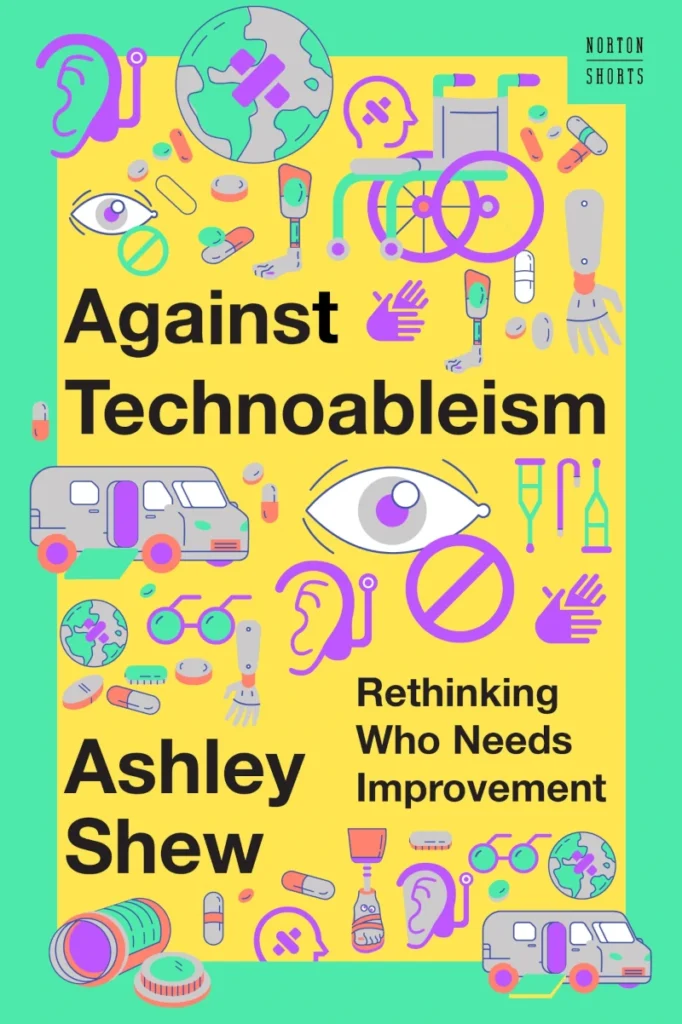

“A lot of people in the tech field see disabled people as test pilots for new technologies,” says author Ashley Shew. And that’s good, because it leads to lots of disability-focused innovation . . . . right? Shew, who had a rotationplasty amputation in 2014, isn’t so sure about that. In her new book, Against Technoableism: Rethinking Who Needs Improvement, she draws a sharp distinction between technology that’s intended to herd disabled bodies toward nondisabled standards, versus that which actually liberates people with disabilities to live their lives as they choose.

Against Technoableism grew out of Shew’s work at Virginia Tech University, where she’s an associate professor of Science, Technology, and Society. The book has been generating conversation well beyond the disability niche. NPR’s Science Friday did a segment on it, the New York Times gave the book a glowing review, and some of its chapters are already finding their way onto university reading lists. The attention is a measure of how well Shew blurs the (artificial) distinction between disability and nondisabledness. “I want to see disability portrayed as normal and not make it a weird thing,” she tells Amplitude. “Disability is normal and natural. It’s a normal part of human life. . . . If you want to plan a good world, you need to listen to disabled people.”

You can get a copy of Against Technoableism all over the place, including our go-to online outlet, Bookshop.org. Visit Shew’s webpage for links to more reviews and interviews, as well as a discussion guide to the book. We spoke with Shew last month; our conversation is edited for clarity and length.

Why do you think this book is garnering so much attention? Is it just a good job of marketing, or are we in a moment where there’s a particular receptiveness to and interest in the issues you’re raising?

That’s a really interesting question. My book markets to a number of different audiences. It has aspects of science and technology journalism to it, and I think there is a real thirst for science and technology journalism, especially as our world is very much technologized. With AI being the latest example.

The stories we get are often singing the praises of technology. But most people in their daily life realize that technology is a lot more frustrating than any of those news stories reflect. It’s often disorienting in ways people don’t account for. People aren’t so excited for the next update to their operating system, or when their workplace moves from Google Suites to Microsoft Office. It causes all sorts of problems.

That’s a conversation that people already are having, and it includes a lot of relatable experiences that fit really well in the disability world. We always think technology is going to be good for disabled people. But you get a new prosthetic leg and it walks a little different, so then you have to walk a little different, or you have to switch feet. Or maybe you have to switch tools on the end of your prosthetic arm. It’s not always smooth. That’s a disability experience that’s relatable to anyone. So the book comes at the nexus of two things that I think are of interest to a lot of different groups of people.

There’s a lot of commentary in the book about how some technological solutions seem designed to erase disability, rather than accommodate it. That echoes the ambivalence I often sense among amputees about identifying as disabled. There’s a lot of praise around the idea of overcoming disability, holding it at arm’s length. What paths do you see toward a world in which disability carries positive associations—where it’s actually kind of cool to belong to this community?

This is a conversation I have with people from other disability groups as well. We all have our own brand, right? We all have our own thing. So how do we interface with a larger disability community?

Disability is kind of a made-up category. The fact that amputees and dyslexic people, people with bipolar depression, little people, deaf people—the fact that we are all in the same category is based on how we’re seen societally. It doesn’t say anything about you personally, except to say how you are viewed. And even if you don’t think of yourself as disabled, you’re considered disabled and treated as disabled by other people. In fact, the Americans With Disabilities Act covers you whether or not you consider yourself disabled.

When we study the history of the ADA, or the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, it included advocacy from many different types of disability groups. It required this larger effort that recognizes that all of us are experiencing discrimination. It required solidarity with one another, because once we start allowing discrimination for one subtype of us, then none of us will have any protections. So the solidarity required to get this off the ground is part of what holds the community together.

Even with those laws, our legal structure makes it really hard for disabled people to get what we need. There are no ADA inspectors to check things out and ensure compliance. We have to sue in order to enforce the law, and that’s a flaw in the system. This could still be better. I don’t know that everyone needs to go around saying “I have a disability” and calling attention to that. But we do have to fight for one another. We need to be knowledgeable about our community and connected with each other in order to move forward.

If I define “technoableism” as, roughly, technology that confines disabled people as much as it liberates them, or maybe even more than it liberates them, who’s out there who is working toward a vision that’s not technoableist?

There are people in the amputee world that I think are promoting visions that are more true to life. One of those is Jordan Reeves, who wrote a book with her mom called Born Just Right. She’s got this perspective where you can make cool things, have fun, and get interested in STEM education, but it’s not like the technology saving you. You’re doing the saving, because you’re creating cool things for yourself. I also really like Josh Sundquist, and I appreciate that he appears in public so often without a prosthetic limb. So many times, amputees are told that your prosthesis is your redemption. I like that he doesn’t buy into that. He doesn’t appear the way people expect all the time, and he owns it.

Outside the amputee world, I really appreciate the work Alice Wong is doing. She has the Disability Visibility Project and has been writing for Teen Vogue. She writes a lot about her experiences with Medicaid, with different technologies, with becoming a nonspeaking person, and the progression of her disability. She’s also lifting up other disabled voices along the way with the Disability Visibility Project. I really think the work she’s doing is critical. I also like Amani Barbarin who goes by Crutches and Spice on TikTok. Amani has cerebral palsy, and she has lots of political messages to deliver but also like fun, passionate advice. She’s all over the place, and doing a lot of like disability related journalism as well. And it’s really cool.

I’m curious if you have any thoughts about how the conflict in Ukraine has been covered. There has been a lot of coverage (including in Amplitude) about the technology that’s being sent there to support wartime amputees. Where do those narratives fit into the technoableism conversation?

When it comes to the casualties of war, the conversation tends to get cast in the language of compensation, especially in the United States. People deserve to have intact bodies because they’ve made sacrifices—they’ve paid with their bodies—so there’s this necessity to invest in technology, invest in rehab hospitals, in the wake of war.

But we should want technological innovation with or without war. I want society to care about disabled people at times that are not war-based, and to care about people who aren’t disabled because of a traumatic injury. We know that most of the amputations in the United States are from diabetes complications and peripheral artery disease. I want society to invest in this problem and listen to this population, too. In the book, I talk about the reporting by Lizzie Presser about the Black amputation epidemic. If you look a map of where the most amputations in the United States are coming from, those are geographically concentrated in poor, rural areas. A lot of these issues are about preventative and primary care, which can be mapped in a particular way and related with the deep income inequality that exists. I wish we cared about those stories enough to invest in this area, because look at all these amputees that we’re causing through medical neglect.

That’s story’s a lot less sexy than a story about a really cool new prosthesis that can restore function, as opposed to looking at common-sense preventive measures that can prevent limbs from being lost in the first place. It doesn’t draw the same level of clicks.

No, and it deserves a lot more coverage. And more coverage would actually lead to better funding for what is essentially basic healthcare. It’s not anything we don’t know how to do. It’s not pushing the line, but it is doing something really important.

And it really is speaking directly to the subject of your book. I mean, preventive healthcare is technology. It’s just not the kind of technology that is considered thrilling or exciting.

But it’s technology that already exists.

If we imagine an evolution toward a use of technology that’s more appropriate and that really serves the needs of people with disabilities, how do you view this moving forward?

One thing technoableist narratives do is make us think that technology will completely eliminate disability in the future, or that it will make disability less of a problem or a problem for fewer people. I think this is a denial of reality. There has to be an acknowledgement that we’re going to have more disabled people in the future. In so many different categories, we’re already seeing higher rates of disability. We have tick-borne illnesses in many more places, we have malaria in more places because of climate change. And even if you don’t think climate change is real, the disease patterns are changing, regardless of what you think is causing it. Our air quality is getting worse, which means we have growing rates of asthma in cities, more people with COPD, different types of cancer, breathing difficulties, brain damage, all sorts of things.

There are all these ways in which the trajectory we’re on is one of having more disabled people, not less. So there’s an imperative to plan for that. Part of that means changing our media narratives immediately. I want to see disabled people as part of the future. I want to see disability portrayed as normal and not make it a weird thing. Disability is normal and natural. It’s a normal part of human life. It’s just part of our existence.

And it’s something that actually adds a lot of value. We adapt, we figure out how to do things in new ways. That can be a source for creativity. Not every part of it is fun. We still don’t like pain. But disability offers ways of thinking about how we adapt and exist in our everyday lives that can be really generative for planning for human futures. If you want to plan a good world, you need to listen to disabled people.