Darryl Johnson turned 60 the day before yesterday. But in amputee years, he’s just a kid—Johnson won’t hit his first ampuversary until late July. He’s still getting the hang of living with limb loss, finding new ways to do the things he’s always done. And last month, for the first time since his operation, Johnson got back to doing something he’s done his whole life: heading out on the road to perform.

“Before I left, I was just a nervous wreck,” says Johnson, a soulful vocalist steeped in blues, jazz, and classic R&B. But as he traveled from his home in Detroit to Greensboro, North Carolina, for his appearance at the Carolina Blues Festival, something unexpected happened: Life as an amputee started to feel normal. Comfortable old habits and routines resurfaced. Doubt gave way to self-assurance. The fog of unfamiliarity that Johnson had wrestled with since losing his limb began to dissipate, and he began to feel more and more like himself.

Johnson is grateful to be here at all. With doctor’s appointments hard to come by last summer during the pandemic, Johnson went weeks with untreated circulatory problems. He ended up with an acute infection that claimed his lower right leg and nearly cost him his life. But despite all that, and some unaddressed spinal injuries from a two-year-old car accident, Johnson says he feels better now than he has in years—and his return to traveling and performing is a big reason why.

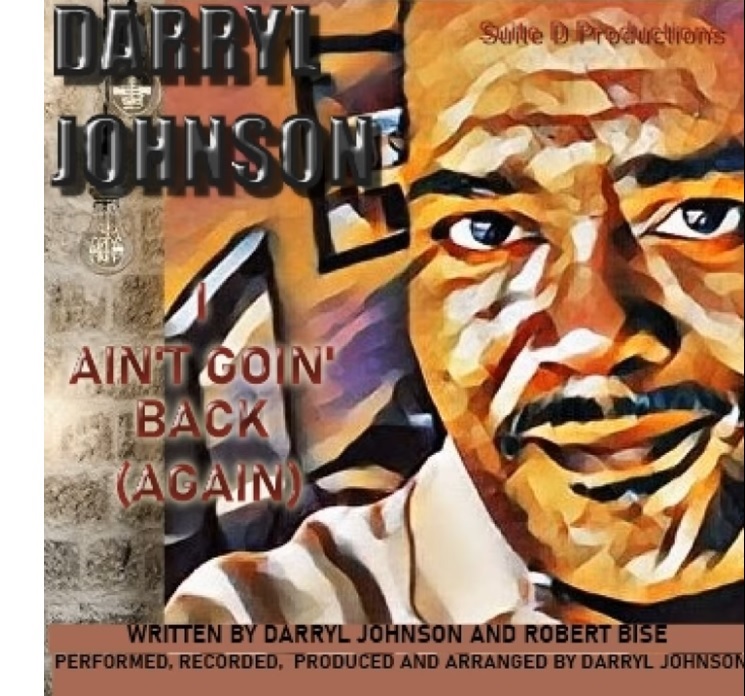

Check out Johnson’s catalog on ReverbNation. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

How did it feel getting back on the road and back on stage as an amputee? Did it meet your expectations?

Well, it started out with driving 11 1/2 hours from Detroit to Lancaster, South Carolina. By the end of it, there was a certain normalcy to being an amputee. I had all but forgotten about my leg by this point, because I’m driving just like normal, I’m getting in and out of the car just like normal. Even just pumping my own gas, or getting out and walking into McDonald’s to order—everything I did brought back just a little more normalcy. A little more Darryl came out with each thing I did, and the more normal I felt.

But it didn’t hit me until I actually got to the hotel and went to take the leg off. There was no walker. There was no wheelchair. Just Darryl and the leg. And that was really, really cool. Had I night been so tired, I might have taken a little time to celebrate.

That was the beginning of what ended up being 12 days of me getting used to being an amputee, as opposed to everybody else getting used to it. Because for all this time, I’ve been more concerned with how it looked and being accepted and people looking at me strange and asking a whole bunch of questions. What I started to realize on this trip is that I don’t have to do anything except be me. The rest of it will take care of itself.

Tell me a little more about that parallel trajectory of you getting used to being an amputee, versus having other people get used to it. What has that felt like?

The first few months were me making sure that everybody else was okay with it. Because I was freaked out, I figured everybody else had to be freaked out too. And being an entertainer, you want your public to like you. So you go all out to make sure everything is as normal as possible. I got everybody else convinced, but then I actually had to convince myself—which is what the trip was for. It was about proving to myself that I could do a normal thing, go on vacation and do a show.

And what about when you got up on stage? Did that feel pretty normal as well?

It was really, really scary to get back on stage. One thing I hadn’t considered was that there are stairs to get onto stage. I’m looking at those and I’m thinking, “I can probably do the rest of this show, but getting up there is going to be an issue.” Fortunately, when it was time to go on, these two huge guys the size of buildings came and got on either side of me and lifted me up on the stage. As soon as I touched the microphone—boom, I was back.

Did it all just come right back? Or did it feel like a little out-of-body at first, and then more natural as you settled in?

There was some apprehension, but any entertainer will tell you that the worst thing you can do on stage is think. Once you think, your mind is no longer on the audience, and it’s no longer on the song. It’s on whatever it is you’re thinking about. A lot of things that I saw as mistakes in the performance, I recognized they happened because I was too much in my head. The Saturday night show was a little better, but during the Friday night show I was concentrating on standing and not falling, and making sure I didn’t trip over whatever was on the floor that I might not have seen or even just tripping over myself. It’s just that whole self-conscious thing. Eventually I stopped thinking and went ahead and did my job. About halfway through the first show I got tired, and when I looked around there was a stool right there. The promoters thought of everything.

I made one other discovery on this trip. I grew up in that area, and I visited my hometown while I was back there. My little sister made a photo album for me because I’m about to turn 60 years old, and it was all these pictures in almost chronological order from my birth right up to present time. And in one of those pictures was our mother, who also was an amputee—right leg, below the knee. The picture was taken in the den of our house, and beside my mother were her wheelchair, her walker, and her leg, which had straps on it. All these memories came flooding back of all the things she went through to put that leg on and how heavy it was. I remember her goal was to walk down the aisle when my sister got married, and she did it.

What I realized in looking at that picture was that all my fear from the past 10 months came from what my mother went through. Because anywhere she went, she either had to have the walker or the wheelchair. It was a big deal even just to go to the grocery store. And here I am, 35 years later and a thousand miles away from home, and all I have to do is stick my stump in and push, and it clicks. I’m being told the leg is supposed to get used to me, I’m not supposed to get used to it. If it hurts, we fix it. But she didn’t have that option. If it hurt, it just had to hurt.

So this trip helped put all those memories behind you?

I didn’t even realize they were there. It isn’t that I had forgotten she was an amputee, but I had moved it to the back of my mind, and it was causing doubt. There was doubt if I’d ever perform again, or if I’d even want to. All of that changed because of this trip. I saw my prosthetist yesterday, and he said he could see a change in my confidence level. I know I can do things now.

Before I left, I was just a nervous wreck. I attended a video support group that was suggested by my physical therapist, and I asked the guys in that group all these questions about traveling: “Do I take the chair and all the socks, the cane, the walker, and anything else I can put my hands on?” That was the whole point behind driving, so I could take everything I needed and have my own car, so I wouldn’t have to worry about transport. The people in the support group said, “Why are you taking that stuff with you?” Because I might need it. “Did you carry wheelchairs and walkers and canes before your amputation?” Well, no, I didn’t need them but I need them now. “And why do you need them now?” Because somebody cut my leg off. “OK, but they gave you another one right?” Yeah. “And you have full function now?” Yeah. “Well then, why do you need all the other crap?”

The words security blanket came to mind, but I wouldn’t say them. I just trusted the group and I left everything behind except the cane. And the cane is the one piece of equipment I never use. So it became a matter of having to figure out how to get along without the quote-unquote crutches. The more I did, the more I realized that all I had to do was the same stuff I had been doing before. A prayer was answered: I asked to be put back to normal. and I was.

So having had this positive experience, what’s the next thing you might try?

I’m really, really excited about skydiving.

No way. That’s so interesting. We’ve written about skydiving for amputees before. Tell me about where that idea came from.

I would have to say God. Skydiving is something I had always been curious about. Everything I’ve read says that. It’s the ultimate way to be at one with you. Because there’s nothing but just you floating there.

And when I woke up after the surgery, the doctor told me that had I not come in when I did, I would have been gone in a few hours. So just to wake up was a miracle, and you do look at life completely differently. It’s like: Okay, He didn’t kill me on July 27, 2020. So I guess He’s not going to kill me when I jump out of an airplane, either. It’s just not going to play out that way. It can’t play out that way. It doesn’t make sense. And from what I’ve been told, He’s not stupid.

Do you have more performances coming up? Are you getting back on stage anytime soon?

There’s nothing anytime soon. I’m going to be out for two months with throat surgery later this year, but I’ll be in the studio recording. I’m doing some in-school programs where you do a few songs in an intimate setting with the kids, and then you answer all their questions and hopefully get some of them to to look at music as a profession.

I’m also thinking about biking and several other things. I’m infinitely healthier now than I was the two years before the amputation. I can’t tell you when I have felt the way I do now. I’m working out three times a week with a physical therapist and just doing things differently overall. At the time of the amputation I learned that I was severely diabetic, so I’ve changed my diet drastically. I’m drinking a lot more water, eating a lot more vegetables and fruits and stuff like that.

The biggest thing—and I’ve talked to some other people who are amputees about this—was coming off sugar. The studies show that sugar activates the same pleasure sensors that cocaine does. That’s why it’s so difficult to get off of it. My sister’s a diabetic too, and she’s taught me a lot. She says: “Don’t look at it as what you can’t have. Look at it as what you can have, and you can have anything you want.”