One of the most powerful war machines in history actively groomed amputees for its leadership ranks.

By Larry Borowsky

Military historians generally regard the British Royal Navy as one of the most potent instruments of warfare ever assembled. Over several centuries it carried Great Britain’s imperial might across the oceans and around the globe.

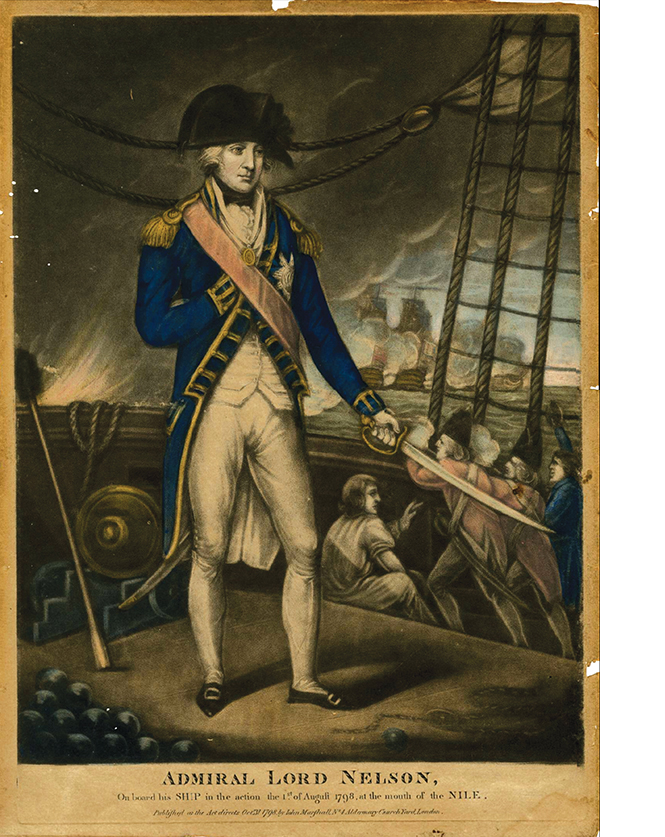

The greatest admiral this fearsome fighting force ever produced—the greatest maritime leader who ever lived, many would say—was Lord Horatio Nelson, who lost his right arm above the elbow in 1797. The exploits that made Nelson one of the UK’s most enduring national heroes occurred subsequent to the loss of his limb, including the 1803 blockade of the English Channel to deter a French invasion and the annihilation of Napoleon’s naval ambitions at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar.

“He made people feel safer, just by the fact that he was out there blowing up enemy ships,” says Teresa Michals, a professor at George Mason University. “The British were under threat of invasion, and people were truly afraid. But Nelson provided this sense of security.”

And he was far from an anomaly. In Lame Captains and Left-Handed Admirals, her forthcoming book, Michals explores how the world’s greatest military force came to rely on dozens of limb-different officers. Far from being marginalized or relegated to desk duty, these figures rose in stature and authority because—not in spite—of limb loss.

“The fact that this ruthless fighting machine needed and valued amputee officers should tell us something,” Michals says. “That wasn’t a historical representation I had ever seen before. I had seen amputees [of that era] portrayed as grotesque, foreign, monstrous. Yet here were these professional men with successful lives, public figures who were perfectly well known and admired.”

Nelson had already attained the rank of rear admiral when his arm was shot off. But most of the officers described in Michals’ book lost their limbs long before they’d started to climb the leadership ladder. These amputees were not promoted out of sheer scarcity—the Royal Navy had more than enough qualified officers who combined impeccable seamanship with the tactical expertise and the commanding presence necessary to succeed in combat. But Michals found that amputees held a surprising advantage within the fierce competition for leadership roles. Instead of being viewed as a disability, limb loss came to be seen as an emblem of supreme ability.

A MARK OF HONOR

In Admiral Nelson’s day (the late 18th and early 19th centuries), naval officers were among the best-known celebrities in Great Britain. Nelson himself was probably the most recognizable person in the country outside of King George III, but other high-ranking officers achieved the kind of fame that, in our own time, is reserved for entertainers, politicians, and athletes. The Royal Navy was the nation’s largest employer, and nearly every community in the island kingdom was bound up, directly or indirectly, in maritime industries. To a large extent, British naval leaders held the fortunes of the whole nation, and every person in it, in their hands.

Trafalgar Square, London,

was erected in 1843.

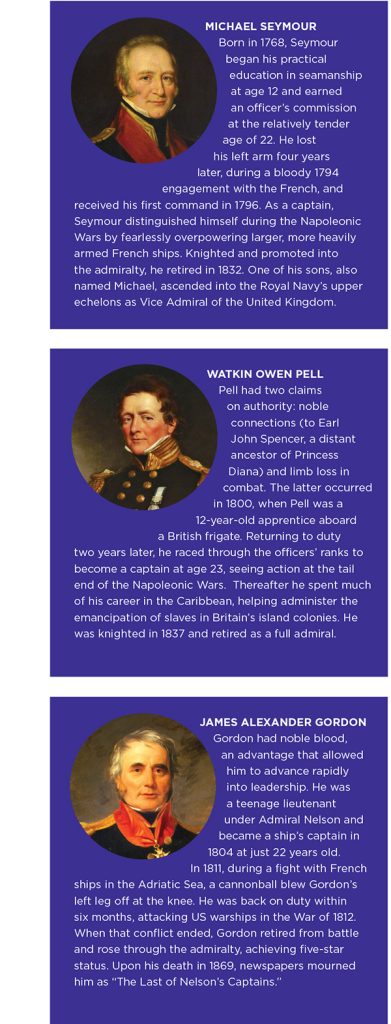

Or hand, as the case may be. Michals identified more than 40 amputees who attained the rank of commander or above. All but four of those officers held subordinate positions when they received their injury. One of them, Sir Watkin Owen Pell, lost his left leg as a rank-and-file seaman during an 1800 battle with a French warship. He was 12 years old at the time. After becoming an amputee, Pell spent another 60 years on active duty, the last 20 or so as an admiral. He was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1837.

Pell’s career nicely illustrates the naval culture that not only permitted, but actively encouraged, the promotion of amputee leaders. Returning to service with a wooden prosthesis two years after his injury, Pell rose to lieutenant and continued to distinguish himself, routinely leading the hazardous invasions of enemy ships. One of those boardings nearly cost him another limb when he sustained multiple bullet wounds in his right arm. In 1810, at age 22, he became a commander, and at age 25 he advanced to ship’s captain.

At no point during Pell’s progression was his limb loss perceived as disabling. On the contrary, says Michals, he easily met the definition of “able seaman” throughout his service. “The phrase ‘able seaman’ meant a certain number of years of service and a certain set of aptitudes,” she notes. “Sailors had specialized skills that took a long time to acquire. Once you had that experience, you were very valuable. It didn’t matter what your body looked like as long as you could do the job.”

Pell could do it all. In addition to fully participating in combat, he performed all the routine duties of ship maintenance and operation. From lugging heavy loads across the decks of heaving vessels to dangling aloft in the heights of the rigging and masts, the one-legged sailor carried out the full range of responsibilities expected of any ship’s mate.

But when it came to competing for high rank, Pell’s limb loss shifted from a neutral factor into an actual advantage. One of his patrons, a senior officer who advocated for Pell’s ascent, provided assurances that “having before lost a leg in the service will give him an additional claim” on authority. In another instance, Admiral Robert Stopford seemed rather pleased to learn that his nephew, Edward, had lost his arm while serving as a junior officer. The injury, he wrote, “will I hope procure him that next [career] step which he is so anxious to get.” Sure enough, the younger Stopford was promoted to captain within a few months.

Then there’s the case of Michael Seymour, an Irish reverend’s son whose career languished for lack of connections among the British nobility. After 15 years’ service he’d only risen to lieutenant, despite receiving sterling recommendations from his superiors. In 1794 he lost his left arm below the elbow in a victorious battle against the French and was advised to “think it an honourable mark instead of a misfortune.” Less than two years later he had command of a 16-gun cruiser, and shortly thereafter he rose to captain. Like Sir Owen Watkin Pell, he eventually made admiral and attained knighthood.

“You could almost think of it as a medal,” Michals observes. “It was truly a mark of honor. I mean, we still say that—we honor our servicemembers on Veteran’s Day, and we say ‘Thank you for your sacrifice’—but [in the Royal Navy] you could actually get ahead by losing a limb. It was only within that relatively narrow slice of society that missing an arm or a leg was seen as a positive thing. But it supports the idea that disability is socially constructed. It’s not the limb difference that’s disabling, it’s society’s unwillingness to accommodate the limb difference. And where I least expected to find it—in this violent institution that offered no legal protections for anyone with a disability—they made accommodations to enable amputees.”

MANAGING PERCEPTIONS

More than two centuries after his death, Lord Nelson remains one of Britain’s most revered heroes. His statue overlooking Trafalgar Square, perched atop a 170-foot-high pillar, is one of London’s most famous landmarks—and Nelson’s limb difference, in sculpted stone as in the flesh, still looms large in his image. The monument depicts his empty right sleeve pinned conspicuously across the front of his coat, just as the admiral wore it whenever he appeared in public or commanded in battle.

Nelson very deliberately chose to exhibit his missing limb as a part of his public identity. He did it in part to proclaim his service to country, much as one might wear a Purple Heart or Silver Star. But it was also, Michals says, an example of how Nelson and other amputee officers shaped their identities and the perceptions of their bodies.

“These men had gotten very good at being looked at,” she notes. “That was their job—to stand there and project confidence while bombs are falling all over and bullets are flying. Being seen in public was an extension of that, so there’s a very conscious act of self-presentation and managing how other people see them.”

In other words, they actively participated in constructing society’s understanding of limb difference, translating the definition that prevailed within the Navy—limb loss as a qualifying, rather than disqualifying, attribute—for mass consumption. This process went beyond the in-your-face exhibition of empty sleeves. Upper-limb amputee Michael Seymour and a fellow admiral, above-knee amputee Sir James Alexander Gordon, had a standard routine they’d enact whenever ceremonial occasions or other events brought them together in front of an audience. An observer described it as “a humorous dispute between those two as to which was the better off, he who had lost an arm or he who had lost a leg—each maintaining his own loss to be the lightest.” As they showered mock pity on one another, the real joke was on any onlooker who truly regarded limb difference as a pitiable state.

At other times they engaged in what contemporary theorists might term “performative able-bodiedness,” overtly demonstrating their competence at routine tasks. When his ship sailed into or out of port—an event that always drew a crowd—Admiral Seymour used to make a show of boarding or disembarking over the ship’s side, ascending or descending the ropes one-armed. In another outward display of physical prowess, Watkin Owen Pell and an amputee officer from a different boat once staged a race up the rigging of a tall ship, showcasing their competitiveness and skill in much the same manner as today’s Paralympians.

But when they lost control of the narrative, these proud officers felt the same mix of frustration and discomfort that 21st-century amputees often feel. During a rare deployment within sight of English shores, Nelson was appalled to find dozens of boats full of gawkers rowing out to see him. “Oh! How I hate to be stared at,” he wrote. “I will not be shewn about like a beast!” Other officers—men who effortlessly kept their footing on slippery wooden planks in rough seas—expressed terror at the prospect of face-planting on the slick marble floors of Buckingham Palace. And Admiral Gordon, an above-knee amputee wearing a rigid wooden prosthesis, was deeply discomfited by his inability to kneel before the king when called to court. His Majesty defused the tension by rising off his throne while Gordon lowered himself into a semi-crouch.

Although such spectacles mattered far less than the substantive work of destroying French and Spanish vessels, they were an unavoidable part of an amputee officer’s burden. These men earned their leadership status on the merits, but their high visibility as emblems of national security obligated them to pair substance with style from time to time.

RECOGNIZED FOR WHO THEY ARE

The amputee officers in Lame Captains and Left-Handed Admirals all served in the Napoleonic Wars, which lasted from ten to 16 years depending on who you ask. “They were long wars,” says Michals. “And the war in Afghanistan was a long war.” It, too, produced a large, visible population of amputee veterans, which in turn raised awareness and influenced perceptions of limb loss across the broader society.

As a university professor, Michaels says she’s encouraged by the increasing presence of diverse populations on campus. “People with disabilities have always been part the community,” she says, “but they haven’t always been vocal about their identity. Today people aren’t keeping quiet, and I think that’s good. They’re much more assertive about shaping perceptions. People don’t want to be accepted ‘in spite of’ a disability. They want to be recognized for who they are. They don’t want to have to be either a tragic figure or an inspiration.”

The Royal Navy’s amputee officers were surely not tragic. And whatever inspiration they provoked rose not from their triumph over adversity but from the depth and breadth of their capacities. That’s an example we can still learn from, Michals believes.

“I think it connects with the KSA framework—knowledge, skills, and abilities,” she says. “Looking at these [naval] careers made me think we should take that seriously. It’s just lazy to label people based on some arbitrary difference and lump them together. The thing that matters is what an individual is interested in and capable of.”

“It’s not just as if people with disabilities became empowered when the Americans with Disabilities Act happened,” she adds. “People with disabilities have been trying things and succeeding at them for a lot longer than we thought.”

More articles about amputee warriors

The Wounded Warriors Who Saved Washington, DC, in the Civil War

Amputee Veterans: In Their Own Words