By Amy Di Leo MS

A summer day a decade ago changed the course of Dustin Maxwell’s life.

“The accident was on July 20, 2008. I was boating with friends when our boat hit a mudslide that threw me off in front of the boat and I was hit by the propeller,” recalls the now 34-year-old. “I lost a lot of blood, and as soon as I stood up out of the water, I knew it was serious—I had deep cuts and broken bones all through my forearms, left shoulder, and left knee. The surgeons and doctors performed a minor miracle in my opinion,” Maxwell says. “They did everything they could to save my forearms and hands, but it wasn’t possible.”

Maxwell, of Covington, Tennessee, a suburb of Memphis, had both arms amputated above the elbows, and doctors put in pins to hold together his upper right arm and knee. Maxwell says he is grateful.

The accident clearly put him on a different path, yet perhaps the one he was meant to take. His life before was very busy, but it no longer included art.

“After the accident, I had nothing but questions about the future: ‘Will I deal with pain or discomfort for the rest of my life? Can I be independent? How could I find a job?’

“For the first year or so, I wasn’t depressed as much as I was disappointed,” he continues. “Doing seemingly easy things would be hard sometimes, which was aggravating. Adapting is hard. The feelings and sensations in my arms were constantly changing too. It wasn’t painful, just worrisome because I didn’t know when or if it would stop.”

A New Life

Some of his questions were answered when he met a business owner in the hospital who also had double upper-limb amputations. Maxwell says meeting him and hearing what he had accomplished was encouraging.

“About a year after the accident, I felt like trying something I could actually physically do and bought some paint, paintbrushes, and canvases, and got started,” he says. “It’s been a long process to get to where I’m at today. I can see constant improvement, and I always push myself. I don’t use an easel because I don’t have a long reach, so I paint on a flat tabletop. It’s a physical toll on my body because I have to use my torso and shoulders more than someone who uses hands to paint, but I look at it as a workout.”

Maxwell’s “workout” is yielding recognition in the local art world.

“I’ve participated in several juried art shows in and around Memphis,” he says. “I won ‘Best Use of Color’ at the Tipton County Art Show in 2017. I was featured in Discover Tipton, a special issue of The Leader, our local newspaper.”

Maxwell also held his own artist’s reception in late 2016 and was featured that year in the Young Collectors Memphis Contemporary Art Fair.

“It always makes me feel good when people walk by and say, ‘You made this? That’s really cool.’ Especially when other artists appreciate it,” he says, adding that the reactions he gets when people see his works have been “phenomenal.”

Artistic Style

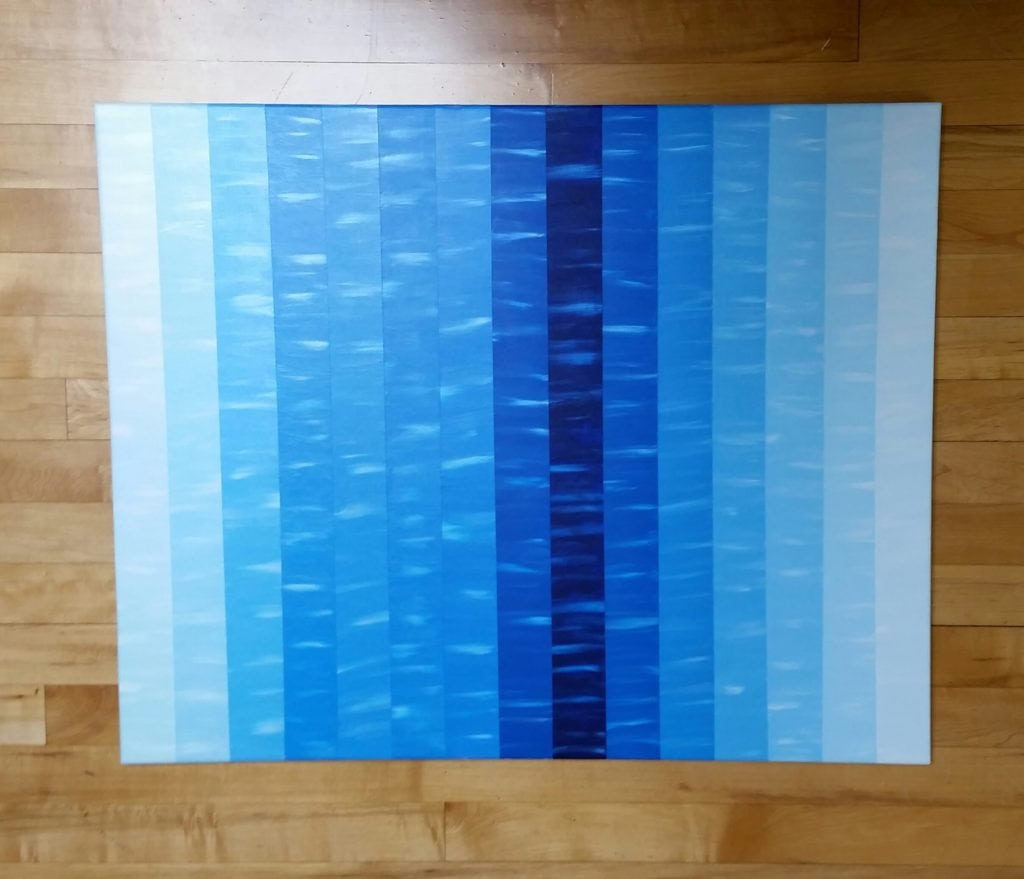

“I’ve had the same style since the beginning—geometric abstraction with street art techniques and influences,” he explains. “I had done a lot of actual indoor house painting before the accident, so I knew how to use tape to make clean straight lines. So I applied that to canvas paintings. It’s kind of become my personal style.”

Maxwell says his technique has evolved and now he can make curved edges too, which he says opens many possibilities in creating wildlife and other non-linear images.

“I like using different mediums and methods to get a new look. Overlapping and layering or using stencils—anything to create something that hasn’t been seen. I like street art, pop art, geometric art, colorful art, weird patterns, and I just combine it all up in the stuff I do. Sometimes I have a basic idea for a painting before I get started, and other times I just make it up as I go. The last few years I’ve been mainly using acrylic and spray paint on canvas or wood.”

And Maxwell does all of this without prostheses.

“Since both of my amputations are above the elbow, it’s really difficult to use prostheses. That elbow joint is hard to replicate smoothly, and it made controlling the prostheses way too difficult,” he says. “As I practiced using my residual limbs, I figured out that sports armbands work best for me and would probably work for most upper-extremity amputees.”

Maxwell slides the band onto his residual limb to hold paintbrushes and pens in place, allowing him to paint, write, and type.

Creating a Future

When Maxwell is not creating art, he’s selling it—in his new minigallery, D Max Art in Munford, Tennessee, and online at www.dmaxart901.com. He says his pain is minimal now and his knee has almost a full range of motion.

“It is definitely frustrating at times, awkward, and uncomfortable too. But pushing through those times builds strength. You’re forced to learn a lot about yourself and keep growing. Seeing what other amputees are doing is helpful because we’re doing almost everything, from athletics and academics to art and science.”

For his part, Maxwell says, “I want other amputees to see me and know that it is possible to do things that maybe you don’t think you can.”