Upstart prosthetic firms want to provide more amputees with access to devices. But are they moving too quickly?

by Larry Borowsky

In the spring of 2004, a Danish teenager named Lasse Madsen wiped out on his scooter and lost his right leg above the knee. He’d been planning to enroll in a high school gymnastics program later that year, but when Madsen asked how soon he’d be able to return to his sport, his doctor said: “You will learn to walk. You will probably never be able to run.”

Undeterred, Madsen called the school. “I told them, ‘I’m in a wheelchair right now, I only have one leg, but I’m still really interested in doing this program,’” he recalls. School officials said he could attend, but he shouldn’t expect special treatment—he’d be graded on the same scale as his able-bodied classmates. “That was a very important part of my rehabilitation journey,” says Madsen, now 32. “Because that gave me a goal.”

But achieving it with the prosthetic technology of 2004 wasn’t easy. Microprocessor knees and running blades were still fairly new and in limited use; neither was available through Denmark’s health system, which only provided a basic mechanical-knee prosthesis. So while Madsen learned to walk on his everyday device, his prosthetist worked feverishly to improvise a specialized leg that would support enough running, jumping, and flexibility to keep the young gymnast on the mat.

“He found some bits and pieces in the basement,” Madsen explains, “and he put something together.” Before heading off to school, Madsen got a crash course in prosthetic hardware so he would be able to remove his walking leg from his socket, attach his gymnastics blade, and then go back to the regular device after practice. “My prosthetist said, ‘You will be living at this school, and I will not be there with you,’” Madsen recalls. “He showed me what an Allen wrench is, and he showed me: ‘You loosen this screw and tighten that screw, and don’t touch these other screws because that will mess up your alignment.’”

Off he went, a newbie adolescent amputee with a makeshift sports prosthesis. But Madsen didn’t merely survive in his gymnastics program; he thrived. “I did a hundred meets on that foot,” he says. And he learned that by taking an active role in his own prosthetic care, he could get outcomes that established health systems were completely unequipped to deliver.

That’s the core principle for the Levitate blade, Madsen’s uber-accessible running prosthesis. Designed to bridge the chasm between what amputees want and what they’re able to get, the Levitate blade costs just $2,000—a fraction of competitors’ prices. It’s as user-friendly as IKEA furniture, with simple instructions that allow even mechanically challenged amputees to toggle back and forth between their walking foot and running blade. And it’s as easy to acquire as a pair of running shoes from Zappos. Just click “purchase” on your laptop or smartphone, and the product ships straight to your door—no insurance battles, no extra paperwork for your prosthetist, no gatekeepers standing between you and your objective.

Levitate is part of an incipient niche in the prosthetics industry: direct-to-consumer devices. The company joins Unlimited Tomorrow, whose affordable bionic arm has been widely hailed as a model of accessible healthcare, and Open Bionics, a British company whose upper-limb prosthesis is now recognized as a medical device by the US Food and Drug Administration. Although these companies have slightly different models for reaching consumers, all three market themselves to the broad swath of the amputee community that feels underserved, or completely unserved, by the existing system.

“So many amputees have had crappy experiences at one point or another,” says congenital below-elbow amputee Alexis Hillyard, who has an influencer agreement with Unlimited Tomorrow. “They’ve had good experiences too, but everyone has a horror story of advocating for themselves and getting nowhere. So if a direct-to-consumer company allows for better advocacy, I’m all for it.”

There’s ample support for reforming the current system, which excludes too many amputees and leaves too many others dissatisfied. But elbowing the gatekeepers aside can have costs as well as benefits—especially where healthcare is concerned. In April, the Orthotic and Prosthetic (O&P) Alliance issued a buyer-beware statement that read in part: “[We] stand in strong opposition to any direct-to-consumer delivery model for the provision of custom prostheses or orthoses, as it circumvents the necessary, direct working relationship between the patient and an appropriately credentialed O&P clinician….In some instances, direct-to-consumer models may reduce initial costs to consumers, but the short-term cost savings are far outweighed by significant additional safety risks and the long-term costs associated with these models.” (Download the full statement here.)

The solution, argues Madsen, is for prosthetists to embrace direct-to-consumer products as value-adds that increase their own clinical choice and produce happier, healthier patients. “Almost all prosthetists really want to help you find a solution,” he says. “And the standard way of going through insurance is full of barriers for them. Levitate is not trying to take away their expertise. We are helping amputees advocate for their own health and choose what’s best for them.”

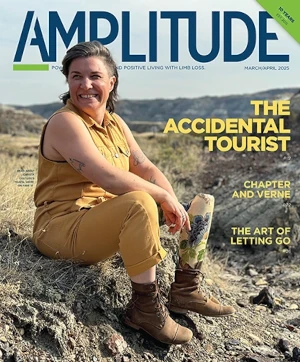

her first 5K race post-amputation

“Your relationship with your prosthetist is a very personal, intimate thing,” says Connie Hanafy. A registered nurse who has worked in pediatrics, cardiology, rehab, and other settings, she knows the essential role of clinical expertise in patient outcomes. But she also has seen how healthcare gatekeepers can prevent clinicians from meeting acceptable care standards.

“I’ve had experiences that make me question if I chose the right profession,” says Hanafy. “Too often, my hands are tied when it comes to getting a patient something they need, and it breaks my heart. When something isn’t covered by insurance, the options just aren’t there. I have tremendous respect for anybody who is trying to provide things that patients would not otherwise have. And that’s why I reached out to Levitate.”

Hanafy opted for below-knee amputation in 2020 after suffering with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) for several years. She’s spent the last two years trying to regain her fitness and burn off weight, but her insurance barely covers basic prosthetic care, let alone a “nonessential” device like a running blade. “They’ll cover my insulin when I gained 50 pounds from lack of mobility,” she says. “But if I want to get more active and get healthy, that’s considered a luxury.”

As a single mom with a limited budget, Hanafy had no hope of obtaining a high-end device costing tens of thousands of dollars. But with a small grant from the Move for Jenn Foundation, she was able to get a Levitate blade. And crucially, her prosthetist—Kevin Towers at Prosthetic Orthotic Solutions International in Marlton, New Jersey—supported her all the way.

That was essential for Hanafy, who’s still unfamiliar with prosthetic technology. “I’ve only been an amputee for a couple of years,” she says, “so I was a little intimidated by the idea of working on my own leg. My prosthetic clinic didn’t know anything about Levitate, but we all sat down and watched the [instructional] videos together, and they said, “‘If this is what you want to do, we fully support you. Bring it in.’”

Kemit-Amon Lewis got similar buy-in from his prosthetist, Brett Rosen of Hanger Clinic in Miami. A marine biologist from the US Virgin Islands, Lewis lost his right leg, right hand, and left fingers and toes to sepsis in 2019. It took multiple rounds of appeals and countless hours of effort to gain approval for a bionic hand—and given the difficulty of acquiring a device that supports daily living activities, Lewis held little hope of getting a sports blade for athletic pursuits.

“I never thought of that as a tool that would be accessible to the everyday person,” he says. “So when I heard about Levitate, I was immediately interested.”

As a recent amputee, and someone who’d lost all ten fingers, Lewis never considered leaving his prosthetist out of the Levitate loop. On the contrary, he asked Rosen to teach him how to adjust the alignment, set the screw tightness, and get the blade on and off unassisted. That collaboration, Lewis says, is just an extension of his routine communication with Rosen.

“It’s always a two-way street,” he says. “Whether it’s pressure points in a check socket, looking at my gait, figuring out alignment, or doing skin care, feedback from the client means the most. And if a prosthetist isn’t explaining it to the point where the patient is comfortable troubleshooting it themselves, they’re doing a disservice to the client.”

customer how to attach the blade

As a scientist, Lewis understands why prosthetists are wary of products that offer simple-sounding solutions to complex challenges such as limb care. “But as an amputee, I know nobody would ever do something to cause themselves harm,” he says. “Prosthetists have to trust their patients. I would never buy a product and not involve Brett in the process. But I appreciate having the option to buy something on my own, especially since insurance doesn’t cover it.”

Jordan Beckwith, better known as Footless Jo to her vast YouTube audience, was initially skeptical of Levitate. “I think prosthetists have some legitimate concerns,” she says. “They don’t want to see anyone hurt themselves, and there are definitely some risk factors.” The biggest potential hazard lies in the unsupervised modification of finely calibrated prosthetic devices. “It’s very frightening to take ownership of that,” says Beckwith. “I rely on my leg every day, so the idea that I’m gonna tinker around with it—I absolutely didn’t feel equipped to deal with that.”

But Levitate met a specific need for Beckwith: She wanted to run her first 5K race since injuring her leg as a teenager. That deep desire outweighed her anxiety about her lack of DIY device skills. In a Footless Jo episode titled “Building a New Running Blade (I Can’t Believe This Worked!),” she attempted to install the Levitate blade on her everyday socket, adjust the height and alignment, test it out with some jogging, and then get her walking leg reattached. To her own great surprise and delight, she pulled it off.

“Figuring out how my leg works and not being scared of it—that was life-changing for me,” says Beckwith, who now has an influencer agreement with Levitate. “The amount of empowerment it gives you is so worth it. It gave me the sense that my leg doesn’t belong to someone else—it’s a part of my body. That was really powerful.”

The experience ended up deepening her relationship with her prosthetist, Beckwith adds. “Understanding how my walking ankle and my running blade are connected to me was very important, because it broke down some barriers around the prosthesis being something outside of me,” she says. “But having the input of a prosthetist who knows so much more than I do is also incredibly important. So it opens up this collaboration. I think that’s a fantastic model to have.”

No prosthetics company has generated more discussion about the direct-to-consumer model than Unlimited Tomorrow. Its 3D-printed bionic arm, the True Limb, sells for $8,000—one-third to one-tenth the price of industry-standard myoelectric devices. The company has won a passel of design competitions, generated reams of favorable press, and landed partnership deals with Microsoft, Hewlett Packard, and other tech-industry giants. Its charismatic founder, 25-year-old Easton LaChappelle, has drawn comparisons to Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg. And the company’s embrace of technological innovation to achieve greater affordability, access, and function is held out as a new paradigm that should be replicated throughout the healthcare system.

Nobody in the O&P profession opposes Unlimited Tomorrow’s ideals. But some question whether the company can actually deliver on its promise.

“I would like to know what their outcomes are,” says Jeff Erenstone, a certified prosthetist with Mountain Orthotic and Prosthetic Services in Lake Placid, New York. “Where’s the research? Who’s reviewed it? Where’s it been published? You can’t just say you’re going to do these things. You need to produce evidence.”

Erenstone is all too familiar with the current system’s headaches and heartaches, so he understands why a simple, streamlined direct-to-consumer process appeals to amputees. “I pay a consultant to help me through the insurance authorization process because it’s so complex,” he says. “So I definitely feel people’s pain. But the reason these devices are so expensive is because they’re very complex. And with that level of complexity, you need a professional who understands them inside and out and understands the follow-up care.”

Julie Alley, president of biodesigns, a California clinic specializing in upper-limb socket interfaces, notes another pitfall of the direct-to-consumer model. “If you’re getting stuff direct to the patient that’s much cheaper, what could happen down the line is insurers could say, ‘That’s good enough for a basic prosthesis,’ and that’s all they will cover,” she says. “And since prosthetists aren’t involved, nobody’s tracking outcomes or looking at functional improvement, so it will be even harder to get coverage for people who need more advanced technology. You want people without insurance to have access to a prosthesis, but you don’t want the market flooded with ‘good-enough’ products, because now people are even less able to get the technology they really need.”

But people already can’t get the technology they need, LaChappelle counters—either because they’re priced out of the market entirely, or because the devices they’re able to get are too limited, uncomfortable, or difficult to master. As many as 40 percent of upper-limb amputees who do receive a prosthesis end up rejecting it, according to studies. If that weren’t the case, says LaChappelle, there wouldn’t be any demand for products like the True Limb.

“A lot of the people who are buying from us have exhausted their insurance options,” he says. “Maybe they don’t have insurance. Maybe they’re just looking for a solution that works better for them. We’re providing an option to people who have fallen through the cracks.”

Whether that option produces better patient outcomes than the current system remains to be seen. Unlimited Tomorrow hasn’t published any figures about user satisfaction and acceptance rates, but LaChappelle says the company surveys its customers constantly and responds swiftly to feedback.

“We’ve collected a tremendous amount of data,” he says. “Our North Star metric is whether we’re producing something that people actually wear. That’s something we’re always closely monitoring, doing our due diligence, and making sure we are producing a product that people are happy with and getting some utility from, whether that’s functional or psychosocial.” Although the company’s research is proprietary, LaChappelle did share that 100 percent of respondents in a recent survey rated the True Limb as durable and pain-free. He also notes that no customer in Unlimited Tomorrow’s database has ever sustained skin damage, nerve damage, or any other residual-limb injury from their product.

Those results are hardly definitive, Erenstone argues. Until True Limb passes muster on the same rigorous scientific standards that other devices are required to meet, he thinks amputees should proceed with caution. “They’ve made a whole lot of promises, but where are the patient outcomes?” he asks. “Where’s the study? A prosthesis, by definition, is a medical device. And they’re delivering that directly to patients without any medical care.”

But if a prosthesis is truly defined as a medical device, Lasse Madsen asks, why does the healthcare system so often contradict its own formulation?

“Insurance companies treat a running blade as sports equipment, so they don’t reimburse it,” he says. “You can’t have the prosthetist and the manufacturer saying this is medical equipment, but the insurers saying it isn’t medically necessary and therefore it isn’t covered. It’s got to be one or the other.”

Erenstone doesn’t dispute the point with regard to Levitate’s product. “I don’t have any problem with someone going online and buying a sports device that’s clearly designated as a sports device,” he says. “But a complete prosthesis, socket included? That is by definition a medical device, and it shouldn’t be provided directly to patients in the absence of medical care.”

That distinction, whatever its merits, isn’t particularly relevant to amputees who can’t acquire the solution they want—be it a bionic arm, a running blade, a microprocessor knee, or anything else. Patients’ overriding concern is to have greater control over their quality of life, and prosthetists have a shared interest in facilitating that. Both parties would benefit from a care model that increases amputees’ options and gives clinicians more ways to apply their expertise. Both want greater ownership over outcomes and less interference from insurance gatekeepers. If new delivery channels help to move that transition along, will heads really explode?

“There are going to be some prosthetists who welcome this with open arms and integrate it into their practice,” Hillyard predicts. “It puts the focus on the consumer and what’s going to benefit them—and that should be the focus, right? Why else do prosthetists do what they do?”

“I got into this field to help people,” says Rosen. “I’ve always prided myself on providing access, and this model gives patients viable access to something that’s going to benefit them. That’s a win for me as well. And it’s not really replacing anything that we’re doing. If anything, it actually makes us more involved in the patient’s care. I think it’s a win for everybody.”

Open Bionics’ model may point the way forward. While the company sells directly to consumers, it partners with certified prosthetists for fitting, alignment, and ongoing care. Rosen believes this approach feels comfortable to Gen X and Millennial clinicians, so-called “digital natives” who are accustomed to curating their own shopping experiences in consumer goods, entertainment, travel, news media, and even dating. As younger prosthetists rise in the profession while more seasoned practitioners age out—and as more companies enter the direct-to-consumer market—the model may gradually gain broad acceptance, Rosen thinks.

Alley, too, thinks direct-to-consumer devices have the potential to drive positive change—as long as their benefits are borne out in the data. “We as an industry have to admit that our results are not ideal,” she says. “We have to get better outcomes and better acceptance rates, and that may mean moving more quickly and innovating as new things come out. Things are moving at light speed. We need to keep up.”