Limb-different protagonists are increasingly common in popular fiction—and the books are flying off the shelves.

by Julia Layton

J.K. Rowling introduced a new protagonist in 2013, and he was a rare breed. Cormoran Strike, who carries the eponymous detective series, is a lot of things: a crime-solving private investigator, a war vet, and a man running from his family name. He’s also an amputee.

You don’t find a lot of multifaceted limb-different protagonists in popular fiction, let alone driving a story that’s not about limb difference. Amputees are often stock characters or plot devices, defined by their missing limbs.

“Some literary portrayals no doubt reinforce stereotypes,” says Erik Grayson, associate professor of English at Northampton Community College and co-editor of the essay collection Amputation in Literature and Film. “For instance, horror films often feature amputees as either a terrifying Other or as a victim. Somewhat similarly, some urban legends, such as ‘The Hook Man,’ deploy images of amputees with weaponized prostheses as the antagonist. In war literature and cinema, on the other hand, amputees often serve to emphasize the physical toll of state violence and enlist audience sympathy.”

Increasingly, however, authors are going another way with it. Rowling is just one of a growing number of fiction writers who are normalizing limb difference by creating complex, relatable amputee protagonists. Far from one-dimensional symbols, these characters struggle with limb loss the way others struggle with PTSD or a bad heart: as an obstacle they have to overcome to live their lives. And readers seem to be buying it.

The Literary Draw

As far as character traits go, “difference” can be a gold mine. It allows novelists to dig deep into an individual’s psychology—their grieving process, coping mechanisms, resilience, perceptions of Self and Other, and countless other rabbit holes of character development.

For Mark de Castrique, author of the Blackman Agency Investigations series, limb difference provides a critical component of protagonist Sam Blackman. The first book in the series, Blackman’s Coffin, features a plot that stretches back to the Jim Crow-era South. Blackman serves as the link between a 1918 murder in Asheville, North Carolina, and the present-day murder of his friend.

“I needed a character with investigative experience,” de Castrique says, as well as “an outsider who would learn about Asheville and its history along with the reader.” He also needed his protagonist to have an internal conflict that would engage audiences and simultaneously evoke the social fault lines that divide Southern communities like Asheville. It was 2007, and he found it at the local VA hospital, where there was a steady stream of soldiers returning maimed from the war in Iraq.

“I thought if my character were in the VA hospital with an injury that had required amputation of part of his leg, he would be dealing with both physical and psychological challenges,” says de Castrique. “How much of his identity is tied to his physical status? [How will he adjust to] loss, prosthetic devices, and physical therapy?”

Limb loss begins the action, and it’s there all the way through Blackman’s Coffin: Upon leaving the hospital, Sam finds out an amputee he’d befriended there was murdered. “As he struggles to deal with his physical adjustments, he throws himself into solving the murder of his fellow amputee,” de Castrique says. “The search for answers runs parallel to Sam’s search for ‘wholeness’ as he deals with his recovery.”

Mainstream Perceptions

Yet for all its exploratory potential, limb difference can pose challenges in creating a protagonist, both in realism and relatability. Normalizing limb difference for a general audience is no small thing.

Roughly 2 million people in the United States live with limb loss, and many of them face the effects of stigmatization every day. A 2017 study in the Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics revealed amputees commonly experience negative interpersonal interactions after limb loss, even with loved ones, along with being avoided, stared at, and asked intimate questions when in public.

Even in a cultural moment laser-focused on inclusion, limb-different people hover at the margins of social visibility. Maren Scheurer, professor of comparative literature at Germany’s Goethe University (and Grayson’s co-editor), believes it may have something to do with “ideals of bodily integrity and independence, a reminder that our bodies simply are not invulnerable and completely controllable.”

According to Grayson, literary visibility can make a difference. “Literature, in the right hands, can illuminate those corners of society of which the reading public might otherwise be unaware,” he says. He points to Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Jungle, which changed the course of history, but notes that many other books have inspired personal change on a smaller scale.

“Of course,” Grayson adds, “representation matters at least as much as visibility does”—and representing limb difference can be tricky. Like any non-normative trait, it resists general understanding. For writers who haven’t actually experienced limb difference, inauthenticity is a huge concern.

“The greatest risk I felt was that I wasn’t an amputee, yet I’m trying to speak for a character who is,” notes de Castrique. “I don’t know what it’s like, but I wanted it to ring true.”

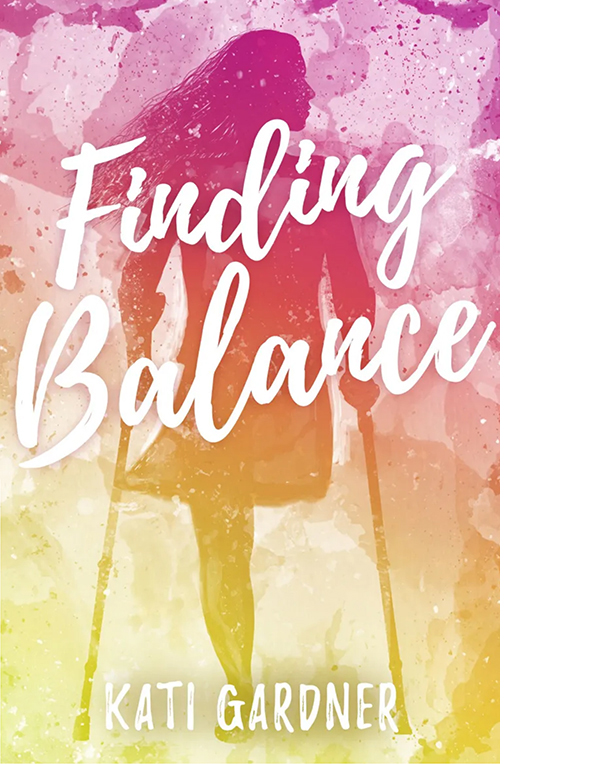

Unfortunately, limb-different characters often ring hollow—at least to limb-different readers. For writer and lower-limb amputee Kati Gardner, author of the young-adult novels Brave Enough and Finding Balance, writing amputee protagonists allows her to clarify things. For instance, Mari—the protagonist in Finding Balance—falls down a lot, partly because, Gardner says, “I feel like people forget that we do that.”

Mari lost her leg to cancer. The teen is trying to put the illness behind her—other cancer survivors can do that—but her missing limb constantly reminds everyone of her past. Gardner wanted readers to know what it was really like to be Mari.

“I felt like when I would read other books with characters that had amputations, they never could quite get it right—that something would be left out,” Gardner says. “I knew that I could write an authentic amputee without leaning into tropes or stereotypes.” It’s not an easy thing, she admits. “I think you have to really buy into it. You can’t forget at any point that your character is an amputee. Every move they make, if they’re a lower-limb amputee, is impacted by their amputation.”

You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know

The learning curve for difference can be steep. Julia Heaberlin learned as much while writing her crime novel We Are All the Same in the Dark.

In Heaberlin’s typical process, she sees a character first. She starts writing the character, and stuff starts happening—the character reveals the plot. In this case, the author says, “There was this girl haunting me. She was standing in a field of dandelions making wishes, and I knew not much about her except that I knew she only had one eye. And so I started writing, except nothing was happening. And so I thought, ‘This is a complete cliche. I have no idea what I’m talking about.’”

As luck would have it, a world-famous ocularist lived 30 minutes from Heaberlin’s house, and he invited her into his world. Eventually, he introduced her to some of his clients, and the succession of interviews that followed helped shape the novel’s two protagonists: Odette Tucker, a young female cop with a dark past and a missing leg, and Angel, the lost one-eyed girl Odette is intent on saving.

Heaberlin’s research shattered her perceptions of beauty, physical difference, and disability. An Instagram model told Heaberlin she has a secret: a prosthetic eye, which even some of her closest friends don’t know about. A 16-year-old girl who’d lost an eye told the author, “You know what? It’s just not that hard.” And Lauren Scruggs Kennedy, who lost an eye and an arm when she walked into the spinning blade of a propeller plane, questioned the application of terms like “disabled” and “differently abled.”

“Because, you know, if you’re going to apply the label to one person,” Heaberlin explains, “you should apply it to everyone, because we are all disabled in some way.”

By the time Heaberlin spoke with a below-knee amputee to help her get inside the mind of Odette, her ideas about capability and disability had been turned upside down. Her source, a SWAT trainer and ex-cop, “was kind enough to let me ask every little question that I wanted,” she recalls, “including, like, how do you go to the bathroom in the middle of the night, things like that.” She tried to pay attention to detail, the little day-to-day things that bring a character to life. During a visit to the prosthetics lab at the University of Texas, she learned in passing that limb-different people tend to be concerned with their healthy limbs.

“One guy working there said he’d almost got in a fight the night before,” recalls Heaberlin, “and he just casually mentioned, ‘I’m not worried about my prosthesis. I’m worried about my good leg. So I always protect that.’ [It’s] those tiny little details that if you screw them up, the people who know [will realize] you don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Toward Normalization

There are certainly aspects of limb difference that aren’t broadly relatable, admits de Castrique. Some knowledge doesn’t transfer. “I don’t know what it’s like to look down and see nothing where my leg or arm should be,” he says. “I don’t know what it’s like to endure phantom limb pain, or to feel people might be pitying me. And even as I say this, the very fact that they’re unrelatable means I must know I’m probably getting it wrong.”

Still, de Castrique thinks everyone can understand limb difference to some extent, because we’ve all faced challenges at some point. “I think anyone who has gone through some major life-changing event—illness, accident, or some other upending occurrence—can feel sympathy and even empathy for limb loss,” he says. “People connect with Sam [Blackman]. They have sympathy for him, but not pity. That was very important for both Sam and me. And I get emails from readers who appreciate the way Sam represents wounded vets and amputees without becoming maudlin.”

In a culture that generally doesn’t want to look at difference or disability, accurate and truthful amputee characters can give people with limb difference “a sense of being ‘seen,’” says Grayson. As literary visibility increases, he suggests, it may cause more body-normative people to question their assumptions about limb loss.

Visibility took on literal meaning for Kati Gardner with Finding Balance. She wanted an actual image of limb difference on the front of the book. She fought for it and won.

“I just desperately wanted a one-legged girl on the cover,” she says. “I had never seen a YA book with a one-legged character on the front, and I just thought it would be really impactful.”

The illustration is serene. A girl with soft edges stands with her back to us, in shadow, her left leg framed by crutches, revealing her profile as she looks at something off the page. It could very well have impact: Numerous studies have found non-disabled subjects have more positive perceptions of people with disabilities after viewing positive representations of them.

Readers, for their part, seem to have no trouble connecting with limb-different protagonists. Sam Blackman, whom de Castrique initially conceived for a single book, now carries a series numbered at eight novels and counting. Heaberlin’s We Are All the Same in the Dark has been optioned for a television series. And Rowling’s Cormoran Strike has been solving crimes on the page since 2013 and on the BBC since 2017.

The trend is good for everyone, not just amputees, notes Scheurer. She thinks normalization of limb difference has universal benefit. “Since we are all embodied beings, the representation of disabled people is not just a matter of social justice, although that is a very important aspect of it,” she writes via email. “But since we all have bodies with vastly different shapes and dis/abilities, greater visibility of physical differences ultimately concerns us all.”

More Amplitude articles about amputee books

“Nature’s the Best Medicine for Limb Loss,” December 8, 2021

“Fun Summer Reads for Amputees,” July 21, 2021

“Christa Couture’s Extraordinary Book About Limb Loss,” May 19, 2021

“Books About Amputees and Limb Loss You Might Have Missed,” December 2, 2020

“5 Reasons Why Amputees Make Better Spies,” March 12, 2020