by Chris Prange-Morgan

Finding inspiration in the world around us is a normal part of the human experience. We love heartwarming stories of people overcoming obstacles, pushing through adversity, and coping under extraordinary circumstances.

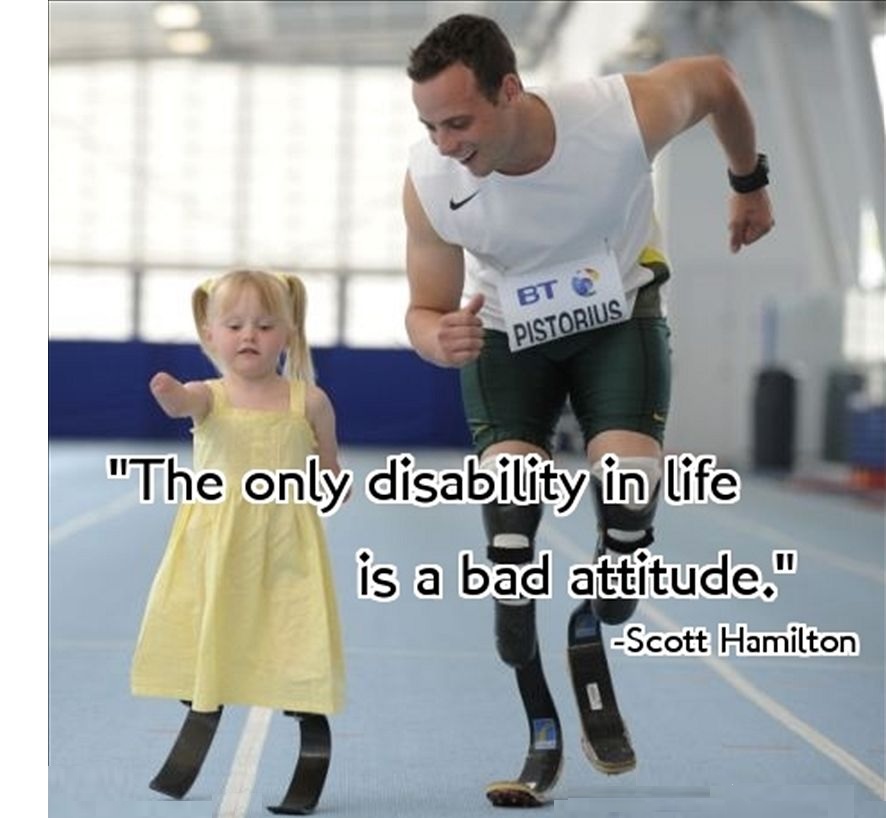

Some of the more common images in the media involve people with disabilities. We’ve all seen these stories and memes: A colorful image of an amputee running on a track citing the caption: “The only disability in life is a bad attitude.” A popular boy asks a girl with a cognitive disability to the school dance; they’re elected to homecoming court, and it makes the local news. A wheelchair user sits on a mountaintop with their hands in the air, and the quote below states: “What’s your excuse?”

There are two main problems with these sorts of images. One, they’re based on the idea that disabled people can do certain things “in spite” of their disabilities. And two, they’re primarily used to motivate and inspire non-disabled people. Australian comedian and disability rights advocate Stella Young termed these types of examples inspiration porn.

“When people say you’re an inspiration, they mean it as a compliment,” she said in her 2014 TED Talk. “We’ve been sold this lie that disability makes you exceptional, and it honestly doesn’t.” She continues, “I want to live in a world where we don’t have such low expectations of disabled people that we are congratulated for getting out of bed and remembering our own names in the morning.”

I’m a prosthetic leg wearer, and I’ve often pondered this subject because it brings up so many complexities and incongruities in today’s culture. Platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok have made images of people with disabilities more common than ever before, and that’s great. Corporate sponsorships and media opportunities have further raised the visibility of disabled athletes, models, and influencers—to the point where it’s now actually “cool” to sport your disabled badassery.

But I’m also cognizant of the fact that many brands capitalize on people with disabilities to promote their products. While not harmful per se, these campaigns fail to portray the challenges that most folks with disabilities face on a daily basis—beginning with lack of access.

“No amount of smiling at a flight of stairs will make it turn into a ramp,” Young states in her TED talk. “The issues in my life come not from the fact that I break my bones occasionally; they come from the fact that I can’t get into the vast majority of public buildings I want to get into.”

In a similar way, many people I encounter in the limb loss community tell me their struggles come from insurance denials and lack of affordability for the devices that would make their lives easier and more enjoyable.

I’ll admit, I’m a stubborn recovering idealist. Every time I see an image of a disabled individual in some kind of advertisement, I wonder how much that corporation has done to promote awareness and education. Has it lobbied for better laws and regulations to prevent insurance companies from exploiting loopholes to avoid coverage and leave disabled people behind? Beyond using the person’s image, has it embraced their community and lifestyle? Has it recognized their humanity as being just as full, rich, and meaningful as every able-bodied person’s?

Recently, I tried to secure a backcountry pass in Yosemite—not because I have a strong desire to backpack, but because I want to summit an amazing mountaintop. Since I’m walking on a prosthesis, this hike will take me and my family much longer than the average group, and we will require an overnight stay. I don’t want special treatment, but I need a backcountry camping permit to reach my goal.

After making several calls to Yosemite’s accessibility office, checking with the wilderness station, and navigating various online forums, I gave up. My situation didn’t fit into a typical stereotype, and I left the experience feeling mentally drained. Questions swirled around in my head pondering the limits of who is disabled versus who is not. Should the person who just had shoulder surgery be considered disabled? What about the person who swore they could lose 20 pounds by the time of their trip, but couldn’t? The person who had a knee replacement a year ago—what about them?

The definition of “special provisions” is a sticky one because there is no “one size fits all” approach to accommodating people with disabilities. The structures society has put in place in an attempt to navigate these questions often create more barriers—because we define the norm as zero impairment. But what if we were to ditch the dichotomy between “abled” and “disabled”? One of the benefits of the high media visibility achieved by people with disabilities is that the “Otherness” of our experiences is beginning to melt away. We’ve still got a long way to go, but people can now see for themselves the incredible abilities of people in the disability community.

I still feel a twinge of pride (mixed with embarrassment) when someone tells me that I inspire them. But I also feel compelled to share how fortunate I am to have the resources such as a great prosthetist and insurance to cover the devices I use. Others aren’t as fortunate—and that’s not okay.

I’m inspired every day by people of all kinds, including many who have no outward evidence of a physical disability. The human condition is fraught with an infinite array of challenges, which we can only appreciate by trying to understand one another’s circumstances. If images that inspire can ignite positive change, that’s great. But in the end, everyone seeks to be understood and to have access to the things that make us feel happy, connected, and fulfilled.

Those of us with disabilities are no exception.

Chris Prange-Morgan is an adoptive parent, patient advocate, trauma survivor, and hospital chaplain. She co-hosts the Full Catastrophe Parenting podcast with her husband, Scott. This article originally appeared in Psychology Today.