By Larry Borowsky

Healthcare providers are discovering the benefits of holistic, patient-centered care for amputees. It’s about time.

Dave Crandell was introduced to amputee rehabilitation in the early 1990s, during a nine-month rotation at a Veterans Affairs hospital.

“The director of that program had been a submarine captain prior to being employed at the VA,” recalls Crandell, who was then a resident in physical medicine and rehabilitation. “When you run a submarine, you know what happens? Everyone has to work together, or you don’t come up.”

To stay afloat at the VA clinic, surgeons, prosthetists, pain specialists, and other clinicians coordinated their care for every amputee. It was all hands on deck, all the time—and patients weren’t the only ones served by this approach. Crandell benefited, too. He found it easier to deliver good results for his rehab patients when he could routinely consult with the individuals who had performed the amputation, fitted the prosthesis, prescribed the medication, and managed the occupational therapy.

“If you have all the pieces and everyone’s working together and communicating,” he says, “you have a model system.”

That model has been in place at the VA for decades, but it hasn’t gained much traction in the civilian healthcare system until lately. In 2019, Crandell helped establish the Interdisciplinary Care for Amputees Network (ICAN), one of the nation’s first integrated, full-service amputee clinics outside the VA. Uniting specialists from across the clinical spectrum, the Boston-based center signals a paradigm shift toward a more holistic amputee care model, one that promises to deliver a better experience and better health outcomes for patients.

“People will come to our clinic and say, ‘I’ve been looking for something like this for years,’” says Kyle Eberlin, one of five surgeons affiliated with ICAN. “We think this should be one-stop shopping. Patients don’t only need orthopedic surgeons, they don’t only need plastic surgeons, they don’t only need physiatrists. They need each of us in conjunction, and they need us through the entire continuum of limb care.”

Healthcare professionals are just starting to come around to this idea, but patients are already there. They’re traveling to ICAN from across the United States and even overseas, and that doesn’t surprise Crandell in the least.

“I don’t call it ‘interdisciplinary care,’” he says, summing up ICAN’s appeal. “I just call it better care.”

TRIAL BY FIRE

Crandell didn’t know it back in 1990, but his journey with amputee care was just beginning. By 2013 he’d established a reputation as a national expert on limb-loss recovery and was settling in as director of the amputee clinic at Boston’s world-renowned Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital. That April, as Spaulding was preparing to open a spacious new 132-bed building, two bombs went off near the finish line of the Boston Marathon.

Marilyn Heng, and Santiago Lozano-Calderon.

People with traumatic limb injuries were rushed to hospitals all over the city. Some arrived at the ER with legs already gone. Others faced a difficult choice between amputation or a long, uncertain attempt at limb salvage. Most of the victims had suffered serious injuries in addition to limb loss. The crush of complex cases forced specialists of every type out of their silos, and Crandell’s phone started ringing off the hook.

“It brought the medical community together,” he recalls. “A vascular surgeon from Boston Medical Center who I had never talked to before called me and said, ‘I got three patients.’ The same thing happened at Brigham and Women’s. It happened at Mass General.”

Within days, Spaulding had admitted its first amputee survivor of the marathon bombing. Ultimately, 15 people who lost limbs in the attack came to Crandell’s clinic for in-patient rehabilitation, bearing the sort of wounds you’d normally see on a battlefield. The old VA ethos came to the fore: Work as a team, or we all go down with the ship. Crandell forged a cohesive unit from an unwieldy cast of medical pros, some of whom had rarely encountered limb loss before. Some patients had to be seen by burn therapists. Others needed arduous wound care involving multiple surgeries, debridements, transfusions, and other interventions. Crandell interacted with specialists for hearing loss, infection, speech pathology, and acute stress disorder. Mental health counselors and spiritual advisors came and went daily. And everybody had to work seamlessly with the prosthetists, physical therapists, and occupational therapists who were down in the trenches.

The results of this effort were nothing short of heroic. Not a single amputee died of their wounds. All of the patients who rehabbed at Spaulding—ranging in age from 7 to 71—made successful adaptations to prosthetic limbs and regained their ability to walk. The patients became symbols of Boston’s resilience, while the national media lauded Crandell’s team as miracle workers. Lionsgate Productions shot a big-budget movie (Stronger) about one of Spaulding’s amputee patients and held the premiere at the hospital.

The trial by fire demonstrated what could be achieved with a multifaceted, well-coordinated effort. It deepened the web of relationships in Boston’s limb-care community, giving rise to conversations that might never have taken place otherwise. Ultimately, it brought Crandell together with a cohort of young Mass General surgeons from various specialties—including Eberlin (plastic surgery), Marilyn Heng (trauma), and Santiago Lozano-Calderon (oncology)—over beers one night after work.

Heng and Eberlin had already bonded over their shared interest in limb surgery, particularly nerve-interface techniques such as peripheral nerve stimulation and targeted muscle reinnervation. “We had a lot of patients in common,” says Heng, “and, fortuitously, we both had our main clinic days on Wednesday.” That timing enabled the pair to occasionally consult with one another on knotty cases, which eventually led to a more formal decision to see certain patients as a team. “Kyle had clinic space on Monday,” Heng says, “and I blocked off that time to come to his clinic, and we started booking patients there together.”

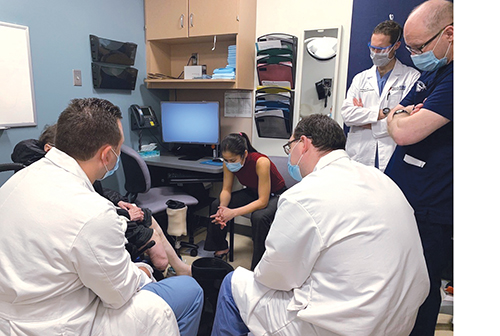

Joe Beall (center) with a patient.

Their unique arrangement became part of the focus during the after-hours conversation with Crandell and Lozano-Calderon. “We sat for a couple of hours, just talking about how we could do this better,” says Crandell. “We really started seriously discussing the idea of working together and how we needed each other.”

That session turned out to be ICAN’s constitutional convention, the birth of a union that now encompasses seven doctors. The occasion seemed momentous enough that Eberlin snapped a photo of the group on his cellphone. “It felt like it was going to be enduring,” Crandell remembers. “Everyone left there saying, ‘Wow, this is something we really need to do.’”

FOCUSED ON THE AMPUTEE

Leigh Ann O’Banion started getting similar ideas in 2016 when she joined Valley Vascular Surgery Associates in Fresno, California. She was fresh off a surgical fellowship at the University of California at San Francisco, where she’d noticed that care teams too often regarded amputation as an unhappy ending, rather than an inflection point.

“Everyone wants to save a limb,” says O’Banion. “We’re all pushing for that. So when you end up with a major amputation, it feels like you failed. Sometimes even the patient can feel that way. But it’s not actually the end. It’s actually the beginning of your new life as an amputee.”

Getting that new life off to a strong start deserved the same energy and attention as limb preservation, O’Banion believed. But when she looked into her clinic’s data, she found it wasn’t happening that way. In the ten years before she arrived at Valley Vascular, patients spent an average of just seven days in the hospital after amputation. Most were sent straight home rather than to a rehab facility. The patients didn’t always attend their follow-up appointments for wound care, physical therapy, and so forth, but nobody was contacting the no-shows to get them back onto the calendar. The bottom line: Only about half of the practice’s patients went on to receive a prosthesis.

“We just weren’t focused on the amputee enough,” O’Banion says. “I thought, ‘There’s got be a way that we can do better.’”

As a starting point, O’Banion convinced a member of the clinic’s nursing team, Jessica Dodson, to become the practice’s amputee care coordinator. Dodson is charged with charting each patient’s progress across the post-surgical road map, using a spreadsheet to check off every prescription, referral, and post-operative procedure. When there’s an empty box in her tracking sheet, Dodson makes sure it gets filled in.

“I had a patient recently who is three months after amputation, and he should have received his prosthesis,” says Dodson. “It didn’t look like he followed through, so I called the prosthetic clinic and asked what’s going on. They told me he’s canceled twice. So then I called the patient and asked, ‘Why are you canceling?’”

In addition to helping patients navigate the post-operative maze, Dodson keeps the dialogue flowing among downstream clinicians to ensure that everyone’s on the same page. For prosthetic care, she refers most patients to two nearby clinics (including a Hanger facility that’s literally across the street), and she’s cultivating a list of go-to partners in other health specialties. The end result is an ad hoc version of ICAN’s interdisciplinary network—dispersed across multiple addresses but serving approximately the same function.

O’Banion described another instance in which a still-healing amputee fell and landed heavily on his surgical scar. He immediately called Dodson on her direct line to ask for guidance; she got a few details about the patient’s condition, had him text a picture of the limb, and then made a referral to ensure he received proper attention.

“He didn’t have to talk to a receptionist and ask for an appointment,” O’Banion says. “He didn’t have to tell his whole story to somebody who doesn’t know him. He called Jess, and she knew exactly what to do and how to help. Every patient who’s just lost a limb—who’s just lost a part of themselves—should have that connection. They need that connection. Having a support system is what’s going to get them from amputation to ambulation.”

BEYOND PROSTHETIC CARE

Unfortunately, says O’Banion, the support system is woefully inadequate for many of her patients. They often start their new lives as amputees burdened with spotty health coverage, unreliable transportation, language barriers, food and housing insecurity, and other challenges.

“Many patients have needs that go well beyond prosthetic care, and that can actually prevent them from realizing the full value of prosthetic care,” says Jonathan Naber, chief program officer for the Range of Motion Project (ROMP). “There are patients who struggle with depression and anxiety, patients who can’t go back to work, patients who can’t access publicly available services. Regaining mobility isn’t just a question of restoring a missing limb. It’s also a question of looking at how they are doing mentally and physically, in their work, in their social life, and with their overall health.”

the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

ROMP operates prosthetic clinics in Guatemala and Ecuador, serving a population with challenges similar to the ones that face O’Banion’s patients. Five years ago, Naber implemented a pilot program based on the World Health Organization’s community-based rehabilitation (CBR) model. Developed in the 1970s as a means of strengthening the safety net for people with disabilities, CBR combines Jessica Dodson’s personalized, high-touch case management with ICAN’s integrated, multidisciplinary clinical care. Each patient receives a series of home visits, spaced at two-week intervals, to address their needs on everything from prosthetic care and rehabilitation to physical exercise, job retraining, mental health, and social reintegration.

Before ROMP gave it a shot, CBR hadn’t been tried extensively in limb-loss patients. But it seemed like an obvious fit, given the huge gaps in amputee care across much of the world. Now Naber has data to back up that hypothesis.

“In every single cohort we’ve done so far, we’ve seen incredible results,” he says. “Average depression scores drop substantially. Same thing with anxiety scores. Quality-of-life scores improve across the board. Physical mobility, and specifically prosthesis use, increases across the board. After several cohorts we realized this was really working, and we started thinking about how to adapt and adjust this to other contexts.”

Last year ROMP brought CBR stateside, piloting the concept with a small group of patients in San Antonio, Texas. Those outcomes, while preliminary, were encouraging enough to merit a more comprehensive trial that’s beginning this spring in Houston. Centered at Baylor University, the project will compare outcomes for two groups of patients: one receiving CBR, the other receiving standard prosthetic care.

“The people in the CBR group will get assessed by not only a prosthetist but also a physician, a physical therapist, and a psychologist,” says Fanny Schultea, a professor in Baylor’s orthotics and prosthetics program. “They also consult with a career coach or vocational rehab specialist. Each of those practitioners writes an individualized treatment plan for that patient. And on top of that, we’ll have a patient navigator to check in every week to see how the people are doing and make sure they’re going to their appointments.”

and Eberlin with PA Jenna Daddario (second from right).

The program is scheduled to wrap up in midsummer, in time for Naber and Schultea to present their data in September to the national conference of the American Orthotics and Prosthetics Association (AOPA), which is helping to fund the study. “I’m assuming we’re going to see better outcomes with the folks who get a more holistic approach,” says Schultea. “But I bet we’ll also find out that it’s actually cheaper to provide care this way. You’re catching things early and preventing secondary and tertiary problems.”

“Having the ability to compare the outcome measures between these two groups is going to be a key moment in the trajectory of CBR,” adds Naber. “Because we can then go to policymakers, financiers, and other decision-makers and show them scientifically valid data about the impact CBR has on people’s lives. Having a war chest of evidence is very important to doing that.”

FILLING THE WAR CHEST

Leigh Ann O’Banion has a nice nugget of data illustrating the benefits of holistic amputee care: Since Valley Vascular installed Dodson as amputee care coordinator, 90 percent of the practice’s limb-loss patients have transitioned to a prosthesis, nearly doubling the previous success rate. O’Banion and two colleagues are now developing a downloadable toolkit that would enable other surgical teams to replicate Valley Vascular’s model and improve their own post-amputation outcomes.

Meanwhile, the ICAN team published a 2021 paper in the journal Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery to educate colleagues about the benefits of the multidisciplinary model. In particular, the paper addressed some of the practical and logistical challenges that have to be solved. “It makes so much sense clinically and for patient care,” says ICAN’s Heng. “But a lot of hospitals have never been set up for this. Every specialty has their own department or division. That can be a barrier in institutions that have done things the same way for years. It requires a huge top-down institutional commitment to make this a priority.”

It’s probably not a coincidence that many of ICAN’s doctors have firsthand exposure to military hospitals, where interdisciplinary care is the rule rather than the exception. Crandell’s epiphany came during his rotation at the VA. Heng treated amputees at a former military hospital (Toronto’s Sunnybrook) during her training. Another prominent ICAN doctor, Ian Valerio, spent five years at Walter Reed and is a naval captain. None of them had to be persuaded that collaborative care benefits both patients and practitioners; they’d already seen it. But many providers, from doctors to prosthetists, will need to be convinced.

“Clinicians are very highly trained and deserve a lot of respect,” says ROMP’s Naber. “But they can fall into this tunnel vision that prevents them from the interdisciplinary communication and collaboration that’s needed to mobilize a patient in a truly multifaceted way.”

The ground may be shifting slowly, but it is shifting. ICAN, Valley Vascular, and CBR offer varying models for how to implement multidisciplinary amputee care in the general healthcare system. And their success is bound to promote broader implementation, O’Banion believes.

“You can’t sit and do things the same way you’ve done them for 30 years,” she says. “That’s not the way we get better. It’s not the way we improve patient care. If you have passion for what you’re doing, you can really make an impact. You can make it feasible for everybody to be afforded the same opportunity to have a good outcome.”