In her debut article for Amplitude, “The Single Life on a Single Leg,” Diana Theobald sums up dating and relationships in a single phrase: “Relying on other people is scary.” That’s true for everyone, whether able-bodied or disabled. “Becoming disabled only heightens that feeling of vulnerability,” she adds—but it also heightens the sense of clarity about who’ll be there for you when you really need them, and who might not.

Witness the Valentine’s Day “date” Theobald had last year with a new-ish beau, who dropped everything to rush Theobald to the emergency room at 5 a.m. after she gashed her residual limb in a fall. He hung out in the lobby all morning while they checked her out and stitched her up, then drove her home and bought her breakfast. Being an amputee, she observes, makes it easy to cut through people’s pretenses and see what they’re really like—and in this happy instance, it revealed the trustworthiness at her boyfriend’s core.

“Given the choice, I’d pick dating as an amputee every time,” she concludes. But it took her a while to get to that point, as it does for most people. Amplitude has shared plenty of perspectives about amputee relationships and romance over the years, so with Valentine’s Day coming up we decided to revisit some of the wisest words we’ve shared on this subject.

“Intimacy is not just about sex.”

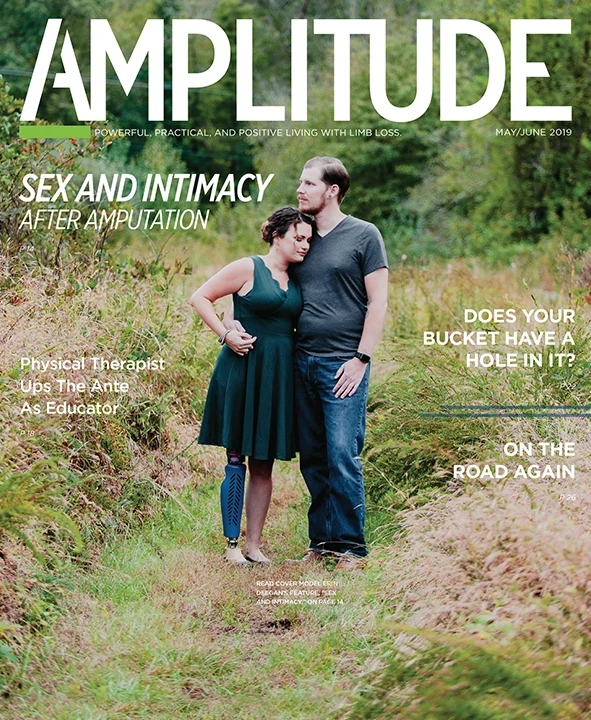

The most heavily clicked article in Amplitude‘s website history is “Sex and Intimacy After Amputation,” which originally appeared in our May/June 2019 edition. As the article noted, sex makes all the headlines and sells all the merchandise, but it’s actually intimacy that most people are after—and that doesn’t always have to be sexual. “Physical touch can result in the release of hormones that boost mood, so it’s not only part of relationship health—it can also influence the individual mental health of each person,” intimacy researcher Sara Hoover said in the article. Emotional intimacy is just as critical, she added, and it routinely occurs in nonsexual relationships.

As for the sex itself, Amber Blount said it’s going to be awkward at first no matter what, so just go with it. “It was like losing my virginity all over again,” she told Amplitude. “That super-uncomfortable, you-don’t-know-exactly-what’s-going-to-happen, what-is-the-other-person-thinking-about-you-when-you-take-your-clothes-off feeling. Plus, [guys] don’t know about my ‘cut here’ tattoo [on my residual limb].” “The main thing to focus on is communication,” Hoover concluded. “It’s not always easy and it definitely takes practice, but being open and honest about everything can help bridge the gap and lead to greater intimacy.”

“My worst scars were in my heart and mind, not my leg.”

Carolyn McKinzie and Paul Bernier shared candid “she said/he said” perspectives on their relationship in “The Dating Game,” published in our January 2021 issue. They had a ton in common, McKinzie recalled—the conversation was snappy, laughter came easily, and they both loved to hike, dance, and play the guitar. The biggest point of incompatibility was McKinzie’s lower-limb difference (Bernier’s able-bodied), and even that didn’t seen to be a big deal at first. But when McKinzie started having socket issues that limited her mobility a few months into the relationship, that’s when things got real. He got distant, she got scared, and when she confronted him things got pretty intense.

“I had been an amputee for 17 years,” she wrote. “I wasn’t some frail thing that couldn’t do anything for myself. I have been on my own for many years and don’t need someone to support me financially, physically, or emotionally. But I wanted him to know what I had been through and how damaging it had been. My worst scars were in my heart and mind, not so much my leg.” How did things turn out? Read on.

“I prayed my relationship wouldn’t change. . . . It all changed.”

“Yes, amputation changes relationships,” Alexandra Boutté wrote two years ago in a Valentine’s Day guest post. “But with communication and patience, it might bring you closer to the people you love.” That’s what happened for her, although it took time and effort to achieve that result. Cancer and limb loss radically altered her storybook romance, turning the early years of her marriage into something neither she nor her husband could have prepared for. “I couldn’t wash my hair, feed myself, or get to the bathroom without him,” Boutté recalled. “I stayed up nights wondering if this would break us—if it would break me. He hadn’t signed up for this.”

Neither of them had. But rather than breaking them, the challenge brought the two partners closer together than ever, adding a level of depth to their relationship they could never have reached via a fairy-tale existence. “We have been tested, and tested, and tested again,” wrote Boutté. “If just one of us had allowed this to consume us, we would not be where we are. Everything that happened made us feel even more connected.” Her advice for anyone who’s currently single, looking for a partner? “You’ve built up strength not many would understand. Love yourself first, just the way you are right now.”

“I felt like he couldn’t relate to me anymore because he was able-bodied.”

The outcome Alexandra Boutté feared after limb loss—the destruction of her relationship—very nearly came to pass for Yvonne Llanes. She and her husband, Darryl, struggled mightily after a drunk driver ran her over, costing her both of her legs. “I didn’t know how I was going to be a good wife, and I didn’t know how I was going to be a good mom,” said Yvonne in “Putting Love to the Test” (March/April 2020 issue). “For a long time, I couldn’t cope. I sat in my wheelchair and was so depressed. It just really sunk me deeper and deeper into that dark abyss, and I couldn’t get out of it.” Her husband worked long hours and was often too tired to connect emotionally; when he would attempt to, Yvonne would say angrily: “You’ll never understand, so why should I tell you? You have your legs—I don’t. It doesn’t matter what I say, you’re never going to understand.”

Although the Llanes eventually separated, they didn’t give up. Couples therapy eventually offered a safe forum for them to express anger, state needs, and forge a new level of honesty that saved their marriage. They also looked outside the relationship for fulfillment. Amputee support groups were particularly beneficial for Yvonne, allowing her to appreciate herself in ways that made her more appreciative of her husband and her marriage. “When we came back together, he and I both realized that we were going to have to communicate and tell each other our true feelings, even if it hurt the other person,” Yvonne said.

“In the beginning, you don’t know who you are.”

Limb loss even impacts relationships in which both partners are amputees—or so we learned in “Partners in Peer Support,” from our May/June 2021 issue. The couple, Tom Carlson and Kim Mylinski, met at the 2019 Amputee Coalition National Conference, where both had enrolled in the Certified Peer Visitor training course. They developed a friendship based on their shared desire to connect with and support other amputees, but it didn’t get romantic right away. Both needed to proceed cautiously, after having been burned in previous relationships. Limb loss contributed to the breakup of Mylinski’s marriage, leaving her so unsure of her identity that she didn’t feel ready for a new romance.

“It took a while to evolve back into myself and realize that I don’t have to be ashamed of myself or feel guilty about getting my needs met,” she told Amplitude. Carlson helped her get there—first as a friend, eventually as a husband. “We both understand the psychosocial and emotional issues that come with being an amputee,” she told us. “So we can provide that support to each other.”