When people think about support groups, they often envision people sitting in a circle and sharing their feelings. These days, however, support groups are offered in many formats in addition to traditional, discussion-based groups.

“We all care about having relationships, but we all express and engage in relationships differently,” says Edwin B. Fisher, PhD, who has been a practicing clinical psychologist for more than 40 years. “What works for one person may not work for another. For example, one person may want to meet with others who share similar clinical diagnoses, while someone else prefers to meet with people who share common interests.”

In addition to serving as a professor in the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Fisher is the global director for Peers for Progress, whose mission is to promote peer support around the world. As a result, he knows firsthand how peer support groups can be an extremely powerful tool for improving overall health and well-being. Benefits include:

- MUTUAL SUPPORT through hearing how others have overcome similar challenges, which can provide encouragement and remind participants that they are not alone

- AN OPPORTUNITY to be heard and understood by like-minded people in a safe environment

- A CHANCE to be inspired by other members’ activities—including those that some may not have thought possible

- AN OPPORTUNITY to be social and meet people who have shared interests

A Change in Plans

After losing her left leg at the age of 2, Emily Harvey, Esq., grew up without thinking of her amputation as something she needed to talk about. It’s always just been part of her life.

“My parents framed my amputation as something unique,” says Harvey, 31, whose leg was amputated below the knee as a result of fibular hemimelia and a leg length discrepancy. “So, I never felt like I needed to seek support from peers outside the few weeks I spent at a summer camp for children with limb loss and limb differences.”

It wasn’t until she was working at Walter Reed Army Medical Center (now Walter Reed National Military Medical Center) in 2009 that she began rethinking the importance of being part of a support network. There, she saw hundreds of soldiers receiving care who served in the Middle East and had sustained injuries due to blasts from improvised explosive devices resulting in amputations.

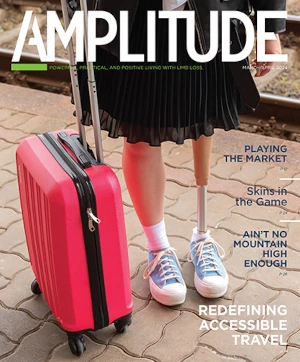

climbing event with LIM359.

“These guys are as tough as they come,” she says. “But I could tell they were getting just as much benefit from being around each other and sharing stories as they were from structured therapy. At the time, I didn’t think much about it, but the seed was planted.”

In 2013, she and her husband moved to Denver, where she met Whitney Harris, a fellow amputee who was completing her prosthetic residency with Harvey’s husband, who is a prosthetist. They quickly became friends and started talking about their experiences growing up with limb loss/difference. Though neither of them had been part of support groups, they discovered they both attended camps for kids with disabilities.

“We got to thinking about how cool it would be to take that concept and morph it into something for all ages that occurred throughout the year instead of just one week each year,” says Harvey, who is now a staff attorney and coordinator of the assistive technology program at Disability Law Colorado. “And that’s when LIM359 was born.”

Together, along with friends Michelle Sydney and Allison Franklin, they created LIM359, a nonprofit, activities-based support group whose mission is to provide opportunities for people with limb loss and/or limb differences to come together to share experiences through participation in group activities.

“We provide a forum for amputees who may not be comfortable attending a discussion-based group,” she says. “I believe both types of groups can provide great benefit to people, and we’re lucky to have a discussion-based support group in the Denver metro area. We’re good resources for each other.”

Since founding LIM359 in June 2013, they’ve continued to hold monthly events with an average attendance of 25 people per event. Harvey says one reason the group has been so successful is because they’ve partnered with adaptive sports organizations that provide equipment and volunteers.

“Being activity-based allows people to form friendships over a good meal or a night of bowling,” says Harvey, who serves as the president of LIM359’s board and oversees its operations. “I love the natural friendships that blossom out of participating in activities together and the confidence people gain when they try something new in a safe environment.”

When she started LIM359, she was so focused on helping others that she never considered how she might benefit from the group. In fact, it wasn’t until the group partnered with the Challenged Athletes Foundation for a swimming clinic that she gained a new perspective.

“I wasn’t excited about swimming that day,” she says. “I was planning on attending, but not participating. Then I realized that, considering we promote trying things outside our comfort zones, I wanted to be a good role model and show people that trying new activities could be fun. Little did I know this clinic would change my life for the better.”

Although Harvey had been cycling and running for several years, the clinic helped her realize not only did she enjoy swimming, but also that she could compete in triathlons if she invested a little time and effort into training. Since then, she completed her first sprint distance triathlon in July 2014 and went on to compete in six more sprint triathlons in 2015, including Paratriathlon Nationals. Under the guidance of coach Mark Sortino of Team MPI, her race calendar this year includes an Olympic distance triathlon, an Ironman 70.3 triathlon, two sprint distance triathlons, and Paratriathlon Nationals. “My triathlon journey is such a huge part of my life now that it’s hard to imagine what I’d be doing with my free time had I not discovered my love of the sport through LIM359,” she says. “If you’re hesitant about seeking support, don’t be afraid or feel like you’re weak if you ask for help. All of us, no matter our life circumstances, need help from others at some point in our lives. By asking for help, you’re also giving someone an opportunity to ask you for help when they need it.”

Just Like Family

Jeff Bourns experienced a variety of emotions growing up as an amputee with each age bringing different experiences and feelings.

“Elementary school was when I first became aware that I was different from everyone else,” says Bourns, whose right leg was amputated below the knee when he was 1 as a result of tibia hemimelia and was further amputated above the knee when he was 9. “It was also when my peers became aware. I felt like the only color Skittle in the package, and I didn’t know anyone like me.”

Junior high was easier emotionally for Bourns because his peers had become accustomed to his amputation. Even though many of his friends saw past him being an amputee, he still wore jeans or a cosmetic cover over his hydraulic knee. By the time he reached high school, though, he became more self-conscious about how he was perceived by women.

“It would have been extremely helpful to have had someone to talk to while I was growing up,” he says. “Talking to my parents about my challenges or the names I was called at school was tough. They did an amazing job raising me as if I were no different than anyone else, but there are just certain things you feel more comfortable sharing with others who can relate.”

When he was 19, he started competing in adaptive track and field events, and—for the first time—met amputees his own age, which he says changed his life.

“Instantly, I felt like I was part of a big family,” he says. “And I wanted to share that experience with other amputees.”

These events inspired him to found the Houston Amputee Society in 2013 with a goal of giving amputees the opportunity to connect in a laid-back environment through casual outings and everyday activities, such as bowling, going to a park, or watching baseball games. In addition to creating a sense of camaraderie and fellowship for amputees, the group also raises awareness about what’s possible as an amputee and provides a safe haven for amputees and their family members, caregivers, and friends to share and learn from one another.

As the group grew in popularity, Bourns began receiving multiple requests for help in creating similar peer groups across the country. As a result, he founded the American Amputee Society in 2014 with hopes of establishing several chapters throughout the United States.

“Being part of the amputee community has helped me grow as an individual,” he says. “Along the way, I’ve had the fortune of meeting so many amazing people, who are now my friends and mentors. I hope that our organizations help forge those same kinds of lifelong relationships for others.”

The Right Fit

When you first join a support group, sharing personal challenges with new people may be difficult. As time goes by, though, trustworthy friendships grow and sharing becomes easier.

“It’s important to understand the power that peer support can have on the human experience,” Fisher says. “Look for peer support services, groups, or activities that meet your needs for engaging with other people. It’s about finding what works best for you.”

For More Information

American Amputee Society and Houston Amputee Society

• www.facebook.com/AmericanAmputeeSociety

• houstonamputee@gmail.com

Edwin B. Fisher

• fishere@email.unc.edu

LIM359

• www.lim359.wordpress.com

Peers for Progress

• www.peersforprogress.org

To locate peer support in your area, visit

• www.amplitude-media.com/Resources/SupportGroups

• www.amputee-coalition.org/support-groups-peer-support/how-to-find-support

• www.empoweringamputees.org

You may also try contacting a local hospital or rehabilitation facility, asking your healthcare providers, searching on the Internet or in your local phone book, or watching for meeting announcements in your local newspaper.