Amputees Confront the Causes of Their Limb Loss

By Élan young

Losing a limb, particularly from trauma, can be such a painful experience that the activity that led to the amputation can forever be a difficult reminder, if not a full-blown emotional trigger. Sometimes, however, in the aftermath of trauma and rehabilitation, an amputee decides to return to the same activity that led to his or her amputation. There is no right or wrong way to approach returning to an activity connected with an injury, but for those who do, there is a common thread. Everyone has to make his or her own adjustments and overcome fear. Three individuals who returned to activities that led to their amputations shared their experiences with Amplitude.

In January 2007, Amy McCraken was thrown from her horse, who was green and young, and who had pent-up energy from not being turned out because of bad weather. The horse bucked her and she went flying, landing on her feet. The force of blunt impact shattered her ankle. Her right tibia and fibula were broken in three places each.

Over the course of eight years, McCraken had 18 surgeries, four external fixators, a staph infection, PICC lines, vacuum-assisted wound closure therapies, and more. She spent nearly five of those eight years wearing casts and hobbling on crutches or in walking casts. Each surgery had a minimum of three months’ recovery. Amazingly, McCraken rode and competed in horse shows throughout those years, even putting doctors off during the summer months so she could compete before the next surgery. “I would ride with the cast on or when an incision would heal,” she recalls. “My part was to learn how to stay balanced and communicate a little differently with the horses.”

Part of the reason McCraken felt compelled to continue horseback riding was that she had just started riding two years before the accident. “I always loved horses and knew that if I didn’t ride now I’d regret it on my deathbed,” she says. In 2014, she finally opted for an amputation of her right leg just below the knee.

“After I lost my leg, I got back up on the horse with my check socket for the first time, and after a trip around the arena I was terrified,” she says. Her prosthesis was bulky and prevented her from being able to feel in control. It also tended to poke the horse in places where the horse would not anticipate contact, which could be dangerous. “I was terrified that if I came off the horse, the prosthesis and impact from a fall could break what little is left of my lower leg/knee, and I would become an above-knee amputee.” So, she followed her instincts and got off the horse, took off the prosthesis and the stirrup on the right side, and got on again. “When I got back on, I was not afraid. It was one of those magical happy moments, and I knew I could ride and compete again,” she says. This kept her training and competing, and any fear melted away.

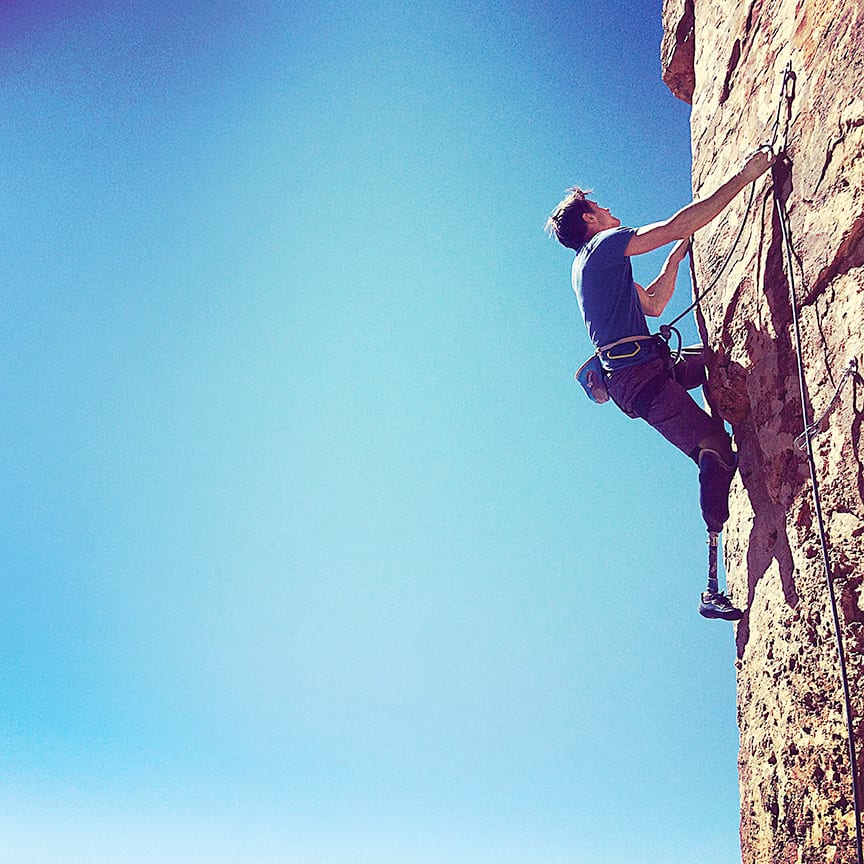

Craig DeMartino, Rock Climbing

In 2002, Craig DeMartino was climbing in Colorado when a miscommunication with his climbing partner led to a 100-ft. fall, or roughly the height of a ten-story building. That he survived the impact is nothing short of a miracle, but he was not out of the woods for some time to follow. First he had a three-month stay in the hospital then in a rehabilitation facility where he began his recovery. Eighteen months after the surgery, he went from hospital bed to wheelchair to walking boot. Nevertheless, he did not see enough healing to enable him to live an active and pain-free life again, so he opted to have his leg amputated below the knee. This difficult decision turned out to be the key to regaining his quality of life.

The decision to climb again came from watching his wife and friends go climbing. “It was something I loved, but after being hurt so badly, and with a fused back and neck, I was worried about getting hurt again,” he remembers. “But when I would think about climbing it made me want to go back and at least try—to make the choice instead of the accident making that choice for me.”

As he eased back into the sport, he battled fear for the first year. “I kept thinking I would get hurt and the fear took a long time to get under control,” he says. “There were a lot of setbacks. But with doing it over and over, it got better.”

Of course, with such extensive injuries, the challenge wasn’t just mental. DeMartino also had to learn to use his new body, which didn’t work the way it used to. He had to relearn almost everything. “I measured gains in inches, and figured it would take a long time to get anywhere with climbing,” he says. “I came up with a list of climbs I wanted to redo and that became my focus.” He still makes climbing lists to motivate himself. Moving at this deliberate pace allowed him to build up to the climber he used to be. “Now, though, I [have] such a better appreciation for climbing and being alive and outside with my family,” he says. “I feel like a much better climber.”

Ursula Wachowiak, Motorcycling

Ursula Wachowiak was headed to her first Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in July 2013 when she was hit by an oncoming driver who was attempting to pass a semi-truck in a curve. She was to the right of her lane, so the bulk of the damage she sustained was on the left side of her body.

When she woke from a four-day medically induced coma, she was given surgical options for her left leg, which had been severely damaged. Her choice was to have the leg amputated below the knee. During the next two weeks in the hospital, she wondered if she’d be able to ride again.

“Mentally I was in a very bad place, and not knowing if I could physically drive a motorcycle again beat me up pretty badly,” she recalls. Riding has since become synonymous with living. “Riding is almost like waking up for me,” she says.

The first time she got back on a bike after the accident was as a passenger. She had stopped at a Harley-Davidson dealer with a friend, and when she entered the dealership in her wheelchair, she saw all the bikes and instantly burst into tears. “I left my friend to shop and went back outside to sit in my misery,” Wachowiak recalls. “When she came out to find me, I sobbed and let loose a dozen ‘What ifs?’ and ‘Why mes?’”

In that moment, her friend saw an opportunity. There were two men in the parking lot next to their motorcycles, and she walked over to them. She told them about Wachowiak’s incident and the sadness she was going through. “One of the men agreed to give me a ride around the parking lot,” she recalls. “I loved it, but I was not in control; it was a little scary.”

The first time Wachowiak drove a motorcycle was eight months after her amputation and several other surgeries. While visiting Charleston, South Carolina, she met up for lunch with a Facebook follower and fellow amputee motorcyclist. The man and his wife then invited her to their home where he brought out his motorcycle and told her to get on. “I wasn’t sure this was a good idea because, after all, motorcycles are heavy, and I was just getting the hang of walking,” she says. However, she says she felt like a child at Christmas, so she got on the bike.

After she feathered the clutch and made the bike rock, the man said, “Go!” “Oh, man, was I scared,” she remembers. “He told me how he shifted with his missing leg, but I had no idea how I would turn or how I would come to a stop, or if I would pee my pants the second I started rolling.” Off she went, down the street for a mile and then turned around and came back wearing a big smile.

Wachowiak eventually got stronger, learned how to function with the prosthesis, and learned about the mechanics of riding from amputee support groups online. She experienced being able to ride again with only minor adjustments, aided by her new outlook and the fact that below-knee amputees still have a center of balance to work with.

Returning to the road has not been without fear, though. While she has always been a safe motorcycle driver, she found that she was constantly nervous. She would often sweat, white-knuckle the grips, and slow dramatically in curves. “I have had a few close calls with irresponsible drivers since my incident, and that sure doesn’t help,” she says. Yet she persists in the pursuit of her joy. “There is no cure for fear, only the strength to persevere or to know when to quit. I continue to ride and persevere and today I am pretty good at outrunning most of the demons.”