How can amputees get better sleep? The lack of solid research leaves everyone in the dark.

By Chris Prange-Morgan

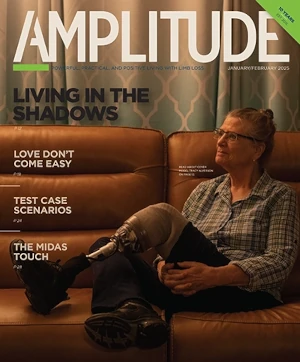

When Tricia Hines had her below-knee amputation in 2013, she breathed a sigh of relief. After many years of dealing with chronic, incapacitating ankle pain, she could finally move on.

“I injured my ankle from overuse in sports during my younger years,” says Hines, a ski instructor who lives in Utah. “After ten surgeries, including a fusion and attempted ankle replacement, amputation was absolutely the right thing to do.”

About four years after her amputation, however, Hines began suffering from unbearable nighttime phantom limb pain. “It was like this irritating buzzing sensation that only happened when I wasn’t weight bearing,” she says. “It woke me up in the middle of the night, and I couldn’t sleep. That lack of sleep began to impact every area of my life—my daytime activities, my job, my mental health. I knew I needed to do something about it, or I’d completely lose my mind.”

Knowing what to do wasn’t easy, though. As Hines discovered, there is hardly any medical research on the topic of sleep in the limb loss community. Recent studies in the general population have documented sleep’s profound influence on human health. It’s well known that lack of sleep is associated with a wide range of physical and mental ailments. We also know that sleep deprivation often coincides with chronic pain and stress, so it makes sense that people with limb loss face hurdles to getting good sleep. But we still don’t have a detailed, scientifically validated understanding of how limb loss interferes with sleep, how poor sleep affects amputees’ health, and what strategies amputees can use to get better sleep to support their overall well-being.

“It’s no secret that the limb-loss community as a whole struggles with higher amounts of anxiety, PTSD, and depression,” says Melissa DeChellis, a below-knee amputee and founder of Adaptively Abled Amputees. “It’s not rocket science. I’m a research geek myself, so it surprises me that the area of sleep hasn’t been studied more with this population, since many of us deal with all of these things in addition to musculoskeletal or neuropathic pain, financial struggles, and insurance hassles.”

“Most people who don’t understand limb loss have no idea how much extra effort goes into our everyday lives just to keep up and function,” adds Kristin Hocker, a PR professional, single mom, and high above-knee amputee who tries hard to manage a busy lifestyle. “We deal with a lot. And it’s hard not to take these issues to bed with us at night.”

“I feel like as amputees, we’re always dealing with one nagging issue or another,” says Hines. “It’s like the movie Groundhog Day, except I wake up each morning feeling tired and exhausted.”

WHY IS SLEEP SO IMPORTANT?

“Sleep is essential to every process in the body, affecting our physical and mental functioning the next day, our ability to fight disease and develop immunity, and our metabolism and chronic disease risk,” writes Erica Jansen, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. Sleep problems are linked to many chronic health conditions, including heart disease, kidney disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke, obesity, and depression.

Sleep deficiency is also linked to a higher chance of injury in adults, teens, and children. For example, drowsy driving (not related to alcohol) is responsible for a sizeable percentage of serious car-crash injuries and deaths. In older adults, sleep deficiency may be linked to a higher chance of falls and broken bones.

Feeling unrested and sluggish also can lead to lack of productivity and motivation, impairing our performance in school or on the job. It can negatively impact our feelings of self-worth and influence all our daily interactions. “Sleep disturbance is associated with major psychological and physiological stress and affects cognitive and functional abilities negatively,” notes Serda Em, lead author of a 2015 paper about amputee sleep habits. “Nontreated sleep disturbance leads to restricted social interaction and increased morbidity and mortality.”

It’s also important to recognize that sleep may be impacted by multiple comorbidities occurring at once. In a 2017 study published in the journal Nursing Outlook, the authors found that service members affected by extremity trauma experienced high levels of pain, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. They also found the greater the number of comorbid symptoms a patient had to deal with, the worse their overall health.

Those findings have obvious implications for amputees. We have a harder-than-usual experience in navigating the world, due to the obvious dexterity and mobility issues that are part of living with limb loss. We can feel clumsier. Sometimes we need more time to complete tasks. For many of us, limb loss was directly caused by another health challenge, such as diabetes, cancer, or trauma. And that’s to say nothing of the heavier cognitive load amputees carry just to get through every day.

“Time management itself can be so hard as an amputee,” says Hocker. “The mental game is kind of like a sport. It takes mental stamina, lots of thinking and preparation for everything. Even getting dressed in the morning can be arduous—picking out clothes, figuring out what shoes will work with my prosthesis, and planning for the details of each day can feel daunting. These things impact not only our jobs and ability to work, but they also impact our mood. They impact our daily interactions with family members and friends. All that overthinking and ruminating can make it hard to fall asleep.”

“Throw in the stress of dealing with fit issues, insurance hassles, and all the extra things rolling around in our heads,” Hines adds, “and it’s not surprising we have problems falling or staying asleep.”

DREAMING OF BETTER DATA

It takes determined effort to find any research about amputees’ sleep habits and the corresponding health effects. The most relevant study appeared in a 2015 issue of the Turkish Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. That paper, which examined the snooze life of 35 lower-limb amputees, concluded: “Our study has revealed that there is impairment in the sleep quality of the patients with [lower-limb amputation] compared with that of [control populations] . . . . Nontreated sleep disturbance leads to restricted social interaction and increased morbidity and mortality.”

The Turkish researchers found that older and more anxious patients had the most trouble sleeping, while urging that “further studies should be conducted with a larger population to reveal the causes of sleep disturbances and their effects on the general health condition.”

Unfortunately, that research hasn’t materialized, although a bit of tangential data has surfaced in research that’s focused on other aspects of limb loss. For example, a 2016 study by researchers from London South Bank University found that approximately half of phantom limb pain sufferers have disrupted sleep, with deleterious effects on their energy levels, mood, and decision-making. A 2018 article published in the Pakistan Journal of Physical Therapy found “a significant correlation between sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts with depression in lower-limb amputees.” And a 2021 paper in the Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness cited evidence that “individuals with disabilities have a higher prevalence of sleep disturbances when compared to their able-bodied counterparts.”

The scientific literature about amputees and sleep is thin enough that an undergraduate research paper offers one of the most complete snapshots on the subject. In 2019, Rachel Heatherly conducted a pilot study for her honors thesis project at East Carolina University. Titled “Chronic Pain, Sleep Disturbance, and Fatigue in Individuals With Lower-Limb Amputation,” Heatherly’s paper found “a positive correlation between neuropathic pain, sleep disturbance, and fatigue” among 25 people with limb loss. The study also noted that people who rely on prosthetic devices for mobility expend more energy and often incur compensatory musculoskeletal pain that can be chronic, with adverse effects on their sleep quality. “More research on symptom burden in the limb-loss individual is needed so we can better treat their pain and overall quality of life,” Heatherly argues.

“I do think that more research needs to be done with amputees specifically,” says DeChellis. “A lot of us have pretty significant real issues that impact our lives and ability to sleep well. When we get to talking with one another, we see that we have so much in common—depression, anxiety, pain, stress. These are very impactful on our lives, and our sleep.”

SNOOZE YOU CAN USE

While researchers have barely begun to ask questions about amputee sleep patterns, many people with limb difference have already figured out their own answers.

“I’ve tried lots of strategies to help get a good night sleep,” DeChellis says. “Some have worked, some haven’t.” After a lot of trial and error, she bought a high-end adjustable bed that can accommodate her orthopedic issues. “I’ve got Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a connective tissue disorder that has impacted my joints, including my cervical spine,” she explains. “I’ve found sleeping with one of those C-shaped airplane pillows really helps keep me more comfortable. I also take a warm shower at night, followed by applying a lavender lotion before I dim the lights with a good book and a cup of chamomile tea. Medication helps too.”

Hines wrestled with intractable phantom limb pain and back pain for many years. After trying various solutions, including targeted muscle reinnervation surgery, she talked with her medical team about trying a spinal cord stimulator. “So far it’s been working great,” she says. “I honestly wish I would have gotten it sooner. I spent way too many nights tossing and turning, and slogged through days on very little sleep. The stimulator seems to have done the trick.”

Hocker shares yet another strategy for getting better sleep. “My trainer has offered the fantastic advice to care for myself, starting at the cellular level,” she says. “For me, that means getting good exercise and hydration, making time for a hot bath, dimming the lights before bedtime, and ‘managing my moments.’ By this, I mean taking time out of my day to plan for all of my physical needs—including prosthetic—to be met ahead of time without feeling guilty about it. I need to make self-care a priority.”

Focusing on self-care doesn’t come easily to many in the limb-loss community. “I’m always asking myself, ‘How bad is it, really?’ compared to others who are not amputees,” DeChellis says. “There’s this sense that somehow if I just did something right, all of my issues would miraculously melt away, and that’s not the case.”

“As amputees, it’s like we’re always dealing with one nagging problem or another,” agrees Hines. “Pain, mobility issues, sometimes insurance hassles, and the stress that comes from dealing with so many things at the same time. Then we feel guilty and blame ourselves—I know I do. I think I should have all these things remedied by now.”

The reality for many amputees is that our challenges truly never go away. We’re left managing multiple issues related to our limb loss. We’re more than our limb loss, yet limb loss impacts so many areas of our lives. If we don’t begin to advocate for the things that improve our health, our well-being, and our quality of life, other aspects of our lives will suffer. Sleep quality is one subject that has tended to stay in the dark. It needs to be brought into the light.

Chris Prange-Morgan is an adoptive parent, patient advocate, trauma survivor, and hospital chaplain. She co-hosts the Full Catastrophe Parenting podcast with her husband, Scott.

Amputees and Sleep: The Rest of the Story

Here’s half a dozen tips to help you get better rest with limb loss.

AEROBIC EXERCISE

According to investigators at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 30 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise correlates with an increase in slow-wave sleep. This extremely deep form of slumber has restorative effects on body and brain. Exercise also helps stabilize mood and suppress anxiety.

BREATHING EXERCISES

The Sleep Foundation recommends various breathing exercises that, with practice, can slow the mind and relax the body. One method, belly breathing, shifts the focus from your lungs to your diaphragm. Two rhythmic methods (box breathing and 4-7-8 breathing) entail long, slow, deliberate cycles of inhalation and exhalation.

CBDs

Sleep researchers have found preliminary evidence that CBDs can lower anxiety, improve sleep scores, and relieve insomnia, REM sleep behavior disorder, and other syndromes. Hemp-derived CBD products are legal nationwide, and they do not contain enough THC to trigger a positive result on a drug test.

WEIGHTED BLANKETS

Experts claim the pressure from a weighted blanket increases production of serotinin, a brain chemical that promotes relaxation and peace of mind. Think of it as deep-pressure therapy in blanket form. In addition to promoting sleep, weighted blankets have proven effective in pain mitigation.

STRETCHING

A few minutes of stretching before bedtime can dissipate tension that’s piled up in your body during the day. It also loosens joints and soft tissues, while giving you a chance to focus on your own comfort and care. Combined with slow breathing, a leisurely stretching session can help you achieve a peaceful frame of mind.

DON’T SQUEEZE THE PILLOW

If you like to sleep with a pillow between your thighs, think twice. Experts at the Swedish prosthetics firm Lindhe Xtend note that this habit, over time, can change the shape and length of your muscles and cause other complications that impair your gait and lead to pain.