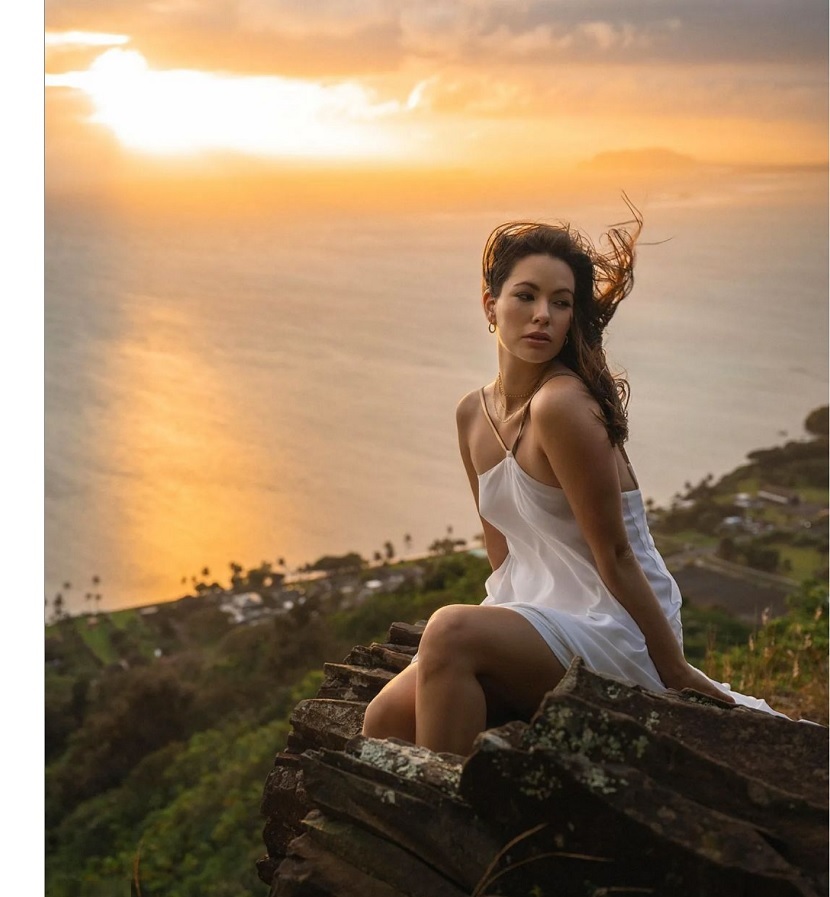

When Shaholly Ayers first tried to break into modeling as an 18-year-old, an agent told her point-blank that her limb difference was disqualifying. “She actually told me I couldn’t model because of my arm,” says Ayers, a congenital right below-elbow amputee. This was some years ago (we’re not saying exactly how many), before models such as Kelly Knox and Mama Cax had started to normalize limb difference in the fashion industry. So Ayers finished college, got an MBA, and developed a successful digital marketing business in Hawaii while picking up modeling jobs (mostly pro bono) on the side.

She was basically invisible until she wasn’t—a lucky break or two got her into Nordstrom’s catalogue, then onto the runway at New York Fashion Week, and then into campaigns for global brands like Hilfiger, Lenovo, and Savage X Fenty. Now Ayers is trying to get her limb-different self a seat at one of the most high-visibility tables in the industry: the cover of Maxim. She’s one of the hopefuls in the 6th annual Maxim Cover Girl competition, vying for a gig that could vault her into the top rank of her profession.

“As far as I’m aware, I’m the only person with a disability in this contest,” Ayers says. “If I were to win it, I think that would be huge for disability. We [people with disabilities] are not really being integrated in modeling, where our limb difference or disability is just another aspect of us, instead of the defining thing. I would like to see that become more commonplace.”

You can help make it happen, because the Maxim Cover Girl winner is chosen via popular ballot. Vote for Ayers at this link. Balloting for the first round started on Monday and runs through next Thursday, June 23. You can vote once a day at no cost; to cast extra votes, you have to pay a few bucks, but the proceeds support a good (and disability-friendly) cause, Homes for Wounded Warriors. The top 20 vote-getters in the initial canvass will advance to the next round, and the balloting will continue all summer as the field gets narrower and narrower. The overall winner will be announced in August.

We talked with Ayers on Monday to get her thoughts about modeling, limb difference, cultural change, and other stuff; our conversation is edited for length. Follow her on Instagram at @shahol1.

How did you become aware of the Maxim Cover Girl contest?

I just happened to come across it on Instagram. They had an ad looking for entrants, so I clicked it and submitted my information. You send in some photos and some basic information about yourself, your Instagram handle and things like that. They emailed me back within a week or so and told me I was part of the contest.

That was very exciting. I couldn’t believe they actually picked me. But I’ve never done anything like this before, and it’s kind of nerve-wracking.

Why is it nerve-wracking?

Popularity contests are not my favorite thing. I’d rather just use my skills and get an answer, either you’ve got the job or you don’t. And this is a long process. At first, 20 of us will be knocked down to 15. Then in the next round it will go down to ten, and then to five, and then one of us will be selected. So it’s gonna be an ongoing thing. People can vote once a day for free, and you also have the option to pay for votes. All of the proceeds from any paid votes go to Homes for Wounded Warriors, which is really cool. But I don’t like asking people to pay for things, so that’s something else that makes it nerve-wracking.

How did you get into modeling originally?

I tried to get into modeling when I was 18, and I kept getting rejected by modeling agencies. And one of the agents said, “You’re never gonna model because you have one arm.” This was years ago, before a lot of the efforts were made toward inclusion. So I just started modeling on my own, networking with photographers and designers, and I got a couple of magazine covers that way. I was doing all of it for free, by the way, but I really liked it. I loved it, actually. It was an artistic outlet, and I liked collaborating with the photographers and makeup artists. So for me, that was fun.

But it got to the point I was spending all this time effort and not really going anywhere. One year I tried out for America’s Next Top Model for like the umpteenth time, and I got as far as the last 20 people, signed the NDA and everything, and then waited and waited and waited but never got the call. It ended up airing on my birthday, and they had shot it in Hawaii, so all of these makeup artists I had worked with were part of the show. I was so angry that I thought, I’m not doing this anymore. So I quit.

What kept you going? Were there any models you knew of who had overcome the bias against disability and succeeded? Did a personal connection give you encouragement to stick with it?

I heard from another model with an upper-limb difference named Debbie van der Putten. She was on Britain’s Missing Top Model, which was one of the first inclusive TV shows for people with a disability. She reached out to me and said they had been using my photos to promote Britain’s Missing Top Model, which I had no idea—and I wasn’t paid for that, either. She thought I was going to be on the show with them because I was on their billboards, and when she didn’t see me in the show she started trying to find me. When she reached me, she told me, “Your pictures were everywhere. You have to keep going. You have to do this.”

So Debbie got me back into it. We went to Los Angeles and networked, and shortly after that I got a booking with Nordstrom. That’s when things started picking up. I walked for New York Fashion Week, and then it just kind of kept going from there.

Between the time you were told to your face, “Someone with your body type is not not qualified to do this work,” to when you started getting offers from Nordstrom—what do you think changed?

Some of it had to do with all that work I had done, doing my own little things for free. I guess I had gotten good enough at modeling to do it, and I had experience on my side. And at that time, there started to be somewhat of a change toward inclusion. It was very small, but it started to happen around that time.

When I had done shoots for magazine covers previously, I was usually told to hide my arm in the photo—to pose so nobody could tell I had one arm. But Nordstrom didn’t do that. They asked me, “How would you wear your jacket? How would you wear this? How would you do that?” They really wanted it to be authentic, which was the first time I ever had that experience. So it felt good to finally be myself in a photo. I didn’t have to hide myself. That, I think, was the most freeing part of it.

Do you think attitudes in the industry have evolved further since you did that first shoot for Nordstrom?

Oh, so much. It’s kind of funny, a lot of times I’ll get booked with younger amputees, and they’ve never experienced rejection because of their disability, at least within the fashion industry. They have more opportunities than I did at 20, and I think that’s a good thing because it shows you how quickly things can change. And the other great thing is, we are being chosen for who we are. I think there’s a bigger push for people with disabilities to have more visibility and be more mainstream. That is definitely good.

But sometimes it’s still hard for me to to wrap my head around. It went full circle from “You can’t do this because you have one arm” to being overbooked because I have one arm.

Has it ever felt exploitative? Previously people focused on your arm as a matter of exclusion—did it ever feel like they were still focused on your limb difference, but in the opposite direction?

Maybe for a short moment, but it didn’t last. Because people were always very sensitive to getting the representation right. After Nordstrom, every production team I worked with would talk to me a lot about how to approach the photo shoot and get it right. So I did feel like there was a lot of effort being made.

That runway show during my first New York Fashion Week was also huge for inclusion. Our pictures were published around the world, so it got my little arm out there. Not really my face, though. That was actually kind of funny. The designer I walked for was very avant garde, so I had a full face mask with my dress. I was painted silver and everything. So you can’t see my face, but my arm was in every magazine.

What sort of changes would you like to see going forward?

When I started, I thought I would just fit in as one of the models. I never imagined there would be a separate “disability” segment. Ideally, we just want to be included like any other model. I don’t want to be the disabled model for the disabled group, which I feel is kind of what’s happening. We’re not really being integrated, where we’re just considered one of the models, and our limb difference or disability is just another aspect of us instead of the defining thing. I would like to see that become more commonplace.

Do you see the Maxim contest as a potential means to tearing those barriers down a little further?

I think so. As far as I’m aware, I’m the only person with a disability in this contest. So I’m going against able-bodied people, and if I were to win it, I think that would be huge for disability.