Snorkeys, Hoppers, Flat Tires, Broken Wings, and the legendary Con Yannigan.

Photo from National Archives.

Little did we realize when we wrote about amputee pitcher Monty Stratton just how rich a vein we’d drilled into. It turns out that dozens, or more likely hundreds, of limb-different ballplayers have been lost to history.

Well, almost lost. . . . we rediscovered them, after all. But it took a little bit of luck and a lot of vigorous burrowing on the Internet to mine this information. And there’s definitely more to be salvaged—we’ve reconstructed part of the timeline, but there are still some lengthy gaps during which amputees were definitely playing ball without leaving much documentation behind. The longest-running amputee baseball series covered at least 20 years (roughly 1930 to 1950), but we only found the scores for five of those games. So far.

We’ll fill in the blanks some other time. For now, on the eve of MLB’s long-awaited Opening Day, we present our findings to date.

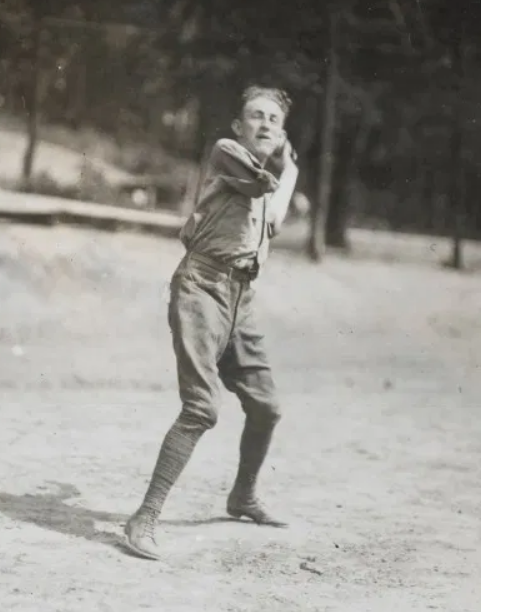

c.1880s: Con Yannigan

Everything we know about Con Yannigan comes from a single passage in an old newspaper clipping discovered by John Thorn, the official historian of Major League Baseball. Yannigan, according to the 1898 article, “made a big reputation around Hartford, Connecticut, several years ago. He was a first baseman and had a cork leg. . . . A great play of his was to block off base runners with his game leg. Opposing players could sharpen their spikes to a razor edge, but ‘Con’ didn’t scare for a cent.”

Thorn came across this item while researching the origin of the baseball term “yanigan” (slang for a second-string player), and he’s not at all convinced that Con Yannigan really existed. Neither are we: We can’t find any reference to anybody named Con Yannigan (or “Yanigan”) at Baseball Reference, the New York Times archive, the Library of Congress, or the U.S. Census for 1880, 1890, or 1900. Thorn’s only piece of (semi-)corroborating evidence is an 1893 newspaper article in which a 19th-century catcher named Con Daily is referred to as “Connie Yannigan Daily.” This article, Thorn notes, “may have recalled a real player who went by the name of Con Yannigan, or made sly reference to an emergingly legendary one.”

We like this story too much to write Con Yannigan off as a complete fabrication, so we included him here. If you’ve got an old baseball card of this guy in your attic to prove he really existed, please contact us.

1880s: Snorkeys vs. Hoppers

We’ve got solid documentation for these two teams, who played at least once (and perhaps a few times) in Philadelphia in May 1883. The contest(s) matched a lineup of upper-limb amputees (the Snorkeys) against a roster of lower-limb amputees (Hoppers). All but one of the participants lost their limbs on the job while working for the Reading Railroad.

Reporting on a May 23 contest, the National Republican of Washington, D.C. noted: “Four of the Snorkey team had an arm off at the shoulder, one had a paralyzed arm, and each of the rest of the team was minus a hand.” As for the Hoppers, “their first baseman had an artificial leg, the center and right fielders chased balls on crutches, and the others of the nine traveled on ‘peg’ legs.” The Republican put the final score at 34-11 Snorkeys, although other sources place the tally at 33-17.

“An immense crowd witnessed the game,” the Philadelphia Times added, “and there were some remarkable feats with the bat and ball. . . . Their success was so great that it has been resolved to take them on a tour to New York, Chicago, St. Louis, and other cities.” We have no evidence that such a barnstorming tour ever took place, but we do know the teams faced each other again in 1887. The Portland (Maine) Daily Press had the Snorkeys and Hoppers scheduled to play in Philadelphia on September 12, 1887, and the illustration shown here is presumably from that game—it appeared in the October 29, 1887, edition of the National Police Gazette.

Given the apparent success of the original contest, one suspects there were additional games between 1883 and 1887. But until we have proof, the 1884-1886 Snorkeys-Hoppers series can only be assumed.

Photo from National Archives.

1917-20: WWI and the Red Cross

An estimated 4,400 American soldiers lost limbs in combat during World War I. Most of them convalesced at military hospitals operated by the American Red Cross’s Department of Military Relief, and several of these institutions formed amputee ballclubs to boost morale and promote physical recovery. Fort Des Moines had separate rosters of upper- and lower-limb amputees, while Fort McHenry and Walter K. Reed pitted teams of upper-limb amputees against able-bodied players (who competed with one arm immobilized).

Elbert K. Fretwell, the department’s director of recreation, encouraged baseball as part of a broader program to provide “reconstructive recreation for our sick and wounded soldiers, sailors, and marines—our own men who for their Country stood ready to give if necessary their last full measure of devotion.” As so often happens, adaptive sports gave rise to other initiatives for reintegrating amputees into the world. The Red Cross opened the nation’s first institution specifically devoted to amputee rehabilitation, and Congress passed legislation to support job retraining for disabled veterans.

Another significant outcome of World War I was the creation in 1919 of the National Amputation Foundation (NAF). That organization gives us a direct line of descent between the wounded vets who played ball at Red Cross hospitals after the war and the Golden Age of amputee baseball, which dawned about a decade later.

1930s-1950s: Flat Tires vs. Broken Wings

The New York Times of July 15, 1935, reported on an annual baseball game between the Broken Wings—described as “veterans who lost an arm in the war”—and the Flat Tires, who lost one or both legs in the fighting. At stake was the title of U.S. World War Amputations American Legion Championship, awarded annually by Post 116 of Brooklyn, New York.

“A fast-moving game held 1,000 spectators in rapt enthusiasm at Marine Park,” the Times gushed. “The war heroes fought for the title as doggedly as they had fought on the front lines in their youth. . . . Flat Tire hitters, some with artificial limbs and some on crutches, ran the bases with ease, sliding into the cushions with agility.” The Flat Tires won the game, 14-9, the first time (according to the Times) they’d defeated the Broken Wings in five years—from which we can conclude that the series began no later than 1930.

We can’t find any other coverage of the amputee baseball championship from the 1930s, but the Wings and Tires apparently kept playing for the rest of the decade and into the 1940s. By 1947, when the subject resurfaced in the Times, the Broken Wings had recorded eight wins in the annual tilt, versus six wins for the Flat Tires. That makes a total of 14 games between 1930 and 1946, or one a year, with the contest presumably suspended for a few years during World War II.

Speaking of which: World War II created a new generation of amputee soldiers and propelled amputee baseball to unprecedented levels of visibility. Between 1947 and 1950, the Broken Wings and Flat Tires played their annual game at the Polo Grounds, the most hallowed ballpark in major league baseball and home to the New York Giants. The event drew tens of thousands of paying customers, with the money earmarked for the National Amputation Foundation’s new amputee rehabilitation center on West 24th Street in Manhattan. Hollywood and Broadway celebrities performed before the game to drive up attendance, and in 1950 they actually donned uniforms and took part in the action. The previous year Li’l Abner cartoonist Al Capp donated the artwork for the official game program.

Beginning in 1948, the game became a vehicle to raise awareness about disability and to promote employment for amputee soldiers. NAF director Sylvan Gans told the Times that “the most important point amputees were trying to get across to the public was the fact that despite their handicaps they were able to work and would hold on to their jobs even better than persons without physical handicaps.” Prior to the 1949 game, Mayor William O’Dwyer issued an official proclamation declaring “Employ Amputees Day,” noting: “[I]n common with civilian amputees, these veterans often have difficulty in finding employment although they are capable of doing useful work. . . . [M]odern prosthetic devices have given them a dexterity and ease of movement hitherto unknown, and . . . I urge business men of our city to give amputees equal opportunities for employment.”

The series came to a screeching halt in 1951, when the annual Broken Wings v. Flat Tires game was replaced with an exhibition fundraiser between the Boston Red Sox and New York Giants. The money went for the same cause, i.e. the NAF’s amputee center, but the game no longer featured amputee players. Our hunch is that, as veterans got married and fanned out into the suburbs, it became increasingly difficult to muster a full team of amputee players and keep them sharp enough to play a creditable nine innings. Perhaps the fans themselves lost interest as the war receded into the past and was superseded by the Korean War.

For whatever reason, amputee baseball has yet to regain the level of visibility it enjoyed in the immediate postwar era.