“I lost my leg in a crush accident,” says Albert Lin, “so to see it happen again was a bit jarring. I don’t know anybody else who’s lost the same leg twice.”

Lin is describing one of the many mishaps he endured during the making of Lost Cities Revealed, which debuted last week on National Geographic. The long-awaited followup to Lost Cities with Albert Lin (whose two seasons were released in 2019 and 2021), the new series was filmed over three arduous years on four continents. Lin and his production team endured no fewer than three near-fatal accidents, two arrests, the loss of their cameras in an Amazonian rapid, and an assortment of scorpion bites, broken bones, civic uprisings, and other catastrophes—including an eerie echo of the misfortune that made Lin an amputee in the first place.

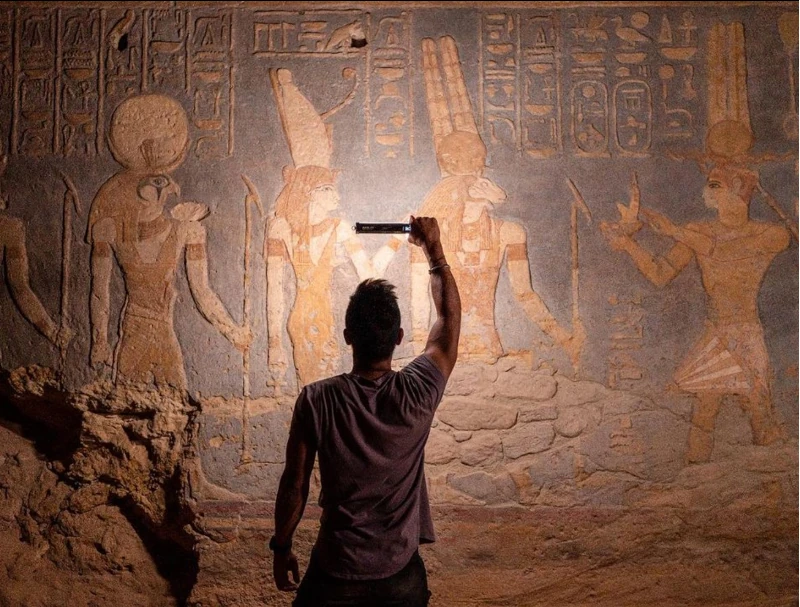

But then, Lost Cities is all about echos—about ancestral voices and narratives that are still embedded in the landscape, and which we can still hear if we open our ears to them. “Each episode is an opportunity to tap into these profound, deep insights of our humanity,” Lin told Amplitude earlier this month. “We’re not looking at each civilization from the standpoint of just the buildings. We’re looking for nuggets of wisdom—some kind of connected wisdom across humanity.”

If you’re not familiar with Lin’s backstory, you can quickly get up to speed here. Lost Cities Revealed airs Thursdays on National Geographic Channel, and all the episodes are available on Disney+ as of today. The conversation below is edited for clarity and length.

Judging from your social media feed, it sounds like you had a lot of hazards thrown at you during this production. Can you share some of what happened, without giving away any spoilers?

Oh, man. What a journey. For some reason, everything just felt bigger and more heightened, both in terms of our discovery and our ambitions. We were in Sudan a couple of months before the coup [in 2021], so everything in Khartoum is intense. There are peaceful protests that quickly escalate into riots, and then all of a sudden you hear the flash bombs, and the tear gas comes wafting in. Our cars are kicking up dust, which puts the tear gas in your eyes, because there’s so much of it. Your eyes are burning out.

Having a big camera crew out there makes you a target. We got fully arrested—all of our passports confiscated, all of us carted off to this big intelligence room—and it was very intense. We’re sitting there, and they’re looking through our papers, and everything is just very heavy-handed. And then about halfway through, the second in command of this unit comes over asks for a photo. It turns out that they’re big fans of Lost Cities—National Geographic is one of the only English- language channels in a lot of these remote places—and that got us out of hot water. It started out rough in the streets, and then it ended with us all standing there for a big group photo. So that worked out pretty well.

There were some other, more intense moments. We were on the headwaters of the Amazon, in a place that is extremely remote. Had we made two more turns down this river, we would have been in a section that you can’t get out of for a week, because there are no roads, there’s nothing—you’re down in this narrow canyon. Right before we got to that point, our camera crew raft flips in this huge water. We lose all the cameras, and most of the crew starts popping back up with their life vests, but two of them get held way down for a really long time. And when they pop up, you can see in their eyes—I was right there waiting, I was closest to one of them. I reach down and grab this guy out of the water and pull him into the raft, and I just hold him as he cries, having faced his moment of death. I mean, that was a moment. We stood the shoot down. We needed to regroup, and we came back months later.

And then, probably most apt to what you and I know about, I was in Israel on a story about the Canaanites. We’re up high on this cliff, looking for a lookout tower that we had seen evidence of. It had just rained, and these huge limestone boulders that I was climbing up were looser than I thought. And as I’m up on this boulder, all of a sudden it starts opening up, like a door. I start falling back, and I’m about to die—it’s about to crush me. I’m leap-frogging to try get out of the way in time, and I hit the ground, and then my mind slows down and I’m thinking: When’s it gonna hit me? What part of me is it gonna hit? Am I gonna die?

It comes down, and it doesn’t hit me. I’m on the ground, and I’m looking around and asking, What’s bleeding? Do I have any scars? I’ve got some cuts and scrapes and things, but everything’s okay. So I go to stand up, and all of a sudden I fall to the ground again. I look back down, and there’s my body, then there’s the boulder, and then I see my foot on the other side of the boulder.

And the rest of the prosthesis is under the boulder?

It was all smashed—all the carbon fiber, everything. It was all destroyed. It was gone. I don’t know of any other stories—maybe you do—but I don’t know anybody else who’s lost the same leg twice.

When you realized what had happened, did it trigger some traumatic flashbacks or anything?

Yeah, for sure. I lost my leg in a crush accident, so to see it happen again was a bit jarring. We were on this remote cliffside, and what I am I going to do out there? A sound recordist gave me his boom stick, and I used that as a walking stick to hobble my way back to where our trucks were. It was pretty intense. Everybody was in a state of shock. We took the next day off and didn’t work; we stood the whole thing down. It definitely reverberated for a while.

But it made me think about why I do this stuff. These expeditions have a bigger purpose than myself. We’re making discoveries about our human genesis; we’re making discoveries about our story to figure out who the hell we are. And in doing that, we get this deep wisdom, this deep knowledge that we all carry with us, no matter where you’re from. And that, to me, is incredibly important.

The second thing is that our realities are limited only by our imagination. You know from my story that when I saw that picture of Mike Coots on his surfboard while I was lying in a hospital bed, that image did everything for me. That changed everything. It changed my whole perspective. When you see images that allow you to reimagine things, your reality is expanded. So if these shows can have meaning for somebody in a similar way that Mike’s image had such deep meaning for me, then I’m paying forward with gratitude what he gave me.

Tell me a little more about the deep wisdom you were trying to tap into as you explored these ancient places. What are some of the lessons, the wisdom, that you discovered while producing this season?

In the episode I was just talking about, the story about the Canaanites, the geological record shows that during their time there was a huge megadrought. It has its own geological name, the 4.2ka event. It actually might have spurred the collapse of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus River Valley. The first big civilizations might have collapsed because of this climate event. We found a story of some people who turned toward the coast as this was happening, and they created this international trade network with all the people they could connect with. You see artifacts from all the different areas coming to this one hub, huge vats of wine and things like this from all over the ancient world. An archaeologist had been excavating the site, and when we did all these scans we discovered that it was actually part of a much bigger city. And the city had all these components that were quite egalitarian. It had a huge series of communal halls, but there wasn’t any big throne or central royal palace. So it felt like what I was seeing is that, in the face of this great shifting moment in our human story, the people who made it were the ones who figured out how to work together and communicate with their neighbors.

Another episode is in Chiapas, Mexico, where the Lacandon still live—the last of the Maya. They’re still around, and the words that they use are ancient words. When you hear them out loud, you hear the echoes of the ancient past. A lot of linguists say that when you speak in a different language, you actually think differently, because the framework you’re applying, your description of the world, is captured in those words. For the Maya, for the Lacandon, everything has a soul. The trees, the rocks, the machetes, they all have a soul. We’re all part of some large collection of souls. And it really made me think about the wisdom we had before we separated ourselves from nature. At one point, we were deeply understanding that we are part of nature, and then we kind of pulled ourselves away from it.

For me, it’s humbling to realize that the Mayan culture was once as grand and powerful and sprawling as our own culture is, but it eventually collapsed. As the Canaanites’ did.

One of the most special episodes was in Palenque, which is a very iconic site of the ancient Maya. It’s when they were in their prime. The site of Palenque is huge. It’s full of these massive pyramids, and a huge portion of it was built by one ruler. His name was Pakal. We got access to the heart of his tomb, right in the heart of the pyramid, and you see all these glyphs on the walls that describe the Maya origin world. It’s powerful, but you also know that it was only a couple generations after Pakal that Palenque fell. They Maya are such a charismatic civilization, because they rose out of the jungle, and then they have these moments of collapse, rising, collapse, rising, collapse, rising—and they’re still here. And the Lacandon give us these windows into what you just described.

The Lacandon believe that each tree has roots that are connected to the stars, and every time you cut a tree down, a star falls. When you cut all the trees down, all the stars fall, and you’re done. So when you look at the expansion of Palenque, it took a huge number of trees to create that city. They deforested the hell out of that jungle. So maybe the story the Lacandon are telling is about what happens when you cut away all of nature, when you overpopulate and build these huge urban centers but you don’t have the resources to sustain the place, then it leads to big conflicts, big wars, big fights. The people in Palenque had a term for these conflicts. They described them as “star wars”—wars at a cosmic scale, wars that literally made cities and entire empires collapse. So what I see in the Maya is this vignette about how they rose, took over nature, and forgot they are part of lots of souls, not just human souls. And that led to this overuse of resources, which led to fighting, which collapsed everything that emerged out of that very source of nature itself.

These sound like very relevant issues—a little too relevant, honestly. I’m starting to see what you mean about how this show taps into timeless wisdom that unites the present with the ancient past.

And it’s just being revealed. A lot of this stuff feels so ancient, even though it wasn’t that long ago. With these new technologies like LiDAR, and all the VFX we’re putting into the show, we’re rebuilding these worlds and bringing them back to life. So hopefully viewers walk away feeling like they’ve seen something that is actually real. Our access to these stories now is more authentic and more incredible than ever. These things were real. They are real. And I’m starting to get a sense that there’s some kind of deeper shared knowledge that humanity has always had, these profound deep insights, that we somehow forgot and need to rediscover. That’s just beginning to come into my consciousness. I can almost touch it. The series has all these huge moments of discovery, and that made it very personal and profoundly more meaningful to me.