What do the street protests over George Floyd’s death have to do with limb loss?

No matter the color of an amputee’s skin or the size of their paycheck, the challenges of limb loss are relatively equal from person to person. Nearly all amputees face impacts related to mobility, health care, fitness, pain management, and so on.

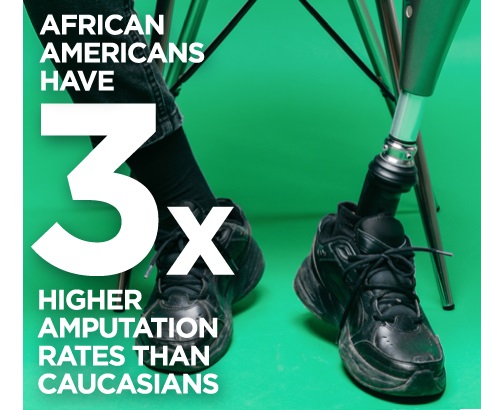

But the causes of amputation aren’t equal. It’s been known for years that, within the United States, amputation is significantly more prevalent among people of color than it is within the general population. The disproportionate rates are related to race-based disparities in care and treatment of diabetes, vascular disease, high blood pressure and other health factors that often lead to limb loss. Low income is also highly correlated with limb loss.

ProPublica tackled this issue last month in a report titled “The Black American Amputation Epidemic,” observing: “[T]he rate of amputations across the country grew by 50 percent between 2009 and 2015. Diabetics undergo 130,000 amputations each year, often in low-income and underinsured neighborhoods. Black patients lose limbs at a rate triple that of others.”

In a week where Americans are wrestling to reconcile national ideals of equality with painful evidence of inequality, it seems essential to recognize that one of the costs of inequality is limb loss. The factors that drive up amputation rates among African Americans arise from the same set of social issues that led to George Floyd’s death.

“I do think there’s a connection,” says Sean Harrison, an African American amputee and founder of the Amp Life Foundation. “I don’t think the protesters are necessarily thinking about this from a medical standpoint, but I would say that’s another dimension of it. When medical companies do studies to try to understand [high rates of amputation among black Americans], what they come back with is the lack of education for taking care of yourself and the lack of overall resources. There are fewer doctors, less access to medicine, less nutritious food available to people in these communities.”

Harrison, who works as an amputee patient advocate for Hanger Clinics in northern and central California, regrets that this week’s protests included some property destruction, which may end up exacerbating the health problems that contribute to limb loss in black and low-income communities.

“It’s a devastating blow when people are destroying things,” he says. “I saw this older lady being interviewed on TV, and she was saying how she can’t get her medicine because of the protests—the store in her neighborhood was looted, the pharmacy was shut down, and she couldn’t get to the bus. There are nurses who can’t get into into these neighborhoods to see patients who need their wound vac dressings changed.”

But Harrison sympathizes with the protestors’ grievances on a very deep and personal level. He grew up in the South during the Civil Rights era and has experienced plenty of discrimination personally. Although he doesn’t talk about it often, he lost his leg when a policeman—mistaking him for a criminal suspect—crashed into him on a San Francisco freeway.

“I could have been one of those young black men who died at the hands of the cops,” Harrison says. “I’ve been through it. I’ve lived it.”

Likewise, most amputees have lived the reality of being discriminated against, subtly or overtly. Maybe you understand the frustration and outright anger that comes with being excluded, overlooked, underestimated, or condescended to. Maybe you can relate to the experience of being prejudged—of being treated as “less-than”—because of your physical appearance.

But you also know the power of healing and the tremendous human capacity for adaptation. That, too, is a reason for every amputee, regardless of skin color, to take an interest in what’s happening this week on the streets of our cities.

What’s your take?

Let us know how you feel about the connections between limb loss and racial inequality. Send email to larry@livingwithamplitude.com, or get involved in the conversation at our Facebook page. We’ll share the most thoughtful responses we receive in a future newsletter.