As Hugh Boyle entered his local CVS, the greeter pulled him aside and whispered: “Oh my god, did you hear what that guy just said about you?”

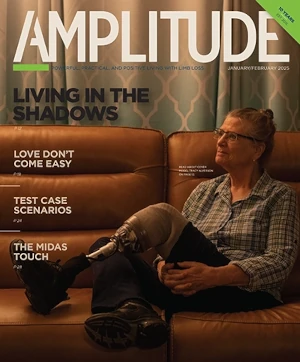

Boyle had a fair idea that it wasn’t a compliment. “That guy” was a young, fit, nondisabled dude who’d pulled his muscle car into a disabled parking spot alongside Boyle, a below-knee amputee in his 50s who’d parked in a regular spot.

“I wound down my window and said, ‘What are you doing? That’s a disabled spot,'” recalls Boyle. The driver responded that he was in a hurry and didn’t give a sh*t, and Boyle called him out on his rudeness. “I said, ‘F that, look at me. If I’m not parking there, you don’t need to park there.'” Curses were exchanged, and the offending driver stomped off spewing bile over his shoulder.

Boyle locked his car and made his way toward the store, reaching the entrance a few paces behind his antagonist. “The greeter there knows me, as I’m at that store all the time,” Boyle continues. “She’s very sweet, a middle-aged Indian woman. She leaned toward me and said, in a very low voice: ‘He called you a f’ing one-legged punk.‘”

Boyle was less than a year out from his amputation at that time. He had only owned a prosthesis for a few months and was still learning to walk on it, and he hadn’t resumed driving until a few weeks prior to the incident. The trip to CVS—to pick up a prescription for his sick daughter—was just the second time he’d driven himself on an errand.

In short, he was still adapting to life with limb loss and understanding what it meant for his identity. It wasn’t necessarily an ideal time to get slurred by a clueless jerk. But as Boyle came out of the pharmacy, he didn’t feel wounded by the encounter. Quite the opposite.

“I felt empowered by it,” he says. “I felt empowered by saying my piece.” Far from undermining his sense of self, the confrontation gave Boyle a jolt of confidence that life’s routines—even the messy, ugly, imperfect ones—would continue as normal, and that he would continue to be the same person he’d always been.

His only regret was that the good-hearted greeter had been caught in the middle and was obligated to repeat the muscle-head’s nasty words. “It felt so wrong for her to have to say that,” he laughs. But as he departed the store, Boyle assured her everything was fine. “He’s just given me a great idea for a T-shirt,” he told her.

And so was born Amputee Punk, Boyle’s line of shirts, hats, mugs, and other merchandise “for amputees with attitude.” He launched the storefront earlier this year as a complement to his main gig as the co-principal of Doable, a creative services agency that’s staffed primarily by disabled talent.

A lifelong advertising professional who has worked for high-profile national and international brands, Boyle instantly recognized the brand value of the would-be insult. “Fifteen percent of disabled people in full-time employment conceal their disability because they feel it would be bad for their careers,” he says. “We’re not self-identifying with pride, and we should be. But I don’t want to self-identify as just an amputee, because I’m more than that. I want to assimilate my limb loss into my overall identity.”

That’s why Amputee Punk offers variations for a wide range of personal tastes and predilections. If you’re an amputee cowboy, a death-metal amputee, an emo amputee, a hip-hop amputee, or anything else, Punk is there for you.

Boyle’s target audience—”amputees with attitude”— feels like an ideal fit for Amplitude‘s readership. So we’re teaming up with Amputee Punk for a special promotion: Buy an Amplitude print subscription ($15 for six issues/one year) and get a 20 percent discount on all Amputee Punk merchandise. The offer is good throughout the month of May.

We’ll leave you with this thought from Marky Ramone, who knows a thing or two about punks: “Punk rock is being honest, believing in yourself, and doing what you gotta do.” It’s a pretty good formula for living well with limb loss, too.