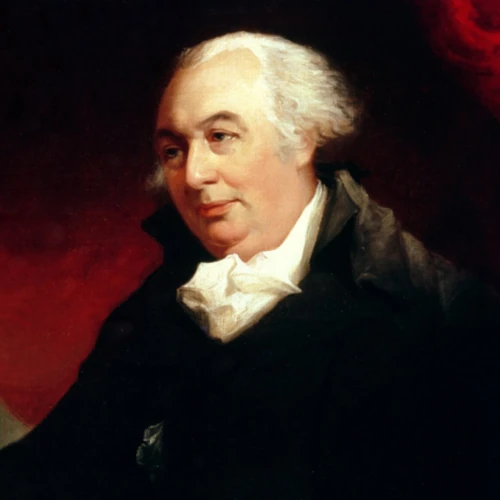

Gouverneur Morris, the below-knee amputee who wrote most of the US Constitution, is finally receiving long-overdue attention from historians. The last few years have brought a wave of new scholarship documenting how profoundly this individual influenced the nature of our republic. Researchers have unearthed Morris’s eulogy at Alexander Hamilton’s funeral, the particulars of his post-amputation treatment, the unsolicited military advice he offered George Washington, and other tantalizing, titillating details about his life.

Here are a few of the juiciest items that have gained attention in recent years.

His recovery from limb loss may have been aided by the affections of a prominent married woman.

Morris was kind of the Warren Beatty of his day, an enthusiastic philanderer whose amorous exploits generated endless amounts of gossip and rumor. Those stories didn’t end with his limb loss. On the contrary, whispers quickly emerged that he’d shattered his leg leaping from a third-story window in a panicked escape from an adulterous tryst. It’s a good story, but probably untrue—all the evidence suggests his injury was caused by a less scandalous mishap (a carriage accident). However, there are credible indications that during his recovery, Morris seduced Elizabeth Plater, the mistress of the household in which he convalesced. Mrs. Plater’s husband, George, had served alongside Morris at the Continental Congress of 1778. John Jay, who presided over the Continental Congress and knew both men, wrote to a colleague that although Morris’s limb loss “has been a Tax on my Heart, I am almost tempted to wish he had lost something else.”

He apparently salved his post-operative wound with homemade, rum-based vinegar.

The accident occurred in Philadelphia in May 1780. The most detailed description of the incident comes from William Churchill Houston, yet another Continental Congress delegate. “He was riding out in a phaeton,” Houston wrote, “and the horses taking a fright ran away in the street, struck the carriage against a post, broke it all to pieces and in the shock fractured Mr. Morris’s ankle to such a degree that it became necessary to take off his leg immediately. He bore the operation with amazing firmness.” The amputation was performed by a surgeon named James Hutchinson.

According to recently discovered receipts from a local shopkeeper, Morris’s post-op medical supplies included a gallon of vinegar, a pound of raisins, five pounds of soap, and—tellingly—a quart of molasses and half a gallon of rum. The latter two ingredients figured into a popular formula for making vinegar, a common disinfectant in those days. American soldiers used the rum-molasses concoction to treat their combat wounds, and it seems to have worked in Morris’s case. He did not suffer infection, regained his health without complication, and never required any further surgery on his residual limb.

He gave unsolicited military advice to George Washington—and lived to tell the tale.

Morris’s amputation occurred in 1780, during a difficult stretch of the Revolutionary War. That fall, with the colonial army struggling to make headway against the Redcoats, Morris (still recovering from his injury) cooked up an invasion plan to run the British out of New York City. Morris wrote to Washington with a detailed outline of the attack, which he modestly described as “a brilliant stroke” that would lead to subsequent gains in the South. The general didn’t take kindly to the suggestion, and in his response Washington showed a flash of his well-known temper. The proposed scheme, he wrote to Morris, displayed “how little the World is acquainted with the circumstances and strength of our Army.” The men were underfed, poorly provisioned, and discouraged. Communication among units was sporadic, making it difficult to coordinate troop movements, and Washington’s own command was so broke that he was covering expenses via his personal funds. In a caustic conclusion, the general allowed that Morris’s plan might work if the colonial forces “could live upon Air—or like the Bear suck their paws for sustenance.”

During debate over the Constitution, he denounced slavery more forcefully than anyone else.

Given the tenuous state of the Union in 1787 and the vehement differences of opinion over the question of slavery, most delegates to the Constitutional Convention went out of their way to avoid direct confrontation over the issue. Not so Morris, who assailed the proposed “three-fifths compromise” (which was ultimately enshrined in the Constitution) with absolute fury and zero restraint. “Upon what principle is it that the slaves shall be computed in the representation?” he asked. “Are they men? Then make them citizens and let them vote. Are they property? Why then is no other property included?” The three-fifths compromise, Morris argued, meant that “the inhabitant of Georgia and South Carolina who goes to the coast of Africa, and in defiance of the most sacred laws of humanity tears away his fellow creatures from their dearest connections and damns them to the most cruel bondages shall have more votes in a government instituted for protection of the rights of mankind, than the citizen of Pennsylvania or New Jersey who views with a laudable horror so nefarious a practice.” No other opponent of slavery dared to voice his opinions so honestly at the convention.

He eulogized both Washington and Alexander Hamilton.

The US government’s official eulogy for Washington was delivered on December 26, 1799, by Henry Lee, one of the general’s top officers during the Revolutionary War. Morris gave a subsequent oration at New York City’s mourning ceremony on December 31, in which he lauded his old friend’s unshakeable steadiness. “To each desire he had taught the lessons of moderation,” Morris declared. “Never in the public, never in the private hour did she abandon him even for a moment.”

Morris sat at Hamilton’s bedside as the latter lay dying of the wounds sustained in his duel with Aaron Burr. At the funeral, speaking through tears, he delivered a memorable eulogy that encapsulated both his personal reverence for the deceased and his ardent political disagreements with Hamilton, who distrusted republican government and believed authority rightly belonged with society’s most privileged members. “Let it be remembered that nothing human is perfect,” Morris said. “If his opinion was wrong, pardon, oh! pardon that single error, in a life devoted to your service.”

If (like us) you enjoy nerding out on history and want to learn more about this singular American, check out The Constitution’s Penman: Gouverneur Morris and the Creation of America’s Basic Charter, a new release from the University of Kansas Press.