By Amy Di Leo

Planning Is the Groundwork for a Successful Day

Wallet, check. Keys, check. Cell phone, check. It used to be that was all you needed to think about before leaving home for a quick trip to the store—or even for the entire day. But life is different now that you are an amputee. Many things that used to be second nature now present challenges.

Planning is important groundwork, but often when your plan meets the real world, the real world wins. Or as Army Sgt. (Ret.) Joey Bozik, a six-year soldier turned Brazilian jujitsu (BJJ) competitor, notes, “No plan survives first contact.”

Bozik lost both his legs above the knee in 2004 when an improvised explosive device (IED) detonated while he was on patrol in Iraq. He also lost his right arm below the elbow, and his left hand was severely crushed. A lifelong martial arts student, Bozik says, “BJJ has been a great help to me both mentally and physically.”

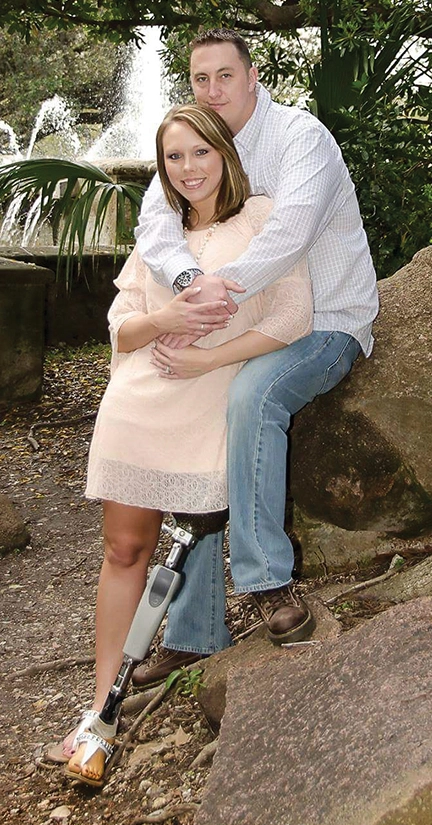

“Losing a leg and living without it is a very hard transition to go through,” says Lindsay Clark of San Antonio. Born with proximal femoral focal deficiency (PFFD), she used a built-up shoe/ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) to compensate for her short femur bone until she was 22. Ten years ago, she chose amputation when the pain in her back, hip, and knee became unbearable. She has no regrets, she says. “It gets easier with time and practice.”

Because amputees expend more energy to ambulate, they also tend to tire more quickly.

“If I expect to walk a lot in the afternoon, I take things slowly in the morning,” says 19-year-old college student Alexandra Capellini, who lost her leg above the knee to cancer when she was 7. “It’s important to know what your standard level of activity is or you may tire yourself out. I give myself extra time to get to class so I can walk at a comfortable pace. I also take into account stairs and hills, both of which can potentially knock my energy.”

Living with limb loss is much easier when you’re in good physical shape as well. Bozik, who takes advantage of that with his martial arts training, created the We Defy Foundation (www.wedefyfoundation.org) to “build confidence for people with disabilities by creating an environment where they train in BJJ with everyone else, not segmented from society.”

Using preventative measures to prepare for a full day of activity can also reduce your risk for discomfort and pain.

Applying a prescription antiperspirant to her residual limb before bed is one trick Clark has learned to help with sweating and shrinkage the next day. Capellini says she does that too and adds that if her prosthetic leg is falling off from shrinkage and sweating during activity, taking it off and cleaning the liner with soap and water helps.

And what about when you’re going somewhere? Sitting in the back seat of a car might be a good option. Being able to stretch out or remove your prosthesis can make you more comfortable and prevent painful pressure sores.

“Since I can’t take off my prosthesis on a plane, I alternate shifting positions, taking walks down the aisle, and going to the bathroom to adjust,” says Capellini, who has traveled to Asia, Europe, and throughout the U.S. by plane.

Clark adds, “I always ask to be seated first. That gives me extra time to get to my seat without feeling rushed. If I take an extra leg with me, I carry it on and store it in the overhead bin. I feel better having it with me.”

“One time, I had forgotten that my knee battery went dead before I got off the plane,” Clark recalls. “I walked down the ramp at a pretty steady speed carrying my extra leg. Before I knew it, I was on the floor and had thrown my leg across the hall into the hands of a stunned pilot. All I could do was laugh, and soon enough everyone else was laughing too.”

Humor and the ability to adjust quickly are essential qualities, especially when children are involved. Clark, who has a 4-year-old daughter, and Bozik, who has a daughter and son, both under 7, understand how kids provide additional insight and entertainment.

“I got married and had both of my children after my injuries,” Bozik says. “They helped to shape a lot of my mentality when it comes to dealing with my disability. For example, shopping with a 3- or 4-year-old who needs a bathroom and having only one hand to deal with the cleanup is the ultimate test of mental stability.”

Figuring out how to maintain your physical stability when navigating snow and ice can also be difficult. Learning to distribute your weight on uneven or unsafe ground becomes an exercise in balance and patience for most lower-limb amputees. Rain presents another issue because computerized limbs could malfunction when wet. Capellini says that wearing long pants and tying a plastic bag around her prosthetic knee protects it.

Though Bozik wears a computerized arm prosthesis every day and has leg prostheses that he sometimes uses, he opts for a motorized power wheelchair day-to-day to minimize the number of prostheses he has to wear.

“Prosthetics are a constant battle,” he says. “They help me drive, lift weights, and cook, but I try to adapt as little as possible. The world is not designed perfectly, and we all face obstacles. It is up to me to find a way to achieve the things I want to do.”

That may mean letting a bus or subway pass instead of running for it, clearing a path from the bed to the bathroom, shutting off computerized limbs when they’re not being used, or carrying extra liners, socks, and a charger.

“Find solutions that work for you and embrace your ability to execute them,” suggests Capellini. “In the end, you’re the one who benefits. If you dare more, you can achieve more.”