An up-and-coming sport can help amputees reunite with their bodies after limb loss.

Pole dancing long ago migrated from gentlemen’s clubs to rec centers and gyms. In the past decade, this strenuously athletic endeavor—sort of a mashup of ballet, acrobatics, and yoga, performed in midair—has gained respect as an international sport. The most recent world championships attracted 300+ competitors from 40+ countries. Last year pole dancing earned official recognition from the Global Association of International Sports Federations, a key step on the path to Olympic recognition. By the time the Games come to US shores in 2028, pole dancing might be a medal event—and if it is, there likely will be a matching parapole competition in the Paralympics.

While the ranks of limb-different pole dancers are not great, they’re rapidly growing, and here’s why: Many amputees say the sport helped them rediscover joy in their bodies after limb loss. As one puts it: “I have moments daily where I hate my body and its failings, but I can then go to pole and work my body, and it shows me that it’s strong and capable and to not give up on it.”

Here’s a quick introduction to three world champions and one recent amputee who have made pole dancing an integral part of their recovery.

Deb Roach

When she first started performing in 2012, some clueless dude told Roach she had no business pole dancing because “that stuff’s hot, and disability’s not.” She’s been proving him wrong ever since, winning three world championships and becoming a high-profile voice for amputee rights in her native Australia. A congenital AEA, she hit her stride as an aerialist in Great Britain, where she trained with the celebrated (and able-bodied) pole artist Kate Czepulkowski, aka Bendy Kate. Roach quickly earned her own nickname—Debzillah—on account of her monstrous talent and ferocious drive.

“Pole is a vehicle for us to connect our bodies to joy and empowerment,” she says. “It is hugely satisfying and rewarding. We get to experience our bodies in situations where we face challenges and are supported in our quest to conquer them. What our bodies are capable of becomes far more important than how we look.”

Now back in Australia, Roach operates her own studio, World of Pole, which is billed as “an inclusive space for all bodies to learn, grow and be celebrated.” She also teaches able-bodied dance and yoga instructors to work effectively with disabled participants, and she’s an ambassador for the Amputee Association of New South Wales. Watch the championship-winning dance from Roach’s most recent world title in 2018.

Daniela Pecinová

There wasn’t a single dance pole in Marianské Lázně, the remote Czechian spa town where Pecinová grew up. So when she took up the sport after losing her right leg to cancer at age 17, she had to relocate to a larger town an hour away.

In addition to providing a physical and artistic outlet, dancing kept Pecinová connected with her friends (including her hometown bestie, who became a dance teacher). It also insulated her against the occasional rude comment or inappropriate stare. “To do pole dance you need to be sort of an exhibitionist,” she says, “but to do it with a handicap, even more so.”

She immediately clicked with people she met in the Czech Republic’s disability community. “I enjoy the humor because it’s very dark,” Pecinová says. “I never wanted to make a tragedy out of losing my leg. Because I’m from a small town, everyone in the neighborhood knew [about] it immediately, and I didn’t want them to look at me pityingly. I don’t even know why I settled with it so quickly, but I’m glad that I did.”

See Pecinová dance at the 2018 Czech national finals.

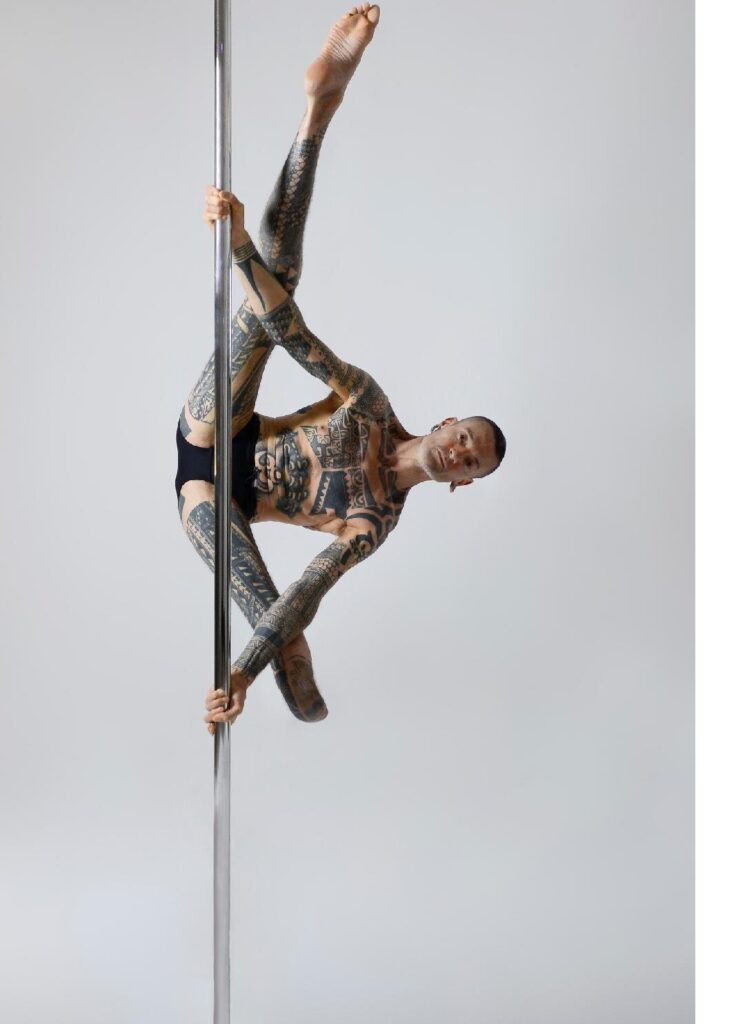

Andrew Gregory

We became aware of Gregory through his Instagram feed last spring, and we included him in our Quarantine Dancers video. Little did we know at that time that he was the reigning world champion in men’s para pole.

His story’s rather incredible. Gregory didn’t take up aerial sports until he was well into his 40s, after more than a decade of limping around on a leg seriously injured in an old motorcycle accident. He started out with a discipline called weightless yoga, until Deb Roach—then a two-time world champ—started teaching at the studio near Gregory’s house. She inspired him to try pole dancing, but as his ability rose, his damaged leg weighed him down both literally and figuratively. In 2018 he decided to amputate. Less than two weeks later he was back on the pole, still sporting the stitches on his residual limb.

“I was so excited the morning of the amputation,” he recalls. “It was like I was reclaiming a part of my body, even though I was in fact losing it.”

Gregory’s subsequent ascent was swift and sure. He won the International Pole Sports Federation world title about 18 months after his amputation. He opened his own studio, began teaching at the London Dance Academy, and started working with the Alternative Limb Project on a pole-friendly prosthetic limb. He even competed against able-bodied pole dancers last February and took first place.

“Pole is a very welcoming sport, and we celebrate all bodies,” says Gregory. “I spend a lot of time in tiny shorts because skin grip is key on the pole, and it’s amazing how wearing so little makes you more comfortable with your body. When people watch me on the pole, the most common reaction is that I’m inspiring, and of course I love to hear that—who wouldn’t? But what I really want is for people to simply think that I’m good.”

We do, Andrew. Here’s his winning routine at the 2019 worlds. You might also enjoy this eight-minute video about Gregory’s journey.

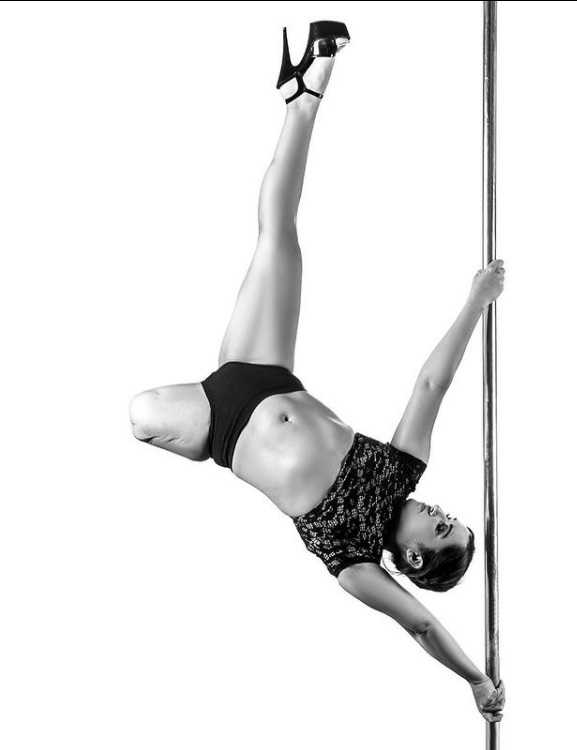

Corinna Snook

Snook isn’t a world champion; not yet anyway. But she’s got the dedication of one, to judge from her Instagram feed. Since losing her left leg to cancer in August 2019, this resident of suburban Sydney has been faithfully documenting her progress, both as an AK amputee and a dancer. The two strands of her journey are completely intertwined; dance is an essential part of her healing.

“One of the things that has kept me going is pole,” she wrote on her first ampuversary. “I pretty much have moments daily where I hate my body and its failings, but I can then go to pole and work my body, and it shows me that it’s strong and capable and to not give up on it.” A couple of weeks later, after a difficult rehab session with her new prosthesis, she added: “It’s crazy that I’m doing these advanced moves in pole yet struggle with the smallest exercises with my leg.”

We can’t tell whether Snook aspires to compete, but that’s almost beside the point—and it’s the main reason we included her here, alongside three trophy winners. She elegantly expresses the true source of the joy that pole dancing can bring amputees. It’s not about winning competitions. It’s about reuniting with your body after limb loss.