Back in 2015, when Katy Sullivan appeared in one of Amplitude‘s first print editions, she was shopping a comedy series that she billed as “an honest portrayal of someone living with a disability.” She’s still shopping that series, more evidence (as if any were needed) of the entertainment industry’s painfully slow embrace of inclusive storytelling. But now Sullivan has more firepower behind her project, thanks to her star turn in Cost of Living, the 2018 Pulitzer Prize winner in Drama. Her performance as Ani, a quadriplegic still recovering from the wounds of her failed marriage, brought a passel of award nominations as well as the attention of four-time Emmy winner Georgia Pritchett, a key figure in the creation of highly decorated shows like Veep and Succession. The two are working to bring Sullivan’s series to the screen at long last; they haven’t found a buyer yet, but there’s momentum.

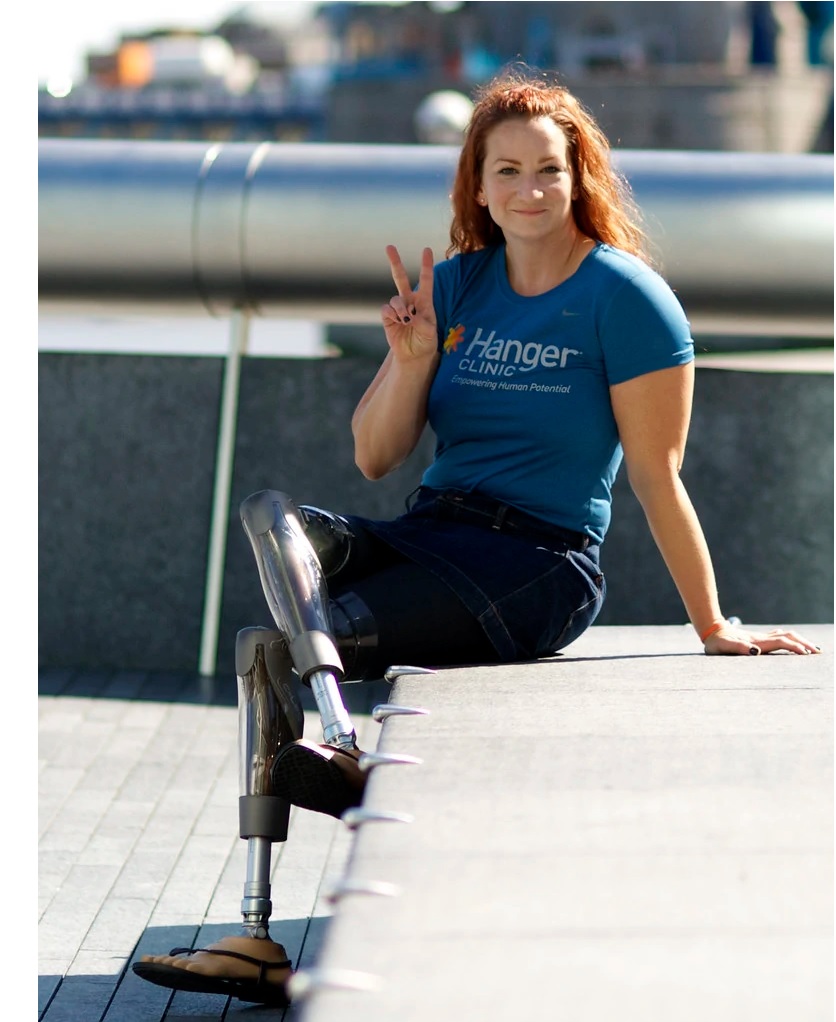

We spoke with Sullivan last month about her project’s status, her upcoming role in season 9 of Dexter (due out this fall on Showtime), and her unlikely and totally unexpected mid-career detour into international athletic competition, which culminated in a 6th-place finish at the 2012 Paralympic Games. Our conversation is edited for clarity. Images courtesy of Katy Sullivan.

Help me understand your journey from athletics to acting. Did that happen sequentially, or did they move on parallel tracks?

It’s actually the opposite of that. I’ve been acting my entire life, and athletics is this totally random thing in my life. I went to my first audition when I was 12, and I eventually got my degree in acting. I didn’t start running until I was in my 20s, when I had the opportunity to utilize some running blades, but I had never been an athlete before in my life. It turns out that I had some raw talent that we knew nothing about.

This was during a stretch where auditions and acting opportunities weren’t flying out at me all the time. So I looked at athletics as a chance to get a life skill, step way outside of my comfort zone, and do something I’ve never tried before. But I barely could call myself an athlete, and so I started looking at athletics from the perspective of an actor. I was like, what do I think an athlete would do? How would an athlete get motivated to wake up at four in the morning and go to the gym?

Like you were preparing for a role?

Yep. It honestly was sort of fake it till you make it. That’s how running happened in my life. I put running blades on for the first time in 2006, and I ended up competing at Nationals something like two months later, and it was insane. I was just so much out of my league. My first success in running was in 2007, when I did well enough at Nationals to get invited to go to the PanAm Games in Brazil with the US team.

After that I had my sights set on Beijing in 2008, but then I had a fall on the track and I hurt my back. That led to this careful-what-you-wish-for moment. Before my first track meet, I was so scared and nervous that I told my prosthetist I’d rather just sing the national anthem than run. So then I did get to sing the national anthem at Nationals two years later, because I was injured—and after I sang it, I sat in the stands with tears running down my face because I couldn’t run, and I knew I wasn’t going to make the Paralympic team.

About a year and half later, I had done a bunch of physical therapy and I was swimming and doing all these things, and London was close enough that I figured maybe it’s worth another shot. The fact that I am a Paralympic athlete is . . . . . bananas. If you had told me at 18 years old that I was going to go to the Paralympics, I would say you have me confused with someone else. That is not on my path.

Judging from your IMDb page, it looks like you started getting more acting work after the Paralympics in 2012. Is that a cause and effect?

I don’t know if I can say there’s a correlation, but I will say there has been a sort of tectonic shift in where people are being seen and how people are being seen. London was the first time he Paralympics were ever sold out. We also had more coverage across NBC’s networks than we had ever had before. I think people were starting to acknowledge challenged athletes, and that started to bleed into commercials, and the more we see people in commercials then that slowly leads into people being part of series and films and things like that. I think it’s just an overall shift in our society in recognizing that individuals with disabilities are 20 percent of the population.

So from a quantitative perspective, more people are getting more exposure to people with disabilities. Do you feel that increased awareness is also producing a qualitative shift, where people are deepening their understanding of who disabled people actually are?

I feel like we’re starting to see characters written more three-dimensionally. Traditionally, every role I got was either a tragedy or an inspiration. You were either sort of this hero figure or you had a tragic life, and there was very little in between. I think people are starting to understand that individuals with disabilities are three-dimensional people. We have problems. Some of us are jerks. Some of us are not inspiring, and we’re not always just a tragedy. There is this whole spectrum of complicated, flawed human beings with disabilities on the planet, and I’m starting to see more of that reflected in the work that I get as an actor.

The big shift for me happened when I got cast in a play called Cost of Living, which ended up winning the Pulitzer Prize in 2018. That character is not necessarily the most likable person on the planet. But it’s an honest character. She’s been hurt. She’s overcoming this disability that’s been sort of thrust upon her in her life, and she’s trying to manage her relationship with her ex-husband, and it’s a complicated story. It’s not just about disability. There are no teachable moments in that play. My character never mentions anything about her disability, and we didn’t feel it was our job to be an encyclopedia of disability. It’s all about telling a compelling story. Are you drawing people into the story to the point that people forget your character is sitting in a wheelchair or using a prosthetic limb? If the storytelling is good enough, it’s not going to matter.

Tell me about the genesis of that role. How did you get the opportunity to create that character and then take the show to New York?

I was actually out in LA at the time, and I was asked to audition. I read the play and felt two things at once. One, I was really terrified of it because of how vulnerable this character is and how how deep she goes. I felt, “Oh gosh. This is terrifying—but that’s probably a sign I should do it.”

The other thing was that I was curious about Martyna Majok, the playwright. I thought she had to be someone who needs to be taken care of or has been a caregiver, because the play is just way too accurate about those relationships. And it actually turns out that she was a caregiver for a spell, to a young man who had cerebral palsy. The character of John in the play is based on that experience.

So I auditioned. I sent in a tape because they were auditioning in New York. Then the director came out to LA to do another play, and she asked if I would come in for a callback. Then I ended up doing a workshop of the play, which was a week in New York. And then from there we went to Williamstown, and you know the rest. There’s nothing quite like getting to originate a role and take her from the page to the stage. And then to be able to go all the way off-Broadway, and the fact that it’s continuing to have a life, is amazing.

I already asked you whether being in the Paralympics gave your acting career a shot in the arm. What has been the effect of being in a Pulitzer Prize-winning play?

Cost of Living was a was a game-changer in my life and my career. When you can put Pulitzer Prize and your name and the same sentence, it’s pretty extraordinary.

Do you think getting the role in Dexter was a direct result of that?

I don’t know if that has anything to do with it. You still have to go through auditions and callbacks, and this happened to be a series of Zoom callbacks, which is its own challenge. But for sure there’s a cumulative effect of putting together a body of work and people starting to say, “Okay. Well, this woman actually knows what she’s doing.”

So who is your character in Dexter? What made her attractive for you?

I can’t share too much because I’ve signed NDAs up the wazoo. But one of the things that I appreciate so much is that her disability kind of has nothing to do with anything that happens to her. She’s just going about her life, doing her job—she’s the police dispatcher in this small town where the season takes place—and it’s never discussed. She’s just a human being who happens to live her life this way, which is what I’ve been hoping and praying for my whole career.

If you look at any marginalized group in Hollywood, there comes a point where they will say: Can we tell our own stories? Like, can’t we? I think we’re starting to see a small emergence of people [with disabilities] who are developing their own projects. I’m currently in the process of trying pitch a television show that is trying to do just that. It’s about a woman with limb loss, and she’s not extraordinary. She’s just trying to put one foot in front of the other, and she’s a bit of a train wreck. She’s not superhuman, and she has a truckload of flaws, and I feel like these are the stories that we we’re starting to see more and more. We’ve gotten a lot of “nos” because I think it’s a scary place for people to want to go; there’s still this feeling that the [disabled] character has to be elevated in some way. But I’m dying to do Sex and the City with a disabled Terry Bradshaw, because that is our experience. We don’t know anything different. I’m living my life and dating and being in relationships and having friends, all with a disability, and it’s totally normal.

If you’ve already gotten some “nos,” it sounds like you’re pretty far along in developing this idea. Where do things stand? Like, have you shot a pilot yet?

We have a pilot written, and we’re taking it out to networks and platforms. We partnered with a writer named Georgia Pritchett, who is from Veep and Succession, and now she’s doing a limited series for Apple called The Shrink Next Door. Our show is called Legs, and it’s a series about a woman who lives her life on two prosthetic legs, but she kind of feels like that’s the least of her problems.

We’ve had some really great meetings. I’m not sure if the show will get picked up or if it will get produced. But the more people that show up in these offices and say “This needs to be seen,” the closer we’ll get to the tipping point. It’s exciting to be a part of that process.