“History isn’t only written by the victors,” quips documentary filmmaker Day al-Mohamed. “It’s also written by the victors who happen to have a historian in their unit.”

In this instance, al-Mohamed is referring to the Battle of Fort Stevens, in which a Confederate army led by Lt. Gen Jubal Early narrowly missed capturing Washington DC during the sweltering summer of 1864. “The Sixth Corps of the Union Army marched in to save the beleaguered city,” says al-Mohamed, “and they actually had their own historian assigned to them. He wrote a fantastic account of how the Sixth Corps saved Washington.”

But that history omitted the pivotal, heroic role played by units of the Veteran Reserve Corps, better known as the Invalid Corps. Composed of amputees and other injured soldiers, these units (deemed unfit for regular combat) were largely relegated to support roles. Their able-bodied brethren treated them with derision and even contempt. But when they unexpectedly came face to face with the enemy at Fort Stevens, representing the Union capital’s last line of defense, the men of the Invalid Corps held Early in check for nearly two full days — just long enough for the Sixth Corps to march in, save the day and claim the glory.

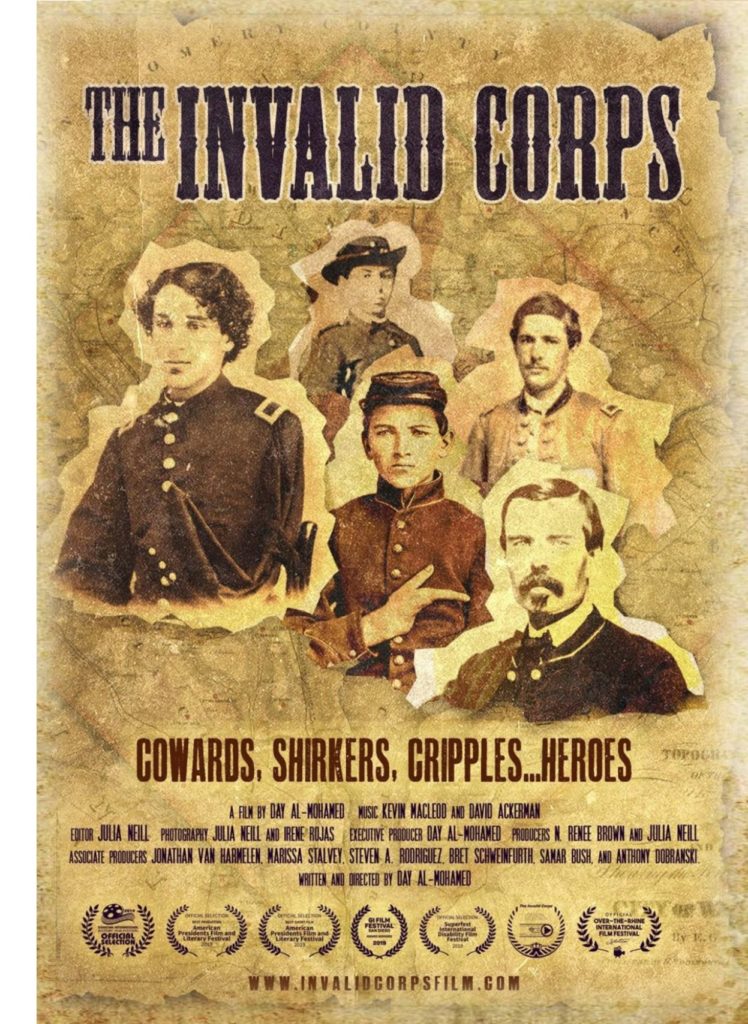

That tale forms the heart of The Invalid Corps, al-Mohamed’s documentary short about the men of the Veteran Reserve Corps. After a successful run on the festival circuit last year, the film is making the rounds of local libraries, universities, and museums, and heading for a possible broadcast date on Maryland Public Television. Its next appearance will be at Millersville University in southeastern Pennsylvania, as part of that institution’s Spring 2020 Disability Film Festival. Contact the filmmakers to line up a screening in your area.

In addition to bringing attention to an untold story, The Invalid Corps is noteworthy for having been produced by an almost 100 percent disabled crew, including al-Mohamed herself (who is blind). We caught up with her last week to get the story behind the film.

How did you come across this story and become interested in it?

My spouse, who is a librarian, happened to come across the sheet music from this song from the Civil War era about the Invalid Corps. And it was making fun of them — about how they were shirkers who were just looking for a way to get out of the actual fighting. So that got me curious. For a song to become popular enough to get published in those days, it must have been tapping into a larger story. It’s even used today by Civil War re-enactor groups — it’s actually a catchy little tune. I wanted to know the story behind it.

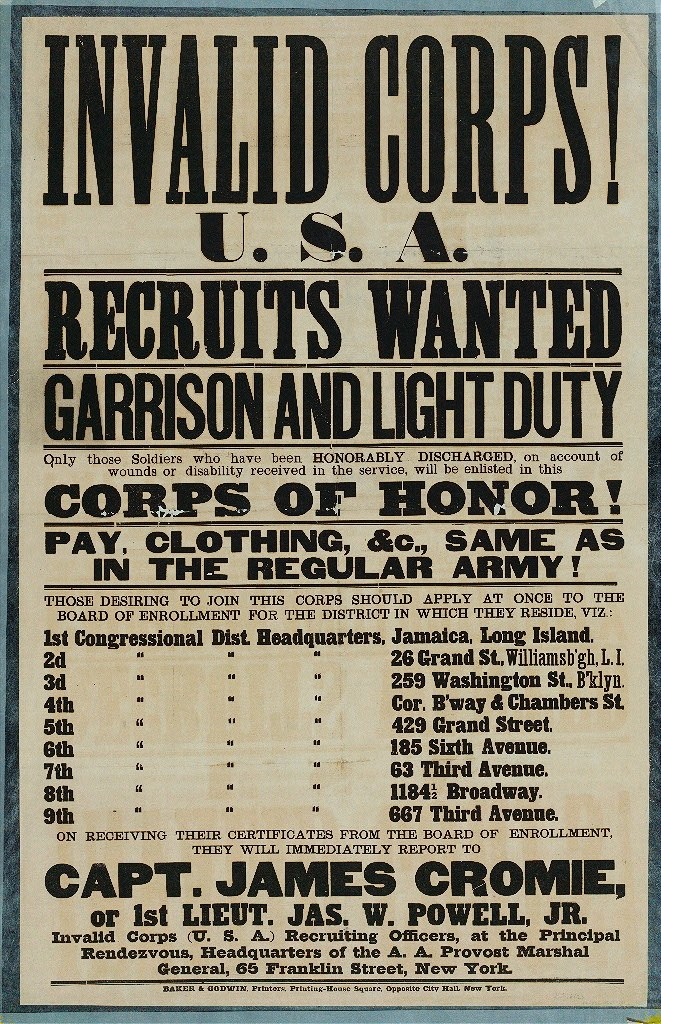

The Invalid Corps was created in 1863, because as the war dragged on there was such a need for manpower that the Union was looking for ways to keep people in the army. And for the soldiers themselves, it was an opportunity. If you went home and you were disabled, what were you going to do there? Whereas if you stayed, you’d be paid as a soldier. Unfortunately, they were treated as second-class soldiers. We called the movie The Invalid Corps because that terminology accurately reflects the way they were spoken about and the way they were perceived. The “Veteran Reserve Corps” is a lot more respectful than the way they were actually treated.

The Invalid Corps got various kinds of assignments. They would protect railroads, work in the prisons, work in the hospitals, perform clerk duty. They also worked as provost’s marshals, or what we would think of today as the military police. Then I started looking at specific units, and I discovered that some of them participated in some amazing action. One of these men, James O’Beirne, played a key role in tracking down John Wilkes Booth after the assassination of President Lincoln. He was also present at the Battle of Fort Stevens.

And what exactly happened there?

General [Ulysses S.] Grant had sent a huge troop concentration to Petersburg in the spring of 1864, and that left Washington DC largely undefended. The Confederates saw an opportunity to catch Washington in a weakened state and inflict some damage.

Jubal Early was the Southern commander, and when his army got to the edge of Washington the only thing standing between him and the city were some units of the Invalid Corps, some 100-day volunteers, some dismounted cavalry, and a bunch of government clerks. Many of them had never been in combat, and some of them had no military training at all.

The men of the Invalid Corps were the most seasoned combat veterans, so they were deployed in the rifle pits out in front of the fort. They were the ones who actually engaged with the enemy. They knew how to organize themselves and take up positions to make it look like there was a stronger defense in place than there actually was. They’d been in firefights before, so they didn’t scare.

The Confederates weren’t sure whether to attack, so they engaged in some skirmishes to test the defense, and they got enough pushback that they hesitated before launching a full-on assault. That hesitation is what gave the reinforcements from Sixth Corps enough time to get there.

What’s the relevance of this story to our current understanding of disability?

We wanted to avoid falling into a standard narrative about disabled people. The typical storyline is about an individual who overcomes setbacks and triumphs over adversity. Sometimes these stories are about sheer survival. It’s not a bad storyline, but we don’t think it really reflects what happened at Fort Stevens. We wanted to give the sense that there is something almost unremarkable about what the Invalid Corps accomplished. They did what soldiers are supposed to do. There was an urgent call to duty, and these men answered the call—able-bodied, disabled, experienced, inexperienced, it didn’t matter. It could have been any other unit doing exactly what they did. They just happened to be the ones this particular duty fell to.

But there was never any recognition of their contribution. There was a song making fun of them, but there wasn’t an account of their actual contributions in the war. And that’s the story we wanted to tell. Despite the name of their unit, these men were not invalids. They were soldiers.