Disability employment challenges are so far-reaching that we spend a whole month talking about them.

By Diana Theobald

I was laid off from my job earlier this year. I’m in great company, though. With financial indicators pointing toward a recession, corporations have been competing to cut costs. This means ruthlessly laying off as many people as possible before the next budget cycle begins.

As an unemployed person with a disability, I’m in even greater company—so great that we spend all of October talking about it. Welcome to National Disability Employment Awareness Month (NDEAM, for short).

NDEAM is technically the only nationally recognized month for people with disabilities in the United States. Sure, there’s Disability Pride Month in July, but that’s a grassroots designation that the federal government has yet to formally acknowledge. The employment disparity between people with disabilities and people without is so great, however, that the feds not only acknowledge us, they set aside a month to focus on us. Not a day, not a week. A whole month.

Even one month doesn’t feel long enough when you’re in the job market—or in the workforce—with a disability. I’ve been acutely aware of disability employment for more than 100 months now. The streak began immediately after my amputation. Lying there in the hospital, I had a professional identity crisis. In my seven years of working in the entertainment industry, I had never seen anyone with a visible disability. In my post-amputation haze, I couldn’t visualize myself as both an amputee and an executive, especially not in the entertainment business. Would I be able to keep moving forward on my chosen career path? How does one do that on one leg?

I was short on guidance, and so was everyone around me. Because none of us had ever worked alongside a person with a disability.

Prep Your Coworkers

When you experience a trauma, there are generally resources available to help you adapt and move beyond the incident. There are often resources to help your loved ones, too. But there was nothing to help my coworkers adapt to my limb loss after my accident.

Coworkers inhabit a strange space. You spend most of your day with them, but they’re distanced from your personal life. When I had my accident, only the members of my immediate team were fully informed about my injuries. The rest of the office signed a massive get-well-soon card, but nobody told them exactly why they were signing it. The story was that I’d broken my ankle.

So when I returned to the office six months later, crutching in on one leg, everyone who had signed the card was shocked and horrified. My boss hadn’t shared the news of my amputation beyond our team; he figured it wasn’t his news to share. But he didn’t anticipate the awful position he left me in. I had to experience everyone’s immediate reaction to my trauma in real time. People cried. It was awful. I don’t know that there’s a good way to share sad things at work, but I wish my company had worked with me to find one.

Very little about my return to the office went smoothly. After they recovered from their initial shock, my colleagues wanted to get right back to how we worked before. But I couldn’t do the job exactly the way I had before I acquired my disability. The basic mechanics of the job were mostly unchanged—I did the bulk of my work on my laptop—and the office manager was quick to work with me on accommodations. He ensured I had a dedicated parking spot and could access my desk, the bathroom, the kitchen, the conference room—anywhere I needed to be within the office environment.

But that didn’t help if I had to leave the office for meetings, off-site reviews, or recording sessions, which happened regularly. My coworkers liked to work through problems by getting everybody outside to walk around, just for the change of scenery. But the route wasn’t wheelchair-accessible, and I wasn’t strong enough at that point to keep up with them on foot. Their “accommodation” was to continue taking group walks without me, with the promise to fill me in afterward. That made me feel useless.

Things got worse when a medical setback took away my ability to drive for seven months, leaving me trapped like Rapunzel in my inaccessible apartment building. I couldn’t afford to Uber to work every day, and my job declined to help with the costs. They also couldn’t fathom doing virtual meetings—this was back in 2016, long before the pandemic. The accommodation they came up with was to allow me to do whatever work I could from home, while my teammates covered my in-person responsibilities.

It seems strange to complain that I got paid to sit on my couch and only do half my job, but I was miserable. The fact that my coworkers were having to work harder to cover for me made it even worse.

Most people don’t realize that accommodating an employee with a disability involves way more than the physical building and the tools of the job. Truly accommodating someone might require a whole unit, maybe even the whole company, to change the way they work. And it became pretty clear my old company wasn’t willing or able to make those types of adaptations.

So I found another job with teammates who were willing to truly accommodate me, to the point that I could fully do my job. (It even paid better!) The situation wasn’t perfect—I think most people would not recommend starting a new job in between surgeries while sporting a Taylor Spatial Frame and a PICC line. But as my new coworkers pushed my wheelchair from meeting to meeting at San Diego Comic-Con, ensuring every location they went to included me, I felt unbelievably valued.

Unfortunately, a few months after I started, our parent company bought a studio that did what my division did, only better. Just one week after my final surgery, I was laid off.

Working the Network

When I first got into the workforce, everyone said I had to network, but I didn’t know how. The breakthrough came when I heard an alum say, “Networking is just making friends.” Mind. Blown. I know how to make friends!

I spent my early career making friends all over the entertainment industry. I went out for drinks with coworkers and my counterparts at other companies. I joined some professional organizations. I volunteered at events (pro tip: Everyone has to talk to the check-in person). I planned panels, which gave me an excuse to reach out to higher-ups. Over time I developed a strong network, and all these people were moved by my accident. Many reached out to say, “If there’s anything I can do, let me know.”

I took them up on the offer when I was back on the job market about a year after my amputation. And, true to their word, the people in my network stepped up. They helped me arrange everything from informal meetings to bona fide job interviews. It worked exactly the way job hunting through your network is supposed to: Leverage your personal connections to increase your career opportunities. But post-limb-loss, the personal aspect of this became a problem. Everyone I met knew I’d recently lost a leg, and they all wanted to talk about it. And that was hard. It brought up emotions, and you can’t get emotional in a job interview. I tried to walk the tightrope between the professional and the personal, but it’s hard to balance on one leg.

I ended up finding the perfect job on Indeed. The office was in Atlanta, a continent away from me in Los Angeles, and the team didn’t know me at all. The first few interviews took place over the phone, so my physical appearance didn’t distract them. It was just pure me, and wouldn’t you know, I got the job. Along the way, there were a couple of in-person interviews to finalize the process, and for those sessions I did something I’d never done before: I intentionally hid my disability.

Being able to hide what marginalizes me is an enormous privilege. I have complicated feelings about it now, but at the time it felt like a no-brainer. It felt like my prosthetic leg was getting in the way of my career, and I wanted to get this job by any means necessary. I had built back to a pretty fluid walking gait, and with the right outfit, most people couldn’t tell I was an amputee. So I decided to conceal it for as long as I could.

It was a bad idea. The company flew me out to Atlanta and put me up in a hotel for my first week of work, but because they didn’t know I was disabled, they put me in a regular room. I tried to pull a switcheroo at the hotel, but every accessible room was booked. I asked the front desk to at least help me find a way to shower—a chair or bench or something—but the best they could do was give me the key to an accessible room in another hotel. I couldn’t stay in that hotel, though; I could only shower there. On my first day at my new job, I got up extra early, gathered all my stuff, left my hotel, went to another hotel, and showered and got ready. Absurd.

Awareness Begins With Openness

I couldn’t hide the truth for very long. My new coworkers noticed me limping on my very first day, so I lifted my pant leg to show them why. My boss quickly figured it out, too, but he embraced the task of learning to manage an employee with a disability. It was a learning experience for me, too—I didn’t know how to manage me, either.

The keys to making it work were trust, vulnerability, patience, and honest self-reflection. For example, I struggle to get to work on time. It was a struggle before I lost a leg; losing a leg made it worse. I brought this up to my boss, and he said that didn’t matter to him—I could do my job anytime, anywhere. But he also pointed out that other employees might notice my chronic tardiness, and he suggested that I work a little later to make up for any time I missed in the morning. I was already typically the last one to leave the office, so that worked fine.

In that same conversation, he said I could work remotely two days a week. That was a revelation back in 2017.

Just as my boss had to be patient with me, sometimes I had to be patient with him. About two years into my tenure, when he was writing a job posting for a new executive assistant, he called me into his office.

“Can I say they need to be able to lift 50 pounds?” he asked.

We’d developed a candid relationship by then, so I didn’t hold back. “Why in the world does your assistant need to lift 50 pounds?” I asked.

“For pizza parties,” he responded. “They have to carry the food up.”

“Your last assistant used a cart for that.”

“OK. Well, they might also need to move a box of files.”

“What files? Isn’t everything digital now?”

My boss looked exasperated. “There are still paper files!”

I took a deep breath. “I don’t know the law exactly, but it seems to me if a job genuinely requires a certain level of physical ability, then it’s fair to include that in the description. I think it’s ridiculous to suggest that this job would require that level of physical ability. But you know your needs best.”

I don’t think he included that requirement in the job listing, but the person he ended up hiring could probably lift 50 pounds anyway. She still used the cart for pizza parties, though.

As silly as it might seem, this open dialogue was what made that job great. When people talk about bringing their whole selves to work, they’re talking about what I had. My boss encouraged me to embrace my disability and use it as a value-add for our team. He even connected me with the company’s disability business resource group (BRG), also known as an employee resource group (ERG) at many firms. I had joined the disability BRG in my previous job, but that committee had been focused on parents of children with disabilities. This one was actually focused on disabled employees—so novel. I dove right in, joining the board, planning events, and raising our company’s awareness about disability employment—in October, and in every other month.

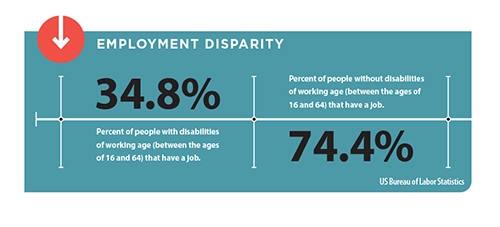

By the end of 2019, advocating for disability inclusion through the disability BRG had become more interesting to me than my day job. My boss helped me transition into a full-time position as a diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) specialist. Working in DEI was dynamic, challenging, and fulfilling, but often frustrating. The more you learn about the employment headwinds facing people with disabilities, the more daunting it can seem. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 34.8 percent of people with disabilities of working age (between the ages of 16 and 64) have a job. Compare that to 74.4 percent of the same age group without disabilities. Women with disabilities are more likely to be unemployed than men with disabilities, and Black people with disabilities are four times as likely to be unemployed as White people without disabilities. Disability takes the same inequities we find in the nondisabled population and increases them, sometimes exponentially.

My work in DEI often felt too rewarding to be true. Turns out it was. At the start of this year my new boss and a sizeable chunk of our department were laid off. Including me. This year marks the first since I acquired my disability that I’ll likely be spending NDEAM without a full-time job. But now that I’ve felt the joy of bringing my whole self to work, I want to continue to help creating that for other people. Because my experiences working with a disability aren’t unique. I can speak personally to the obstacles I’ve encountered—physical and emotional—and lessen them for the next person.

I’ll be paying attention to how companies join this conversation. For ideas about how you can participate yourself, check out the US Department of Labor’s 31 Days of NDEAM.

Diana Theobald is a freelance writer and diversity consultant. She has held roles in creative development and diversity & inclusion at Warner Bros. Discovery, Marvel, DreamWorks Animation, and NBCUniversal.