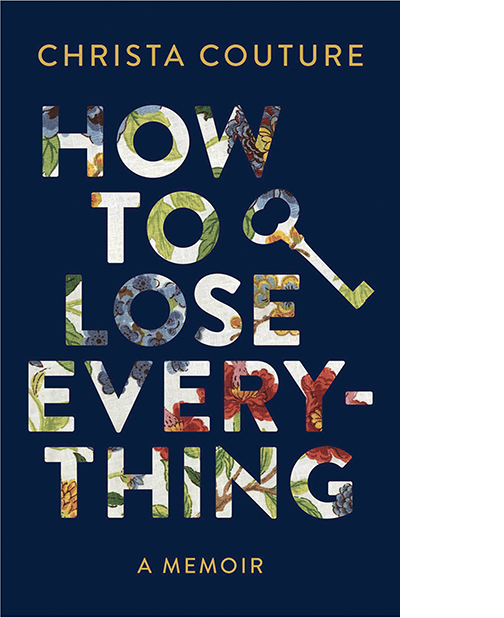

“This isn’t a ‘triumph over adversity’ book,” says Canadian songwriter Christa Couture of her memoir, How to Lose Everything. “It’s also not the sad story you think it is.”

The book isn’t about limb loss per se, but it will resonate with anyone who’s lost a limb, as Couture did to cancer during adolescence. She later lost two sons to health complications, lost her marriage, and got cancer again. But Couture neither wallows in these experiences nor declares victory over them. She embodies them. The resulting narrative feels unpredictable, even though we know the outcomes in advance.

We spoke to Couture in March, a few days after How to Lose Everything’s US release. Learn more about her writing and music at christacouture.com.

What writers have influenced you?

When I decided to write this book, I read a lot of memoirs to get a sense of the [genre]. There’s one called The Boys of My Youth by Jo Ann Beard that really inspired me because she writes such incredible scenes. At one of my writers’ workshops, our facilitator said, “You shouldn’t be able to tell if something is fiction or nonfiction when you’re reading it.” When I read The Boys of My Youth, I said, “Oh, this is what he means.”

One scene in your book portrays people’s discomfort when they learn you lost two children. Have you had similar experiences as an amputee, where the mere fact of your loss creates distance?

As I remembered these moments in my life, what came out was how often I felt like an outsider. Whether it is about motherhood or cancer or being an amputee, I would have to work with that tension of: “What do I say? What impact is it going to have? What assumptions are they making about me?” There’s all this internal labor we do in our thoughts to navigate situations on the fly. There were so many times where I felt different or was made to feel different. I didn’t write the book with that theme in mind, but it’s something that came out.

How do you avoid being defined by loss in a way that makes it impossible to relate to people authentically?

It’s hard. I want to challenge the pitying that can happen—but there also are days that I don’t want to have only one leg. I could never say that on social media, because then you’d have people saying: “I knew it! Having one leg sucks.” But it’s quite tiring to have to maintain one [upbeat] version of the story, when it’s so much more complex. There are things I love about this experience, and I wouldn’t want to change who I am. But some days it really sucks, and you can’t say that out loud.

Where else in our culture do you find compelling portrayals of disability?

You should watch Special on Netflix. Each episode is only about 13 minutes long, so it’s really easy to watch. It’s funny and genuine, and there’s this really funny, moving, authentic sex scene with a disabled person in one episode. I also like Alexis Hillyard’s YouTube series, Stump Kitchen. It’s a cooking show, and she has a [congenital limb difference] that she weaves in. But it’s really about all the normal stuff in life that everyone experiences. That’s what I’m looking for.

That came across in your book. Disability is an essential part of it, but it’s universally relatable.

I hope so. You know, I’m disabled and queer and indigenous, but I just happen to be those things. I wasn’t trying to check off those boxes. It can be so disheartening when people get boiled down to a label, and a lot of assumptions get made about that one thing. We are all more complex than that. I was aiming for a broader experience.