Coretta Scott King, John Lewis

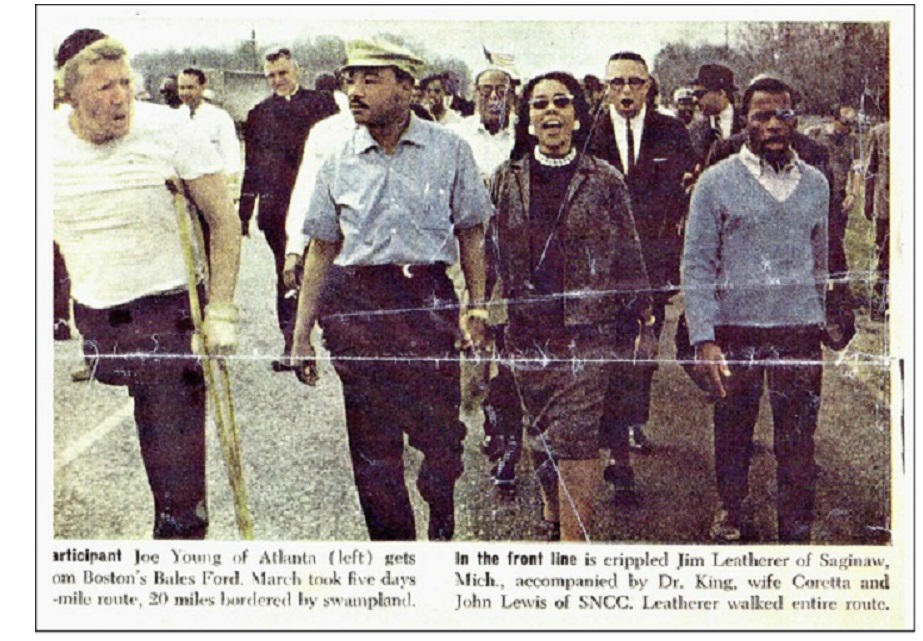

We haven’t figured out how Martin Luther King Jr. first got acquainted with Jim Letherer. It’s possible they never met until March 21, 1965, when King and several thousand marchers left Selma, Alabama, en route to the state capitol in Montgomery. Letherer was one of the 3,000, and the only leg amputee in the crowd. By a judge’s order, only 300 demonstrators were permitted to walk the entire 54 miles to Montgomery, and only 50 of those 300 slots were allotted to non-Alabama residents. The 31-year-old Letherer, who lived in Michigan, was chosen as one of the 50.

He became one of the most remarked-upon figures of the four-day protest march, which came two weeks after the infamous Bloody Sunday crackdown at the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Walking the entire 54 miles on crutches, Letherer was targeted by hecklers, lauded by fellow protestors, immortalized in song by Pete Seeger, and singled out in the press as a symbol of the marchers’ determination and courage.

“You see the world through a different perspective when you see it from a wheelchair or on a pair of crutches,” he told one reporter. “You look for things that happen to the underdogs, the long shots, those who have to beat the odds just to get the little things that other people take for granted.”

How Letherer came to receive one of those 50 precious out-of-state invites is a matter of conjecture. If he’d already established his Civil Rights bona fides prior to the march, we can find no record of it. He did possess some social-justice cred as a settlement house worker, so perhaps he was known to movement leaders on that basis. Or maybe he simply inspired King and the other organizers through sheer conviction—if a guy insists on crutching 50-plus miles to advocate for your cause, how can you say no?

Lest we lose sight of the cause to which Letherer was so deeply committed: Lowndes County, the site of much of the march, had roughly 8,000 Black citizens in 1965. Not a single one was registered to vote. Nor would they be until after passage of the Voting Rights Act later that year.

Whatever Letherer’s reputation as a Civil Rights activist prior to Selma-Montgomery, he became a high-profile ally afterward. When he was arrested at a sit-in in Chicago three months later, the New York Times identified him as a representative of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The following year, Letherer joined King and James Meredith in Mississippi for the March Against Fear. And in 1967, he received a personal invitation from King to participate in a December march. Letherer wrote back: “This old body of mine is tired and worn. The door is not closed yet as there is a little time left and I am trying to put a few things together in the hopes of doing it. Love and Freedom, Jim. . . . P.S., Merry Christmas to the CIA man reading your mail also.”

Nearly 20 year later, Letherer—who’d lost his right leg to childhood cancer in the early 1940s—made headlines again when he embarked on a cross-country trek to raise funds for cancer research. But it was during those four days in 1965 that he made his indelible mark. Two life-sized statues commemorate his one-legged, 54-mile march—one at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta; the other in White Hall, Alabama, at the midway point between Selma and Montgomery. Letherer also shows up in Lynda Blackmon Lowery’s 2015 memoir, Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom. Lowery, whose 15th birthday fell on the second day of the march, panicked when federal Guardsmen appeared along the route. They were there to protect the marchers, but Lowery—who still had 35 stitches in her head after being clubbed by Alabama state troopers on Bloody Sunday—was understandably terror-stricken at the sight of the soldiers, bringing the entire march to a halt. “Jim Letherer said before he let anybody else harm another hair on my head, he would lay down and die for me,” she later remembered. “And I said, ‘I can’t let him do more for me than I was willing to do for myself.'”

The willingness to do for others, and for each other, is a big part of what we celebrate on Martin Luther King Day. Jim Letherer, who died in 2001, is well worth celebrating this week, too.