For some amputees, no distance is too great to travel for a prosthetist who makes their life work.

By Melissa Bean Sterzick

Patty Hassett never needed a prosthetist between her teens and her mid-40s.

“I had a prosthetic growing up until just before middle school,” says Hassett, a right below-elbow congenital amputee. “[It was] a hook, but I was more capable without it, and my parents gave up on fighting with me about wearing it.”

She managed well through the early years of adulthood, raising three children as a full-time stay-at-home mom. Hassett did all the messy work of parenting—changing diapers, doing laundry, driving carpool, volunteering at her children’s schools, and caring for her aging parents—as well as the fun things like baking and bicycling with her family. All of it contributed to overuse injuries in her left arm. In 2023, Hassett had to have her left shoulder rebuilt.

“If I knew as a kid that 45 years of overuse is not good on one arm, I would have tried different prosthetics,” she says. “That surgery left me armless. I still have a lot of life to live. I have my kids, and we are very big on family. I want this arm to stay well. That’s what got me into looking at prosthetics more. Now it’s a must, not a maybe.”

The clinic nearest her home on Long Island told Hassett they couldn’t make the kind of prosthesis she needed, so she checked in with the Lucky Fin Project’s online support group for adults. Her fellow amputees pointed her to a Handspring clinic in Middletown, New York, which is about four hours from her home, depending on the traffic.

“It’s going to be a challenge to learn to use a prosthetic, but I know it’s going to be better for my left arm,” she says. “It’s worth the trip. I would travel wherever I needed to for the quality of life.”

Hassett has other orthopedic issues that have required hip and knee replacements, and she broke her femur last year, so long car rides can be tough. The sacrifices are real, but they’re more than worth it to Hassett.

Many amputees and their families have reached the same conclusion. If the right prosthetist or the right prosthesis isn’t available nearby, it can make sense to take on the costs of commuting for care. Getting there might be complicated, and it might add expenses to an already expensive process. But commuting might be worth the extra time and money if it makes important activities—both work and play—possible again.

Hassett and her husband, Joe, make the trip to Middletown and back in a day. Their insurance pays for the prosthesis and the care, but it doesn’t cover gas or lodging if they decide to rest before heading home.

“We couldn’t pay for this out of pocket, so I am lucky and grateful,” Hassett says. “I do feel like you have to have money to do this. I don’t know how accessible it is for everyone out there.”

“He Just Knows”

Debbie Townley has considered getting prosthetic care close to her home in rural south-central Missouri. But the prosthetist who knows her best is based 160 miles away, in suburban St. Louis. That relationship is so valuable to Townley that it far outweighs the money and time she spends going back and forth.

“It’s a long drive, but I just listen to music and head that way,” says Townley, 66. “You couldn’t ask for a better team. It’s worked out well.”

Townley met her clinician, Andrew Sparks, in a St. Louis hospital just before her May 2020 amputation due to lymphedema. Sparks and his colleagues at Orthotic and Prosthetic Lab frequently consult with new clients prior to surgery. “It gives us a chance to ease their mind as to what to expect,” he says. “It’s definitely a huge relief for them to hear that there is life after this amputation.”

For Townley, life after amputation involved relearning to walk, drive, and navigate stairs and uneven surfaces. After she made enough progress to return to her job as a caregiver, she considered switching to a clinic closer to home. But the local prosthetist praised Sparks and told Townley to think carefully before she made a move.

She ended up staying with Sparks, despite the commute. That decision paid off two years ago, when revision surgery left Townley in such severe pain that she couldn’t walk.

“I could hardly take two steps,” she says. “My doctor offered me a nerve block, but I didn’t want to do that. I called Andrew, and he told me to come see him.”

The two-hour-plus drive was a small price to pay for Townley, who was starting to feel desperate over the pain in her leg. “Within 30 minutes, he knew what the problem was, and he knew how to fix it,” she says. “He just knows. Andrew knew I had lost weight. He took the valve off, and he knew what was wrong.”

“You build a relationship with your patients because you’re seeing them so frequently,” Sparks explains. “Half of what we do is talking. You’re the first resource for the mental health side of it, as far as dealing with this big change and working through the process of having an amputation. We’re a place where they can express their concerns.”

That connection easily transcends the physical distance between patient and practitioner. “I can call Andrew in the middle of the day if I have a question, and I get a call back,” Townley says. “I don’t have to wait days.” Sparks adds that he and his team try to address small problems over the phone to reduce travel time.

Townley’s insurance doesn’t reimburse her for travel costs, but the clinic does everything it can to minimize her trips and the time it takes to make adjustments and repairs. For casting a new socket, appointments at O&P Lab start first thing in the morning, and Sparks’ team makes the test socket while Townley waits.

“We are up front with [long-distance patients] when we first meet, because it’s a weekly trip for the first one to two months,” Sparks says. “After that, they’re in their leg and moving on with their life.”

“The doctors think I’m ahead of the game, and I haven’t come across anything so far that I haven’t been able to do,” Townley says. “I owe that to Andrew and Hannah [Portell-Christie, an associate clinician]. They steer me in the right direction. I love going there, and I think it’s well worth the trip.”

The close rapport is meaningful to both the patient and the practitioner. Sparks says, “It’s the biggest compliment I can get from a patient if they are passing several clinics closer to home to get to me for their prosthetics.”

Are We There Yet?

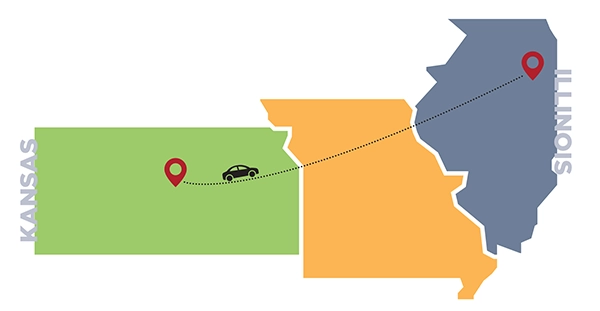

Jim Wittman passes dozens of clinics on the 850-mile trip from his home in central Kansas to his prosthetic clinic in Joliet, Illinois.

Wittman got his first leg at a clinic near home not long after his right below-knee amputation in May 2022. “We knew things would change during the first two years,” he says. “I had the best foot and leg possible starting out, but eventually it was not meeting the level of functionality I wanted.”

A former firefighter, Wittman now owns a mowing business and is nowhere near ready to retire at age 64. In addition to returning to work, he wanted to get back to playing golf, lifting weights, and swimming.

Amputees have as many options for prosthetic clinics as an internet search can find, and that’s how Wittman found David Rotter’s clinic in Joliet. It’s a 12-hour drive in each direction, but the reward for that effort is a custom-made leg that supports Wittman’s active lifestyle on the job, on the greens, and in the gym. He can even wear his new, blade-like prosthetic leg in the water—a feature that will make an upcoming vacation to the Caribbean much better.

Wittman’s more than happy with the finished result. But for Megan Ciotti, long-distance limb care was a necessary, but often difficult, part of her childhood. Now in her early 40s, Ciotti remembers speeding past the trees and snowy fields of rural Pennsylvania during dozens of road trips to see her prosthetist. To fill the time during the two-hour drive between her hometown in Amish country and clinics in Hershey and Philadelphia, Ciotti would get homework done, read a book, or listen to Madonna on her Walkman. But she would rather have spent the time doing gymnastics, running track, marching with the school band, or singing in the choir.

“There was always the promise of ‘we’re almost there,’” she says. “I had a love/hate relationship with my prosthetics. It’s such a process.”

A left below-elbow congenital amputee, Ciotti doesn’t remember getting her first prosthesis—she was just six months old. She got her first myoelectric arm when she was five, and she outgrew her devices almost as often as her shoes all through childhood. Besides trips for casting and fitting, Ciotti and her parents traveled to Hershey twice a year for all-day checkups.

“We’d spend all day there,” she says. “I had to miss school and practices. They would do x-rays and CAT scans and check my spine to see if I had scoliosis. I’ve always had to travel. We need more hospitals that offer services that are more inclusive for everyone.”

Ciotti has had her current prosthesis for several years and doesn’t intend to replace it unless she has to. She wears the device while driving because the state requires it—and, same as ever, Ciotti has to make a long drive from her home in upstate New York to the nearest prosthetic clinic.

It’s a Lifelong Commitment

“I try to tell people who have a new amputation that [limb care] is almost like a marriage,” says Jason Koger, a bilateral upper-limb amputee. “You want to make sure that you want to spend the rest of your life with your prosthetist. This is somebody you’re going to need for a long time, and you want it to be someone who enjoys their work and does a fantastic job.”

Koger, a family farmer who lives in western Kentucky, found his prosthetic soul mate just outside of Dallas, 800 miles away. He’s been making that long commute for more than a decade to work with Rob Dodson of Arm Dynamics.

“I can call Rob any day at any time,” Koger says. “I’ve torn something up and called Rob and said, ‘Hey, I broke an arm and I need it fixed quick.’ I overnight it to him, and he will fix it and overnight it back to me.”

Before he lost both arms in an electrical accident in 2008, Koger had only ever seen one other person with an amputation: his grandfather, Charles Hayden.

“He lost his arm in a corn picker,” Koger explains. “He was 29—and I was 29 [when I lost my arms], too. When I was in the hospital, I literally felt like my grandfather was the first person in the entire world who had lost a hand, and I’m lying there with two gone, and there’s nobody for me to talk to. They’re telling me it’s going to be okay, but everybody in the room has got their hands. Nobody knows what I’m going through.”

Koger’s first prosthetist was geographically convenient, but the devices didn’t fit well—and that was inconvenient, because Koger wanted to stay active and return to farming. He credits his grandfather for that.

“Just seeing my grandad do everything he did—cut tobacco, hang tobacco, drive tractors, everything,” Koger explains. “He had a body-powered hook. I never saw him without it. And he just did everything. He always wanted to be busy.”

Koger stays incredibly busy himself these days. During the 16 years since his accident, he’s traveled the country as a motivational speaker and appeared in Hawaii 5-0, a Matthew McConaughey movie, and a 2014 Apple commercial for the Super Bowl. He spends lots of time with his wife and three children and goes hunting with his crossbow. He’s also written a book titled Handed a Greater Purpose: An Unforgettable Story of Loss and Perseverance.

Koger’s early fears about his future, and the isolation he experienced as an acquired double upper-limb amputee, inform his perspective as an author and speaker. He is adamant that amputees assert their need for functional prosthetic limbs, and he encourages them to shop around for a prosthetist who specializes in the type of device they need.

“I tell people don’t be afraid to travel to the right prosthetist,” he says. “Yes, it costs me more going there than going somewhere local, and it takes more time, but it’s worth it. It’s very important to be fitted right. My first arm was uncomfortable, and I could only wear it for a few hours. We need to be happy and wearing something that is very comfortable. We deserve to be functional and live our lives however we want to live them.”

Melissa Bean Sterzick is a freelance writer and writing tutor. She lives in Los Angeles with her husband and two daughters.

Top image: Seventyfour/stock.adobe.com