Stef) Purdy, had provided their two daughters with a solid work and self-possession ethic. Sheri was an insurance professional who got up at 4:30 a.m. to work out before going to the office, and Stef managed, at various times, a hotel, a casino, and a rodeo with 500-plus volunteers.

“A lot of parents won’t let their kids speak their minds,” Stef remembers, “but we always wanted to hear their opinions. Of course, if we had a different opinion we let them know about it, but we always let our kids grow into themselves and just helped them move their energy in good directions.”

With that cultivated self-determination, the young Purdy devised and carried out a career plan centered on her passion—she’d work as a massage therapist at ski resorts and then board during her copious time off.

Just months after graduating from high school and obtaining her massage therapist’s license, though, Purdy was stricken down with a strain of bacterial meningitis so deadly that no Nevadan had survived a case of it since the 1970s. As soon as she could understand that she’d lost a part of both her legs, as well as the other devastating effects of the infection, Purdy returned to the one habit she says has been fundamental to all of her successes: visualizing what she loved.

“I was incredibly passionate about snowboarding,” she says, “and as soon as I woke up from my coma, I started daydreaming about how I would do it again. That kept me moving forward and made me think creatively when I hit the boundaries of what I could do. When you’re passionate about something, it doesn’t seem like work, just something that you’re pushing for and excited about every single day.”

Her fantasies seemed thwarted at every turn—by the intense pain of wearing her first prostheses, by her dialysis schedule, and by the hard reality that there were no prosthetic feet designed for snowboarding. For a while, the feet she had mostly sat beside her couch, unworn. Then, one afternoon, Purdy heard “a good song” come on the radio, she recalls. “I wanted to dance. I got up on my legs, grabbed my dad, and had a little dance with him right there. It got me up because it was fun, and that little moment let me decide I could keep going on those legs.” Just seven months later, Purdy was back on her snowy field of dreams, wearing a pair of jerry-rigged snowboarding feet made mostly of duct tape and wood.

Lessons, Hard and Soft

Getting to that point wasn’t easy, Purdy stresses. “With amputation, you’re forced to learn patience, whether you want to or not. New amputees usually don’t realize the process it takes to even get physically, emotionally, and mentally comfortable with a new leg. It took me two years to get ones that fit well enough for me to just do things I wanted to do…. As an amputee, you have to keep in mind that this is what you’re living with now. But when you embrace that and accept it, the world around you will embrace it and accept it as well.”

Sheri Purdy describes how a similar sentiment helped them all live through the hard, early days of Purdy’s recovery. While Sheri and Stef struggled to maneuver vast medical expenses and Purdy’s still-fragile physiology, Sheri also chose to take pleasure in every precious day they had together.

“If it was raining up in the mountains,” Sheri says, “I’d drive us up there to watch the rain. When she could barely eat, if she was craving a chai tea or suddenly thought Olive Garden sounded good, we would just go straight out and get it. And the thing that let us do that so well together was that she allowed me to take care of her. It would’ve been an entirely different situation if she’d resented that I did so much for her.”

Some 34 percent of lower-limb amputees develop clinical depression, and though Purdy’s been fortunate enough to avoid the condition, she did find herself in dark places at times. “It’s so easy to get caught up in your own world, with how hard it is, and how unhappy you are,” she recalls. “The only thing that really helped me in the hardest times was somehow giving back and helping somebody else.”

Helping Others and Staying Focused

In 2002, when she received a grant from the Challenged Athletes Foundation (CAF) to help her compete at adaptive snow-boarding competitions, she found a clear pathway for helping others. She began to volunteer for adaptive sports and prosthetics charities, and in 2005, while building her career in acting and modeling, she and her boyfriend, Daniel Gale, founded Adaptive Action Sports (AAS). A nonprofit focused on X Games-style adaptive sports, especially snowboarding and skate-boarding, AAS has since hosted about 50 events, oftentimes folding them in with mainstream snow-boarding competitions. The organization was also instrumental in bringing adaptive snowboarding to both the Paralympics and the X Games themselves.

One fruit of this labor was the opportunity for Purdy and other AAS-trained snowboarders to earn places on Team USA’s first Paralympic snowboard team in 2014.

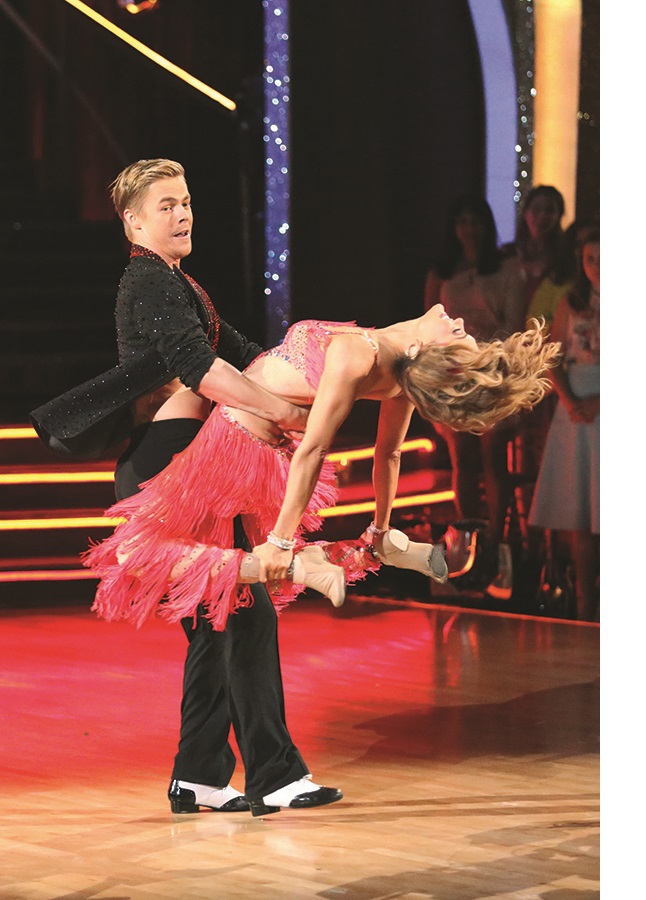

Purdy made the team, but due to a tight schedule and a major opportunity, she had to begin training for her appearance on Dancing with the Stars during her Sochi competition schedule. Her dance partner, Derek Hough, a five-time champion of the mega-hit show, flew to Sochi to begin training with her around her races. Together, they had only a few days of preparation for the show’s first dance, a cha-cha-cha that required astonishingly precise foot-work. The couple tied for third place in the episode, and over the next nine weeks, they consistently scored in the top three, lasting out the entire season and taking second place overall.

Just holding the two vastly demanding schedules of Sochi and Hollywood together required enormous self-discipline.

What made it possible for her, Purdy speculates, was a clever trick of the mind that she learned from her early post-amputation days. “When I was first recovering,” she says, “I was thinking about hearing aids, hearing tests, kidney transplants, going through dialysis every day, and learning to walk again with these new legs. That’s enough to get completely overwhelmed and just shut down. So, I’d think, this week I’m dealing with legs—not hearing aids or kidney transplants or anything else. Next week, I have a nephrology appointment so then I’ll just deal with the kidney transplant. In Sochi, when I was on the mountain snowboarding, I did the same thing—I raced, and I didn’t think about dancing. When I was dancing with Derek, I didn’t think about snowboarding. It was the only way to hold it together.”

This capacity—to do what she loves with steady focus and bulldog tenacity—continues to serve Purdy well. This fall, she’ll be releasing her first book, a memoir, as well as continuing on the joyful work of bringing sports opportunities to children, young adults, and wounded veterans through AAS. When asked for advice for other amputees, she pauses for a long time and says, “Honestly, it sounds clichéd, but I think the biggest limitations are the ones we put on ourselves. I think that as long as we’re focused on our passions—the things that make our hearts beat fast—and we don’t give up when we hit rock bottom, almost anything is possible.”