John Register discusses how to amputate fear and advance your career.

When John Register counsels amputees, he starts with a simple message: You have more worth in the workplace than you realize.

An LBKA since 1994, Register well remembers the difficult process of tearing down his old thought patterns and rebuilding his sense of self-worth after losing his leg. His amputation destroyed his lifelong dream of competing in the Olympics, leaving him without a goal to focus on and no clear definition of what it meant to be successful.

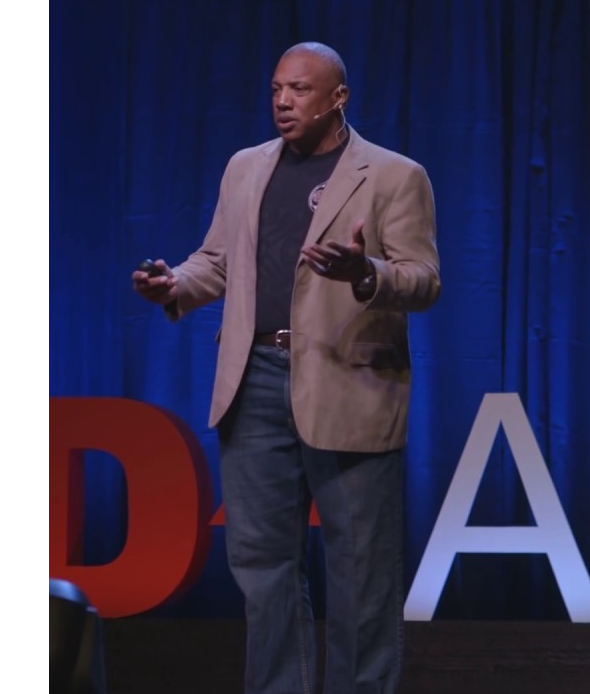

But in the years since, Register has used his own story of limb loss to succeed in ways he could not have envisioned. He’s become a sought-after business consultant specializing in communication and workplace diversity, advising corporate giants such as BioGen and federal agencies such as the U.S. State Department. He’s written a book about leadership, hosts a long-running podcast, and is a repeat TedX speaker. Since 2018 he’s served on the the Amputee Coalition’s board of directors. And along the way, Register achieved his goal to compete against the world’s best athletes, winning a silver medal in the long jump in the 2000 Paralympics.

“You have to build your own empire,” Register says. “And you do that by being authentic to who you are and being true to whatever it is you’re trying to accomplish.”

That philosophy resonates far beyond the limb-loss community. It applies to any professional or organization that’s facing adversity—and who isn’t in 2020? But as Register routinely tells clients, crises often spur creativity and obstacles usually present opportunities. On the eve of National Disability Employment Awareness Month, we caught up with Register to get his views on the career landscape for amputees in 2020.

Paralympic medalist in the making

How has the pandemic affected your business? I can imagine how it might be either a blessing or a curse.

COVID, it’s been interesting. Everything shut down, everyone started wearing masks, no one’s traveling, and the whole industry stopped. That was a challenge for sure. So after I mourned the loss of all my dates flying off the calendar, I chose to focus in on the mission. And the mission is to work with business professionals to help them hurdle adversity and amputate fear. I do it through storytelling, using my story of how I overcame adversity—which is not defined as the amputation of my left leg.

How do you define it?

I frame that in three ways. The first thing I had to overcome was my own personal fear of how people were going to perceive me. The second was other people’s beliefs about what I can or can’t do, which is based upon what they believe they could or could not do if they were in my situation. They’re trying to hold me back to a former self that makes them feel comfortable.

I then went on to this third step, and that’s the courageous step. If you know something to be true, can you stand on that despite other people’s opinions, despite anybody else not being able to go with you? I chose to amputate the fear of how other people saw me, or how society saw me, and amputate that fear that I’m not going to be good enough or worthy enough.

A lot of people, after losing a limb, think their life is over. And I get where they are. I was there. I remember the day. It was June 17, 1994. I’m watching the OJ [Simpson] car chase at 5 o’clock in the afternoon, and I’m in the most pain I’ve ever been in in my life. That was one month to the hour after my injury. I’m a fresh amputee. I’ve got phantom pains that are killing me. I’m in tears. I can’t get any rest. I can’t sit any way and get comfortable. And I’m at my cousin’s house watching the OJ chase. And he wrote a suicide note.

Right, I remember. They read that note on the air, I think.

They did. They did. And that perked me up. I’m biting my lip and through my tears, I said to myself that no matter how bad it gets, I’m not checking out.

So that kind of snapped you out of it.

Well, that was the second snap. The first snap was when my wife told me, “You know what? We’re going to get through this together.” Later on, I began to define what that meant, and what it meant to have a new normal. But the first step was to identify what fear I needed to amputate to know I had worth, no matter what others believe. In my case, that was doubt about measuring up to other people’s expectations. It’s like I felt embarrassed about being an amputee. I worried about how people were looking at me. You have to choose to amputate an old mind-set and know that you can never go back to it. I tell people, “You don’t get this in a book. You have to do this work. No one else. You do it.”

That’s a scary place. That’s a hard thing to get over. But once you understand that and amputate that thought process, then you can live more fully. You can move forward.

Help me translate this into a professional context. If I’m an amputee in the workplace, what practical steps can I take to put this philosophy into practice?

One way is to either start or join an employee resource group or business resource group. The second way is to be matter-of-fact about your amputation. You’re not shying away from being an amputee all, but you’re not defined by it either. Then, when there are issues going on in the company—like now, with what we’re going through now with COVID, or with the difficult conversations people are trying to have about race relations—in those moments, you can go to leadership and let them know: I went through a tough time. I had to bounce back from this amputation, and it took a lot of wherewithal. I had to relearn some things. I would be happy to share this with the team. You offer to share your story as a point of comfort for others.

The fastest to get over the mindset of amputation are military service members. [Note: Register served six years in the U.S. Army and was deployed during Desert Storm.] The reason for that is because when they came into Walter Reed, the Naval Hospital, or whatever, they healed together. They all were in the same battle, the same firefight. They all had the same mission. Every one of them wanted to get back into the field. They felt like they let their battle buddies down because they got hurt.

I tell that to people who are in transition in their work environment, like I was. You’re not going to dictate my life for me. Take ownership of your career, assess the tools you have, and start reconstructing, rebuilding. Because most people, when they go through some type of trauma, there’s nothing left anymore to rebuild on. You have to build a new foundation. You’re constructing a new foundation. You’re digging again.

Do you think most amputees recognize that their experiences of adversity and resilience are a professional value-add in today’s environment?

I don’t think most people necessarily have that recognition. I even run into this myself. I’ll deflect. I won’t always talk about my own story. It sounds like I’m bragging, and I’ve never been able to do that. I don’t like to toot my own horn. Sometimes people have a comfort with the old stigma. That’s when you know they haven’t truly let go, they haven’t amputated that fear. If you’re thinking, “I’ll just accept the way other people see me,” that’s a mindset. And it’s an old mindset: “If I don’t have my leg or my arm, therefore I’m less than.”

Power is static, and status is fluid. If you are preoccupied with status, that puts you in a fluid position where you’re relying on the status other people give you. I tell amputees: You have the power. You’re in the driver’s seat. You’re resolved. You know exactly who you are, and you’re standing on such a powerful truth that no one can push you off it. You’re standing on that power, and that equals your liberation.