By Elizabeth Bokfi

Clothes mean nothing until someone lives in them.

—Marc Jacobs, American Fashion Designer

Regardless of the type of amputation surgery you’ve had, getting dressed will still be a part of your activities of daily living (ADLs). And whether your choice of clothing is pajamas, jeans, or active wear, the process of how you get dressed will change. With limited range of motion, it might not be so easy anymore to pull on that form-fitting shirt. Or pull up that zipper. Or slide that leg into a pair of skinny jeans. And let’s not forget shoes. If you are a leg amputee, suddenly anything other than flats is off-limits, unle$$ you have a prosthetic foot that’s heel-adjustable. Yes, those were dollar signs, and completely intentional. That’s not even discussing the logistics of getting into certain shoes.

According to the Amputee Coalition, approximately 2 million people in the United States are living with limb loss. With that many people needing apparel, why is finding fashionable adaptive options so difficult? The answer: Fashionable is not always financially feasible. Making things fashionable involves designers. Designers and marketing can eat up a lot of capital. Logistics also drive up cost. Many of the adaptive apparel offerings are sold online and are not necessarily available from domestic sellers, which translates into outrageous shipping fees. Some of them are affordable, and some of them are only affordable to those earning more than just Social Security disability benefits. Many amputees, at some point during their clothing or shoe frustration, dream about making and selling easy-on-the-wallet amputee-friendly items; however, the capital needed to get a start-up clothing manufacturing business off the ground isn’t exactly easy to acquire when you’re only hauling in an average $1,258 in benefits per month.

The clothing we are in should be functional, look good, and make us feel great. Unfortunately for amputees, functionality and fashion are things not always married. There are only so many fit-over-your-socket variations of baggy available out there. It can be especially difficult for women because fashion and beauty are often linked to body image and, ultimately, self-esteem. Some amputees believe the word adaptive perpetuates the stigma associated with disability, further separating the group from inclusivity.

Working hard to change the landscape of adaptive clothing at New York City’s Parsons School of Fashion are the participants of its Open Style Lab (OSL), a nonprofit organization that fuses adaptive with fashion and inclusivity. OSL’s ten-week program focuses on creating fashionable adaptive clothing designs using practical input from models living with a variety of disabilities.

Grace Jun, chief executive officer for OSL and full-time Parsons School of Fashion faculty member, works with people with disabilities in her personal life and in the lab. “I’ve been a designer, probably since college, I guess,” says Jun. Having experienced an injury herself and having witnessed members in her inner circle have surgeries and acquire disabilities through personal injury, Jun is a strong advocate for accessible fashionable clothing.

“I’ve been making something related to adaptive clothing since, maybe, 2014. But I wouldn’t say just clothing because prior to that I worked in technology. I worked on some cell phone and mobile devices that were specifically geared for the aging group, which, naturally, involved user groups or interviews with people with disabilities and those that are aging, in South Korea. I guess it’s just a trajectory of not just adaptive clothes, but ‘What is accessibility?’ in terms of design.”

Christina Mallon, OSL’s chief brand officer, was diagnosed with flail arm syndrome, a form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. Paralysis of her upper limbs makes getting into an everyday item such as a coat challenging. With this in mind, OSL, together with Mallon’s input, designed a stylishly caped coat using built-in garment boning, enabling Mallon to slip it over her head.

Designing functional yet fashionable garments for people with disabilities isn’t Mallon’s only role at OSL. Passionate about inclusivity, Mallon works hard to educate designers about making their products inclusive and accessible in all aspects of the garment industry. For Mallon, it’s not just the garment itself that needs to be accessible, but also the consumer-advertorial experience. At her other job, a global inclusive design and digital accessibility lead role with Wunderman Thompson, a great amount of Mallon’s energy goes into making sure that brands representing disability and inclusion aren’t just paying lip service to consumers. “Making the product accessible and inclusive is one part of the journey,” explains Mallon. “The other part is really making sure that [brands] are creating an accessible experience for consumers with disabilities…. ‘Is the advertising you’re doing around those products inclusive—making sure there are people with disabilities actually in the ad? Are those ads showing people with disabilities in the proper light? Are they making them look like charity?… Is that e-commerce checkout actually accessible with a screen reader?’”

Is there an adaptive clothing line on the horizon for Jun and Mallon? It simply comes down to the basics—money. “We can’t create a line,” says Mallon. “We don’t have the funding.”

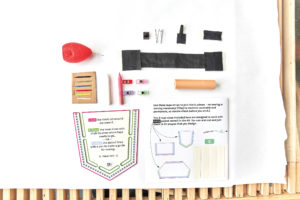

OSL also worked with designers, occupational therapists, engineers, and participants with disabilities to create the Hack-Ability Kit. “These are hacking tool kits that teach you how to hack your own clothing,” says Mallon. “From a sustainability standpoint, when I became disabled, I had so much clothing I had to get rid of because it just didn’t work for me anymore. Buttons and certain other things. So I wanted to figure out a way that people with disabilities don’t have to buy brand new clothes, and also because the unemployment rate is higher for people with disabilities. We know that money is tighter, so we really pivoted to a tool kit practice [lab] rather than an individual garment.”

There’s a market for adaptive wear, and some brands have taken note. In 2016 Tommy Hilfiger tested the waters with its launch of children’s “inclusive” adaptive wear. Hilfiger remodeled items in its existing children’s clothing line by adding features such as magnetic buttons, looped waist adjustments, and adjustable cuffs and ankles. The items were functional, reasonably priced, and looked good. Perhaps most important of all was that kids could feel like they fit in with everyone else.

Partnering with Runway of Dreams, an organization that promotes inclusion in the fashion industry, Hilfiger then went on to release its adult version of inclusive clothing, Tommy Adaptive, in 2018. Features included magnetic button closures on dress shirts, extra-wide neck openings, magnets sewn into fly openings, and for wheelchair users, extra-long shirts and pants with pockets lower down the leg.

Gradually, manufacturers have come out of a deep sleep and discovered there’s a huge adaptive wear market to be cornered. Still a bit groggy though, much of what is available remains utilitarian—think Kohl’s diaper-friendly shirt top, which seems to be much the same as the ones used for babies years ago. (Hey—try adding a ruffled overhang or pocketed flap?) And I’m not sure the American Eagle/Aerie Abilitee ostomy bag cover in hot fuchsia bearing the words HOT S**T is something everyone would want to advertise. We’ll give credit for their unobtrusive insulin pump band.

As promising as it sounds that heavy-hitting brand names are recognizing the need for adaptive options, a significant amount of adaptive apparel ideas—in terms of true adaptive design that doesn’t resemble geriatric clothing—still come about by happenstance through the hacks and solutions of everyday people living with a disability; hence OSL’s Hack-Ability Kit. Hacks, like a lot of stuff, are born out of creative necessity.

Bimla Picot, CEO and founder of Reboundwear, an adaptive wear company in New York, has seen her share of family and friends confront a myriad of health issues, including rotator cuff surgery, double mastectomy, and hip replacement—all affecting range of motion.

“When going through recovery,” says Picot, “each person had to get dressed and undressed…. Instead of being able to reveal just the injury site, each person had to completely remove their tops or bottoms. Dressing my loved ones was a struggle for me as a caregiver, and it pained me to see how difficult and uncomfortable the process was for each person I had to care for.”

In her search, Picot discovered unfashionable adaptive clothing that wasn’t always functional in the way that was needed.

“My 92-year-old friend took great pride in dressing fashionably, and the adaptive clothing I found would have made her feel worse and depressed about her condition. The tops I found would not have been helpful in dressing my friend who had a mastectomy and needed to empty her drains several times a day…. The clothing I saw was made of poor-quality fabric. We made soft, high-tech fabric an essential part of Reboundwear to optimize the wearer’s comfort.”

What is it about the clothing we wear that has such a hold on how we feel about ourselves? Turns out, it’s not just the clothes—language counts too. When it comes to marketing, to some, words do matter.

Zappos presents its Adaption line in a tidy, categorized format that includes gentle titles such as Orthotic Friendly, Seated Wear, and Adaptive Intimates. Excellent, when compared to “elderly adaptive clothing, handicapped, or suffer from .”

“We never use the term disabled,” says Picot. “It’s demoralizing and unfair to assume that millions of diverse individuals with physical challenges all fit into a single category. Your disability does not define you.” Using tag lines such as Fashions for People of all Abilities and Clothing that Adapts to Your Needs, Picot says Reboundwear customers are her best brand ambassadors.

What about footwear for amputees? A good chunk of amputee time is spent on footwear agony—agony over sometimes having to buy a pair of shoes when you only need one, for example. Or footwear that is difficult getting into or out of. (Solution: Check BILLY Footwear.)

In 2015 Nike launched into the adaptive footwear arena in a big way with its FlyEase line. Designed to make entry easier and faster, features include collapsible heels for a more hands-free entry (Air Max 90 FlyEase), zippers and Velcro closures instead of laces (AJ1 FlyEase), and an open and fold-down heel such as the one on the Air Zoom UNVRS FlyEase. Sleek and fashionable, inclusive never looked so sexy.

What’s on the horizon? Coming soon to a closet near you: Zappos’ Single and Different Size Shoes Test (see IF THE SHOE FITS below).

IF THE SHOE FITS

In 2019, after receiving numerous inquiries about selling single shoes or two different-sized shoes, Zappos conducted a research survey that resulted in a pilot project that will focus on a more individually tailored shoe-shopping experience. After taking survey respondents’ input into consideration, the Zappos Single and Different Size Shoes Test features the big guys—New Balance, Nike, BILLY Footwear, Converse, KIZIK, Plae, and Stride Rite. Watch for it walking your way in 2020.

Zappos Single and Different Size Shoes Test

GET INTO IT

This is the part where shoehorn meets every room in the house, every travel bag, and every vehicle in the family. That shoehorn is the Össur Flex-Foot foot shell removal tool. This little number is great for getting into a more difficult hiker-style boot or high-top sneaker. Designed originally for removing prosthetic foot shells, it works great as an everyday shoehorn. Use the long end to get into the boot, and use the short, hooked end for getting out.

Find it at www.amputeestore.com.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

TOP IMAGE: The collapsible heel on Nike’s Air Max 90 makes for a more hands-free entry. Image courtesy of Nike.