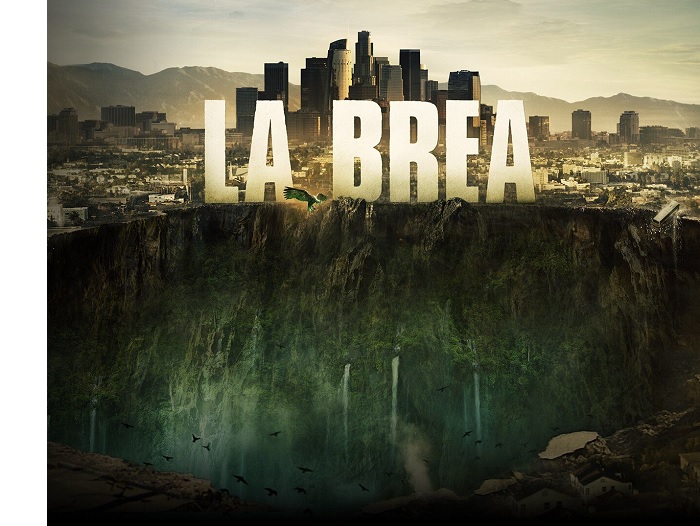

NBC’s new series La Brea tackles limb loss within the first 30 seconds of Episode 1. The intro music is still fading out when a teenage character named Josh asks his sister, Izzy: “You’re single-, not multi-axis, right?” She’s a below-knee amputee, and he’s cynically using her disability as the theme of his college essay, hoping to come across as a serious person. Things get kinda serious for the whole family about 30 seconds later, when Wilshire Boulevard suddenly parts like the Red Sea and swallows up 10 or 15 square blocks of midtown LA. Josh gets sucked into the vortex, followed closely by the kids’ mother; Izzy manages to stay at street level, becoming a de facto first responder to an unimaginable disaster.

She also becomes the first primary character on a network series to have a limb difference. That alone would make Izzy noteworthy, but it gets better: The part is actually played by a limb-different actor, 19-year-old Zyra Gorecki. In her only previous network appearance, a lone episode of Chicago Fire five years ago, Gorecki played the kind of role amputees have typically been boxed into—an accident victim. But she brings a lot more to La Brea than shock value. Her character is part of the emotional core of the series, a whole human whose limb difference is largely incidental.

“I think people can relate to La Brea especially after the pandemic, because there’s a lot of times in the show where you feel completely helpless and hopeless,” Gorecki told the Chicago Sun-Times earlier this week. “You’re in this crazy storm, and you are holding onto whatever you can find and hoping that you survive.” A similar type of upheaval often accompanies limb loss, making Zorecki (who lost her left leg in an accident at age 13) a particularly good fit for the role of Izzy.

La Brea airs Tuesdays at 9 pm Eastern. We caught up with Gorecki on the eve of the show’s broadcast premiere. Our conversation is lightly edited for continuity and clarity.

Hair and Styling: Stefani Pappas.

Makeup: Kira Netzke.

Representation: Bravo Talent Management.

Can you tell me a little bit about your character?

I play Izzy. She is the daughter of the family that you see torn apart when the sinkhole opens up—my mother and my brother both fall into the sinkhole, and it’s up to my dad and I to bring them back. She’s actually a really, really cool character. Not only is she, you know, a badass that get stuff done. But she’s also just a regular kid who is going through regular kid stuff. Limb difference is not her only character trait. She has a whole personality, and I think that’s really important.

Was Izzy conceived as an amputee from the start, or did the show producers modify the character after you got the role to reflect the fact that you have a visible limb difference?

This made me really happy. The writer of the show is David Applebaum, and he actually wrote the character as an amputee. Then he reached out to an actor named David Harrell [who is an upper-limb amputee] and asked, “Do you know anybody that would possibly fit this role?” David’s involved in the same limb-different camp as I am, and he sent out an email to all the other campers. I sent the email to my agent and said, “What do you think about this?” I sent in an audition [tape] and they told me, “[Izzy doesn’t] hate her family, so you can be nice.” So I got a second audition and I was a little bit nicer, and they told me: “All right, you’re coming out to LA for a chemistry read.”

So this was like a golden opportunity. I’ve talked to various actors who’ve always dreamed about getting a role of this type.

Oh, yeah. Absolutely. I had been trying to get my foot in the door and push my career forward, so for this to come around was absolutely nuts. It was very surreal. At first I thought, “You’re joking.” And then I got on set and I thought, “You’re not joking.”

Was acting always an ambition of yours?

Not at all. I got my leg cut off at 13, and I decided I wanted to “inspire” people—which now makes me cringe so much, but that’s what I was thinking at the time. So I decided I would be a model, because I’m six feet tall. I sought out an agent [Bravo Talent Management], and she just kept sending me out on acting things. Apparently she thought I had the right personality for that, and she’d send me on these casting calls to get me in front of these directors. And I used to get so sick before every audition. I was absolutely terrified—so nervous. It was awful.

So you weren’t one of those theater kids who was in every school play?

Not at all. I have terrible stage fright. The thought of going onto a stage makes me want to vomit. But being on set is a totally different feeling. That’s super fun. My first TV role, which was Chicago Fire, was only a two-day shoot, a super-small role—I just screamed—but I got bit by the bug. At that point I decided, “Yep. This is this is what I want to do. I want to be an actor.”

You just screamed? What was the role?

I was a struck pedestrian. I was in an accident and my leg snapped sideways, and they had to have an amputee for the role. [The paramedics] would snap my leg back into place, and I would scream.

So you’ve advanced from a bad cliche of amputee roles in Chicago Fire to this sort of dream role in La Brea.

Pretty much. For La Brea they wanted an amputee who was a whole person, not just a fake leg to bring on set.

Did you recognize how unusual that was before you went out to do the read, before you got the role? Or was it something that kind of dawned on you as you went through the shoot?

I’m pretty sure at first I didn’t know what was happening. It was kind of like being thrown into a whirlpool and trying to swim. But I started realizing that this is a really big chance to educate people about limb difference. That was happening even on set. That’s when I started to realize how much change I can make in this role.

So if your initial goal in becoming a model was to inspire people, but you now look back on that and cringe—what sort of influence would you like to be able to have as an actor?

What I want the most from all of this is for amputees to be able to walk down the street and not be seen as this freak that people just stare at. I want amputees to be seen as people—as human beings with emotions. And I want to teach amputees that it’s okay to be the way you are, because you are absolutely amazing exactly the way you are, and you don’t ever have to be ashamed.

Hair and Styling: Stefani Pappas.

Makeup: Kira Netzke.

Representation: Bravo Talent Management.

How did you come to that knowledge yourself? Did you already intuitively understand that, or was it something you had to learn?

We had a lot of trauma happen in my family when I was growing up. I was very close to my grandpa, and he died of lung cancer when I was 11. My other grandpa was living with us for three and a half years, and he was dying of COPD and cancer. Two months after my grandpa died of lung cancer, my mom got breast cancer. And then two months after she was clear of cancer, I had my leg amputated. So I’d already seen my family deal with those kind of things. And mom has been—she is crazy, first of all. But not crazy in a bad way; she’s crazy in the coolest way possible. She has never been insecure. She has always raised my sister and I with confidence and security in ourselves. So after having my leg cut off, I never thought of myself as different. People would say to me, “Oh you’re so beautiful even though you have a fake leg.” And that really made no sense to me, because all of my beauty was not stored in my ankle and a few inches of leg. It really doesn’t affect anything about who you are.

But as you know, a lot of people struggle with that emotional transition.

I think in society these days it’s very, very hard to love yourself. You have to make the conscious choice to do so. And it’s even harder when you have all these people saying, “You’re ugly because you don’t have a foot, you’re ugly because you look different than I do.” Especially on social media.

Is there a sense in which your message of self-acceptance transcends amputees? Do you feel as if a character like Izzy could influence not only people with limb difference, but people with other kinds of differences?

I really hope so. I have a story about that. There’s another amputee from my [home]town who’s congenital. And they have three little sisters, and when the little girls got old enough to realize that people were staring at their brother, it would make them so mad. The oldest one would say, “Why do they have to stare?” And their mom took her aside and said, “If you saw a car in town and there was a unicorn in the back, would you stare?” “Probably.” It’s the same thing with limb difference, or any kind of difference. We’re just a bunch of magical unicorns.

Do you think there are echoes between the premise of La Brea and the experience of limb loss? You’re just going about your business, living your life, and then this radical change occurs and suddenly you’re in a totally different world. You almost have to reinvent yourself.

That’s actually a really interesting way to think about things. Because you’re very correct: For the average amputee, it’s either sink or swim. You either figure it out, or you will sink. I think that’s the same in La Brea. It’s about survival.