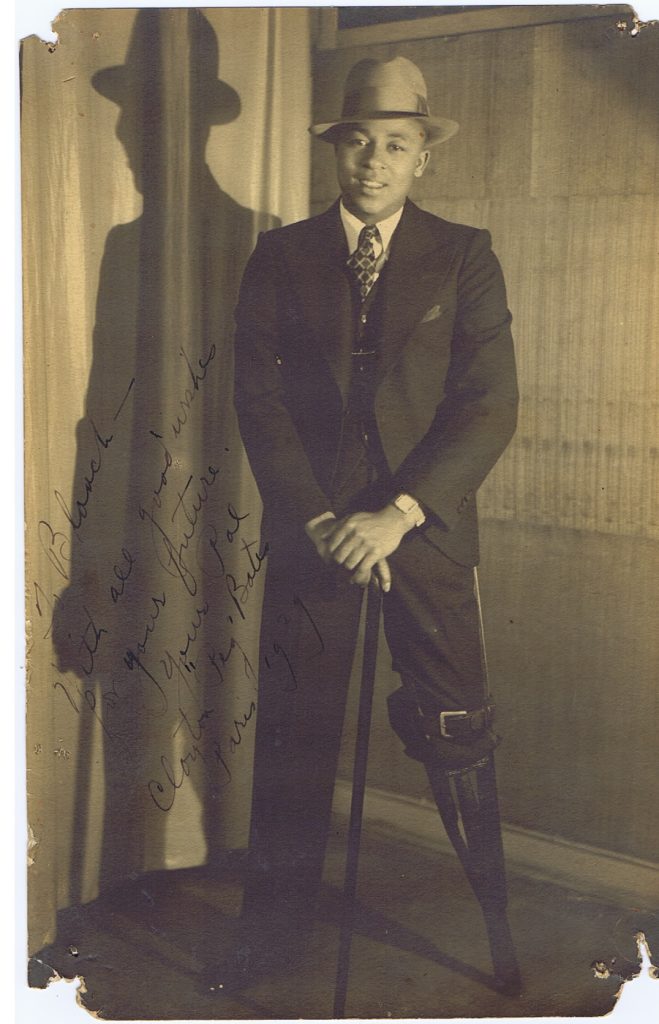

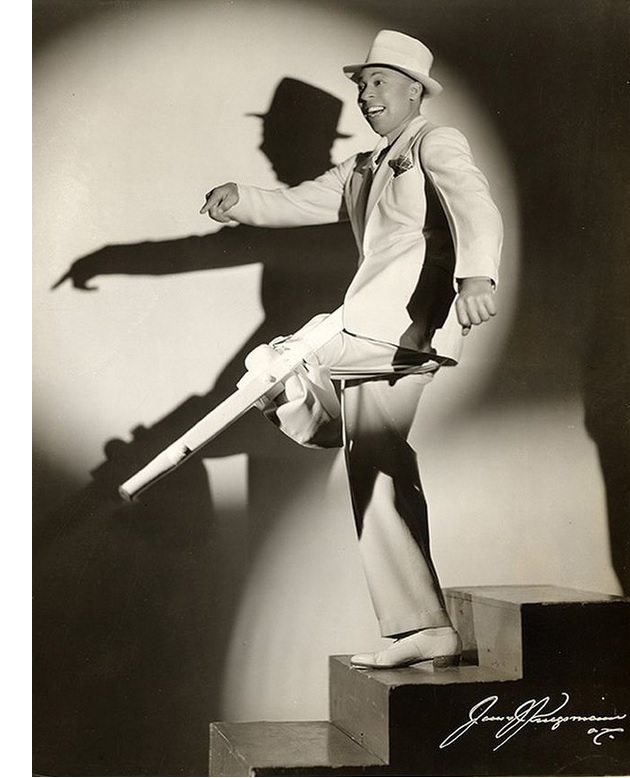

Serious dance aficionados don’t need to be told who Clayton “Peg-Leg” Bates is. But we would never have heard of him if not for loyal Amplitude reader Lauren Pine, who tipped us off via a couple of Instagram posts. Why has Hollywood not made a biopic of this man yet? A below-knee amputee from the age of 12, Bates grew up disabled and Black in the Jim Crow South, latched onto the vaudeville circuit as a teenager in the 1920s, and eventually took his place alongside the greatest hoofers in the Golden Age of Dance. Equally revered by audiences and fellow entertainers, he shared the stage with icons such as Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Fred Astaire, and Gene Kelly. Half a century later, Bates was still kicking it with performers of Gregory Hines’ generation. The International Tap Dance Hall of Fame (where he was among the earliest inductees) called Bates “one of the finest rhythm dancers in the history of tap dancing”—abled or disabled.

This short video clip from the 1930s, the oldest one we could find, gives you a glimpse of Peg-Leg at the height of his powers.

“He was reaching for things and trying things and pushing himself,” said Gregory Hines in The Dancing Man, a 1991 PBS documentary about Bates. “He was accomplishing things so he would be respected on the same level of somebody like Bunny Briggs or Teddy Hale. And he was. Tap dancers were trying to do the rhythms that Peg Leg was doing. He would use that peg in a way that drummers were doing, and [other dancers] were trying to hear it and make it work with their feet. He was expressing himself in a way that other tap dancers couldn’t.”

Here’s the New Yorker describing a Bates performance at a USO show during World War II: “We saw Peg-Leg when he was finishing an engagement at the Capitol [Theatre] the other day and preparing to go on tour. One of the things he had been doing five times daily was imitate a dive bomber. He’d do this by jumping five and a half feet into the air, turning completely around, and making a one-point landing on his peg leg. Then, still on the peg, he’d back into the wings while flapping his arms.”

Born just outside Greenville, South Carolina, in 1907, Bates lost his leg in an accident at the cotton-seed mill where he worked as a kid. An uncle carved him a wooden prosthesis, and that’s what Bates learned to dance on. More than a mere novelty, the peg leg enhanced the quality of Bates’s dancing by giving him a unique bass tone to pair with the metallic snap of his taps. It also gave him a good-sized chip on his shoulder, steeling his resolve to be taken seriously as a dancer rather than dismissed as a curiosity.

“I didn’t want nobody’s sympathy,” Bates said in The Dancing Man. “I wanted to dance on this peg, and I wanted to do some steps on this peg that even two-legged dancers can’t do. And I didn’t let anything stop me.”

Bates got his big break when he was spotted by Broadway producer Lew Leslie and added to the lineup of Blackbirds of 1928. That landmark show, one of the first Broadway smashes to feature an all-Black cast, launched Bates into the industry’s top rank. He became a fixture in New York’s theaters and nightclubs, toured Europe and Australia, danced at Radio City Music Hall (the second Black performer to do so), and appeared with big-band legends such as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Jimmy Dorsey, and Cab Calloway.

During World War II he developed a special rapport with wounded veterans. Bates devoted the bulk of his time to the war effort during the 1940s, performing both for active-duty soldiers and injured vets. His limb difference gave him a natural connection with injured men, whom he routinely greeted in person on the hospital wards as a de facto peer mentor. “I just talk everyday logic,” he told the New Yorker. “I tell them [disability] can happen to anyone, and there’s no such thing as a handicap.” When hospital audiences erupted in applause during his shows, he used to joke: “All you got to do is encourage me, and I’ll break the other leg!”

Bates eventually became a fixture on the Ed Sullivan Show and performed twice for Queen Elizabeth. And in 1951, as the civil rights movement was gathering steam, he struck his own small blow for integration by opening the first Black-owned resort in the Catskills—one of only about a dozen Black-owned performance venues in the whole country at that time. For someone who started his career performing in venues that rejected Black patrons, it was a profound act of independence. He owned and operated the club for 30-plus years.

Earlier this year, Hudson West Productions released a 30th anniversary edition of The Dancing Man. The last time we attempted to log in, we got an error message, but we’re providing the link anyway in the hope that it’s a temporary server error. In lieu of that, here are a few other short video clips that we fetched from YouTube:

Ed Sullivan Appearance, early 1950s

Ed Sullivan Appearance, mid 1960s

With Charles Cook and Earnest Brown, c. 1980s