As a freshman in high school, and the first amputee ever to compete in North Carolina prep athletics, Desmond Jackson once got ditched by the team bus en route to a meet. Undeterred, Jackson hitched a ride from a family friend and showed up anyway, an hour’s distance from home. He laced up his spikes and ran.

That tells you all you need to know about this Paralympian’s determination and mental toughness. It also helps explain how Jackson earned a roster spot for the Rio Games at age 16, the youngest male athlete on Team USA. He does not take “no” easily. Just before Rio, Jackson helped his high school team win the state championship—by which time, we presume, the coaches made sure he was on the bus before it departed.

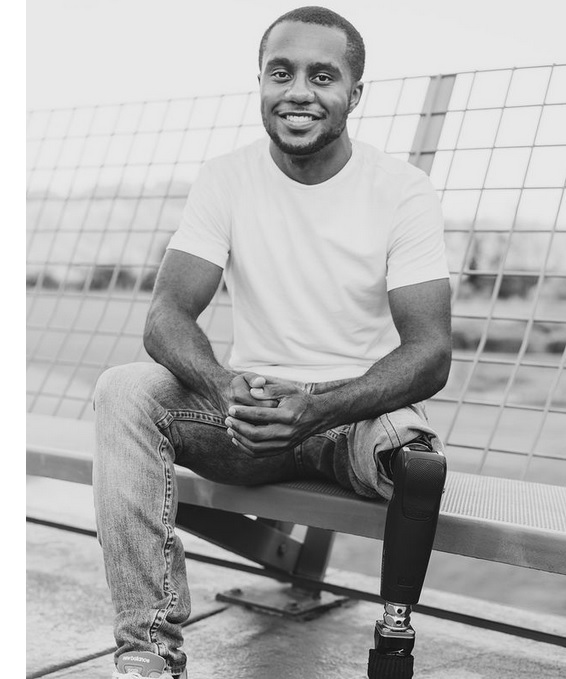

Newly graduated from Campbell University with a degree in sports administration, Jackson is far from finished with breaking cultural barriers and blazing new trails. We spoke with him last week about the hazards of being first, his battle to gain respect as an equal, and how his experience relates to the broader cause of cultural inclusion for amputees, people with disabilities, and people of color. You can find him on Instagram and on the Web at https://desmondjackson.com. Our conversation is edited for clarity and length. Images are courtesy of Desmond Jackson.

Tell me where you are in terms of your training. Is there anything specifically that you’re working on to get ready for the Trials and then for Tokyo?

I’m happy with where I’m at now, but I always feel like there’s room for improvement. Right now I’m working primarily on jumping off the blade. That’s something that I’ve really been working hard at to get to a high level. The takeoff is what I’m really working to fix. Learning to jump off the blade is different. It’s not like a regular foot. So adjusting to how precise you have to be when hitting the board, that’s really a huge part of it. Distributing your weight as you take your penultimate step and then hit the board and try and come off with height and distance, that takes a lot of repetitions. In the long jump, you’re essentially trying to replicate the same approach every time. And of course that’s hard to do as a human.

Is achieving that consistency for every jump just a matter of getting into a mental routine?

It is 100 percent a mental routine. For me that’s a huge part of it, just making sure that I follow my cues on a daily basis, that nothing essentially changes in my practice regimen or in how I prepare. Whether it be my warmup, putting my spikes on, what I’m thinking about while I’m doing that, I’m trying to be laser-focused. That’s what we’re all trying to do, and each athlete is different in that regard. The sooner you can get to that point and hold it, the better your performance.

I’ve learned a lot about the nuances of long-jumping from Ezra Frech, who’s also hoping for a medal in that event. How would you characterize your relationship with him?

We definitely have a friendship. I’m like an older brother or mentor, because I basically went through everything at his age that he’s going through now. It’s funny to see it happening in front of my eyes. I just try to give him words of encouragement and advice whenever he needs it, either on the track or off the track.

What was it like for you to go to the Paralympics as a teenager? I assume you were the youngest athlete, or at least the youngest male athlete, on Team USA in 2016?

Yes sir. I was. It was a lot, taking all of that in. Having had that experience, I feel a lot more confident now going into Tokyo, but going into Rio I was a kid. I still had a lot to learn, and I think the moment at times got a little too big for me. But it was definitely a great experience, something that I’ll hold with me for the rest of my life.

Did you have anyone who you could get encouragement or advice from, similar to how you’re there for Ezra now?

One person was April Holmes, and another was Regas Woods. Everyone on the team was supportive, but I’ve known those two people for years. They know where I’m coming from and where I’m trying to go, and they’ve always been there for me, providing advice as veterans in this sport. It meant a lot.

Did it help at all that, before you went to Rio, you went through the challenges of being the first amputee ever to run track in North Carolina high school sports? From what I’ve read, it was a pretty intense experience.

It was a roller coaster of an experience. Being the first to do it was a big deal. My family and I looked at the role of being a trailblazer as important, because somebody had to do it first. Of course, the person that goes first is maybe not going to have the best experience. At times it was a challenging struggle. But at the end of the day, I wouldn’t do it any differently.

When you say it was a struggle, fill in a few details for me. What made it a struggle?

Well, at first it was earning the respect of my teammates. I would end up going to certain track meets, and I wouldn’t even be on the heat sheets. Or I would end up running, and then they wouldn’t time me or record my times for whatever reason—and with whatever excuses they came up with.

One of my worst experiences was with my first high school team. We had a track meet, and some kind of situation came up to where I ended up being left at the school while they went to the track meet. And it was pretty clear that it was an intentional act.

You’ve got to be kidding me. That is really hard to imagine.

Those were the kinds of thing that would happen between my freshman and my junior year. Once I really started to make noise in the Paralympic world, that kind of changed. I think it did help me earn respect on a high school level. It was a transition from there to better times. By my junior year everything started to go smoothly, and I was competing on a regular basis. I was able to help get a crucial point or two for my high school team that year in order for us to win the state championship. So that was a huge highlight of my high school career.

To me it was a beautiful thing, because when people on my team were able to see me run and jump and beat able-bodied people, it completely changed the way they approached me. Most people don’t have that kind of experience up close with a person with a disability.

When you think back on the experiences you had in North Carolina athletics, of fighting to be recognized as an equal—can a similar thing happen on a bigger scale as the Paralympics get accepted by a bigger audience?

One hundred percent. I definitely believe that. I believe the Paralympics essentially gives the majority of people the opportunity to see what people that they believe are disabled can do. For a lot of people, that is just mind-blowing. It changes their whole perspective of what it means to have a disability.

I want people in the disability community to have an opportunity to be able to be treated fairly in whatever they do. Because I know when I was growing up, there were people who doubted whether I would be able to keep up with other kids. And I didn’t see other amputees or other people with disabilities participating in sports in my state or my city. That might have been discouraging for me, but I was the kind of kid that nothing was going to stop me from what I wanted to do. So that’s one of the things that drove me. That’s a value I hold very dear to me, giving everyone a fair opportunity to participate.

For me, being African-American also plays into it. Inclusivity for people of all races and different physical and mental abilities, that’s who I advocate for.

How do those dots connect? You’ve had the experience of finally being accepted as an equal as an amputee in a mostly able-bodied world. Is there anything you can take from that experience, and apply toward equal acceptance for Black men and women in a white world?

I would say, for one, treat everyone the same, because you never know what people are going through. People seem to be able to carry a lot of different burdens. I’ve seen it in the disability community, but it’s just as true outside it. I went through a lot of adversity, and just knowing that there is a light at the end of the tunnel always motivated me to get back up and keep going, even when times got hard. That’s really what it takes. Even if it’s a slow process, as long as you keep your nose down and keep moving forward, progress will be made. And when you look back at it, you will be able to see it.

That very patient kind of approach to problem-solving or chasing a goal isn’t always an easy sell these days.

I believe in patience. A lot of problems don’t get solved overnight. If I didn’t have patience, I wouldn’t have made it this far in track and field, because there definitely were moments where things weren’t going great and I wasn’t being accepted. Looking back at it, of course, it was all worth it, because it didn’t stay that way. Things turned around.

Was there ever a time when you thought you might run out of patience? Any time where you felt, “I don’t really see a light at the end right now, and I just feel like stopping”?

I never thought about giving up. But I had times of weakness and times where I would cry. And there’s nothing wrong with crying—I’m not saying crying is a weakness. But sometimes it was just hard. Those were hard moments for me. But I always knew, and I always kept in my mind, why I was doing this. And being a trailblazer was one of the key reasons.

Eventually, when I started to focus on the Paralympics, my goals kind of changed, and I think that helped my mindset. I eventually started looking at the high school circuit as just being a way to get practice reps and run meets to see where I’m at. Then I would use that to translate to preparing for the Paralympics.

What specific goals do you have for the Games this year?

I just want to do my best. And to me, my best is essentially breaking world records and winning gold medals. I’m participating in the long jump and the 100 meters, and I really would love to win both. The 100 meters has always been my best event. It’s like my bread-and-butter. That’s something I’ve always worked on. Between the two events, that’s the event I’m least worried about.

I want to say there’s not any pressure, but this is a big year for me in trying to acquire sponsorships and endorsements, because that’s really the next step in my process. In a perfect world, it will be two gold medals and two world records.

Is there anyone internationally who you consider your biggest rival for the gold medals?

I would definitely have to go with Léon Schaefer out of Germany. He’s put up the best official numbers in the long jump to date. On the 100 meter side of things, Léon and another great 100 meter runner, Vinicius Rodrigues out of Brazil—every time I competed against those two guys, it’s been a great performance. I’ve actually competed against Léon since I was 12 or 13 in the juniors. We’ve competed a long time, and it’s funny to look back on it. We were kids back then, and now we’re here competing for medals and sponsorships and all that kind of stuff.

One last question for you: Is your degree in sports management something you could imagine using to advocate for adaptive athletes, athletes of color, or anyone who needs opportunity and isn’t granted the opportunities they deserve?

One thousand percent. That’s my great passion. I plan on doing this for the rest of my life, and that was one of the main driving forces behind my getting the sports management degree. I’m actually starting my MBA in July, so I should acquire that as well. But that is the future for me.