Advertisers have started to discover the powerful impact of disability-related content. Toyota’s Super Bowl ad featuring amputee swimmer Jessica Long won numerous awards a couple of years ago, and Apple’s 2022 spot “The Greatest” scored multiple best-of awards. Target, Jeep, Nike, and Microsoft are among the other high-profile brands that have recently featured amputees and other people with disabilities in their marketing campaigns.

But while people with disabilities are gaining visibility as the subjects of advertising, they’re still nearly invisible within the agencies that create ad campaigns. That’s a problem industry veteran Hugh Boyle intends to correct with the launch of Doable, the nation’s first advertising firm to feature the talent of writers, artists, photographers, and other creatives who have disabilities.

“If there are no disabled people in art rooms or copy rooms, then the way disability is represented in advertising is inevitably going to be bad,” says Boyle, who has held senior positions with major agencies in both the United States and the UK. “I’m in this unique situation of being in this industry for 30 years, and suddenly seeing the world through a very different pair of eyes.”

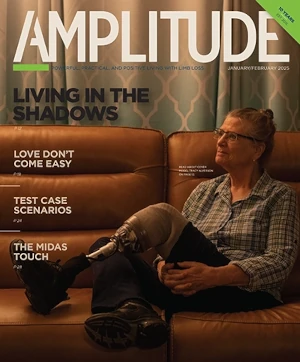

His outlook changed last year when he lost his right leg below the knee. The limb had been “wonky” (Boyle’s term) for nearly a decade before that, subjected to multiple surgeries to stabilize the ankle joint. Worsening pain and chronic infection finally made the leg more trouble than it was worth. Boyle chose amputation in order to reclaim his quality of life. But he worried that the loss of a limb would force him out of a profession in which he excelled for decades as an able-bodied person—and that seemed manifestly unfair.

Fast forward 15 months, and Boyle and his partner, fellow industry veteran Bob Wagner (who’s hearing impaired), are building a new niche to serve disabled consumers and creative pros alike. We talked recently with Boyle to learn more about the origins of Doable and its companion entity, the Consumers With Disabilities Research Foundation (CoDi). The firm is actively looking for talent, as well as consumers to participate in market research. If you’re interested in getting involved, here’s the front door.

Our conversation is edited for length and clarity.

How did the idea for Doable come to you?

It happened as I was lying in a hospital bed. I looked down at the place where my leg used to be—that hits you hard—and my initial reaction was, “What the hell am I gonna do?” I’ve only ever worked in an industry that has to be described as a high-touch industry. Lots of travel, lots of meetings, lots of expos. I knew, regardless of how solid of a recovery I made, that I simply wouldn’t be able to operate the way I had been for decades before.

My next thought was to ask myself, “I’ve worked in this industry for 30 years at two of the biggest companies in the industry on both sides of the Atlantic. How many people with any form of disabilities, specifically a physical disability, have I ever worked with?” Unbelievably, the answer to that question was one. Just one guy, in London, who had spinal issues when he was a kid, He had one leg considerably shorter than the other, so he walked with a very pronounced and awkward gait. He was very talented, but perhaps he didn’t rise as high in the industry as an able-bodied person would have.

Do you think you recognized this bias before you became disabled yourself?

Yes, it’s kind of a big flashing neon sign. You can’t avoid it. Advertising is a beautiful-people industry. You don’t see many people who don’t fit the norm in an industry such as that.

So my next thought, and it was a preposterous thought, was: Well, maybe the talent isn’t there [within the disability community]. But within half an hour of research, I could see what a ridiculous thing that was to say. The talent is there in abundance. The disabled community is rich and vibrant in its creative capabilities. There are actually two societies of disabled professional photographers in North America. There’s a group of professional disabled videographers. There’s an enormous group of disabled copywriters. All of these people were ganging together and saying, “Look at us; we’re here.” But in my experience, these people were basically invisible within the industry.

When I started to reach out to these people, the seminal moment for me was speaking to a copywriter who has been blind since birth. As I talked to him, and as I read his work, I thought to myself: “What agency wouldn’t want to work with this copywriter, when words have been the primary means this person has had to decode the world?” Words are the currency with which he has made sense of the world. My God, that’s the perfect set of ingredients for a great writer.

At what point did you start thinking about bringing all of this talent together into an actual agency?

The situation just started to lay itself out in front of me. During the three or four months before the amputation, when I knew I was losing my leg, I was asking myself: “Why is this happening to me?” Suddenly I started to think, “This is why it’s happening.” I’m in this unique situation of being in this industry for 30 years, and suddenly seeing the world through a very different pair of eyes. I understand the industry, I understand the need, and I know how to fix it. And I never, ever wanted to do something as much as I want to do this.

There’s one other piece of serendipity you should know about. As I’m thinking about this, I realized that if we’re going to do this with credibility, if we’re going to staff a creative agency with people who have disabilities, we also need a research agency providing the data and insights to support great work. But there’s no market research organization in America that’s dedicated to speaking with disabled people about why they buy what they buy and why they like what they like. This, despite the fact that the disabled population has disposable income of $480 billion. There is, however, a nonprofit in the United Kingdom that has been doing this sort of market research for 30 years. It’s called the Research Institute for Disabled Consumers. So as I’m flicking through their website, I click on the page that says trustees, and it turns out that the only guy with a disability who I ever worked with in the advertising industry—the guy with the congenital spinal injury—is a trustee of this nonprofit. I saw that and I thought, “This is meant to happen.”

So in addition to Doable, you’re also launching a research institute, correct?

That’s right. We’re calling our research business the Consumers With Disabilities Research Foundation. We’re going to put together a panel of 3,000 to 5,000 consumers who will be generously remunerated for their participation in research. It will be independent of the creative services agency, because I don’t want there to be any suggestion that you can only use the only use the research company if you use Doable to do your creative work. That would just be nonsense. So any agency or organization can use the research company. And a couple of times a year we’re going to run a piece of proprietary research of our own design.

How did you get connected with Bob Wagner?

I met Bob through an ex-colleague of mine. She’s had breast cancer and had a double mastectomy, and she knew a lot about the ADA because it supports people who have, or are recovering from, long-term sickness, because the outcomes of that are not dissimilar to those who have lifelong disabilities, right? So I had lunch with her, and she said, “You’ve got to meet a guy named Bob Wagner. He has been in agencies for 30 years. He’s congenitally deaf and has been since he was a child, and he’s managed to survive the industry by lying about his deafness for decades. He used to grow his hair long to conceal his hearing aids. He used to wear eyeglasses, even though he doesn’t need them, to conceal his hearing aids. Because he knew that opening up about his deafness would be deleterious to his career progression chances.

So we’re an interesting pair in that Bob has been disabled all of his life and sees the world that way, and I’ve been through the travails of the industry as a perfectly able-bodied guy until 18 months ago. So we cover both sides—those born with a disability, and those who become disabled later in life.

There’s been so much growth in the adaptive clothing industry, and those brands are big advertisers. I’m curious if you’ve made any connections within that niche?

So I met a filmmaker, an amputee, who is used by Tommy Hilfiger to make their adaptive clothing commercials. And his work is brilliant. It’s as good if not better than every other piece of work they do for every other product line. So your first reaction is, “Good for them for using an adaptive filmmaker to create the spots for their adaptive line.” But they’ll never use him on anything else. I think that’s a fascinating thing. They score the points for having him do the work. But they could make themselves heroes if they then used this guy to do work for their non-adaptive lines.

I would love it if one day, a team of disabled creatives pitched a client without the client knowing they were disabled, and they won the business on purely on the merits. I would love it if, in five years time, people who have worked at Doable are working at Ogilvy and other big-name agencies. That would be a real success.