By Eric Gabriel, EdD

A person’s identity plays a vital role in his or her life.

I am a 62-year-old bilateral amputee who, after 63 orthopedic operations, has relied on my athletic identity to push me to achievement through years of medical change and physical and emotional hardship. Before having my right leg amputated ten years ago, I was a competitive softball player. After my amputation, I was fitted for my first prosthesis and took up competitive adaptive rowing. When I also had to have my left leg amputated in 2018, my athletic identity again set the tone for my goal setting, self-determination, and motivation to overcome the challenges.

As a bilateral above-knee amputee, I had a new challenge to face—not being able to walk. To overcome this obstacle, at first I used a wheelchair and believed that I would probably need it for the rest of my life. It wasn’t my first choice for remaining mobile, but I saw no other feasible options. I was willing to do whatever I needed to do to be able to get around and live my life.

It’s important for our chances for a full life to be willing to try things that we might at first consider rejecting. A prosthetic hook. A wheelchair. Crutches, a cane, or a walker. Or something else. Our rejection of these devices out of hand might be costly. Those who are unwilling to try a hook may lose the many abilities that such a tool could make possible. People who refuse to use crutches, canes, walkers, or wheelchairs may be injured if they fall or they may lose their mobility altogether. On the other hand, by giving these devices a try, we might stumble on the right solution for our situation.

While regularly using a wheelchair, I began to consider a type of prostheses known variously as foreshortened prostheses, platforms, or stubbies. These are prosthetic legs for bilateral above-knee amputees that are more like short stilts without knees with a variety of possible foot designs, ranging from standard prosthetic feet to rocker bottom platforms. Because they are so short and have no knee joints, they are easier to walk in, easier to maintain balance in, require less energy expenditure than full-length prostheses, and reduce the risk of falling. There is also less risk of serious injury if a fall does occur. But more importantly for me, they would be providing my first steps out of my wheelchair, moving toward building myself up to getting knee-jointed prostheses that offer more freedom of movement and give me my identity back as a 6-foot-5-inch-tall man.

Dave Sickles, ACM, CPO, CPed, and the prosthetic team at Hanger Clinic offered to help get me back on my “feet,” and I decided to go for it.

At first, I was so grateful about the possibility of getting out of my wheelchair, and these folks were offering me the vehicle to do so. They described how the stubbies looked and how they would function. I was skeptical, however, about my reduced height when wearing these devices. While I was sitting in my wheelchair, my height was disguised. I still had the upper-body height of a 6-foot-5 male. Thinking about losing that identity was hurting my ego in a way that no medicine could help. Still, the pros seemed to outweigh the cons, and I was elated at the thought of getting out of my wheelchair and gaining more freedom and independence.

When Dave brought the stubbies to my house for the first fitting and stood them up in my living room, however, tears came to my eyes. As ungrateful as this sounds, they were not the tears of joy I had anticipated. They were tears from the shock of reality. My thoughts of standing and gaining independence were overcome by the realization of how short and awkward looking the stubbies were and how short and awkward looking I would be. The stubbies looked to me as if they were as wide as they were long. They were just two sockets that would cover my residual limbs with very small paddles on the bottom that would act as feet. Wearing these would make me shorter than if I sat up in my wheelchair. What should have been tears of joy and thanks became tears of embarrassment. At that point, I felt safer, emotionally, staying in a wheelchair for the rest of my life.

I knew that I could function just fine in a wheelchair. Why should I put myself through countless rehab hours with more frustration than triumph? Why not give up? I’ve paid my dues in the rehab world.

That’s when I had to step away, take a deep breath, and consider the positives, not the negatives.

My ego was in the way, which made me see only the height issue and the fear of what people might say and think when they see me waddle by instead of realizing that this was a gift. But after the initial shock wore off, I realized that using the stubbies might literally be the first step at working toward mobility and getting bigger and more functional prostheses in the future—the first step toward regaining my identity. Training and working out with weights throughout my life taught me that you have to break down the muscle to build it back up. This was my break down time.

When I showed up at the clinic in my wheelchair. I hadn’t stood up in more than nine months and had to learn to walk in my stubbies.

The stubbies, which give me a standing height of only 4 feet 5 inches, are to help me get my strength and balance back, and when I gain that back, I can potentially start wearing taller prosthetic legs. My final goal is to use full-length prostheses with computerized knees and to regain my original height, which is one of the cornerstones of my identity.

When it came time to try the stubbies for the first time, I sat at one end of the parallel bars with a full-length mirror at the other end. It was soul-searching time filled with nervousness and apprehension. Could I go on this rehabilitation journey? If not, would I be content with remaining in a wheelchair for the rest of my life?

The mirror at the other end of the parallel bars seemed miles and years away.

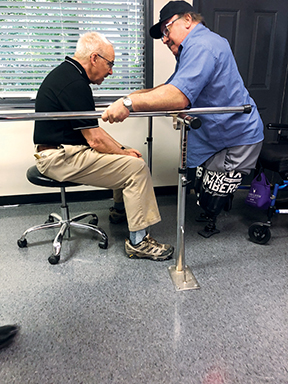

The morning consisted of three fittings/modifications, and each was as difficult and uncomfortable as the previous one, mostly because of my own physical makeup. Next came the hard part—standing up for the first time in a long time. With the help of others and the use of my upper-body strength to push me up using the parallel bars, I was finally standing. On the third try, I took three baby steps, probably going only two feet. But to me, it was like competing in a marathon. The mirror still seemed like it was a couple of miles away, but by slowly tapping into my athletic identity, I knew I would reach it.

My initial goal is to wear my stubbies only around the house. It will be a slow learning process. First, I must be able to put both stubbies on and stand on my own. My second milestone will be learning to get out of my wheelchair and walk to the couch or another close piece of furniture. This will involve using nearby furniture, walls, and a walker for support. My third milestone will be building up my strength and balance to walk from room to room in my house, eventually without the use of the walker or any other assistance. With my strength, balance, and confidence built up, my fourth milestone will be to have my wife take me to a public place and walk in front of strangers. I need to conquer the stares and awkward questions that may be asked. These milestones are important for me because I know that the achievement of each one leads me closer to the next set of prostheses and standing taller and taller.

My intention is to work on my milestones every day. My stubbies now represent a symbol of hope. There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t visualize using them, training with them, gaining strength and balance with them, and finally regaining my identity and independence.

I now look at a negative perception by others as challenge. While there will be some tough days ahead, I will take a deep breath, pick myself back up, and proceed one step, one milestone, at a time. I am so thankful to have this opportunity when so many others don’t.

I go to rehab once a week and walk between the parallel bars, with progress happening each session. When at home, I practice standing and stretching. Getting my strength and balance back is key.

Last April, I was determined to ride my wheelchair across the stage to accept my doctoral degree—and I did so. This March, I am equally determined to wear my stubbies at the United States adaptive rowing championship in Boston. I intend to keep moving forward and stand up as a champion.

My need to regain my identity may actually be the instrumental goal that helps me get out of my wheelchair and walk independently again. Maybe I won’t get back to my original height, but I will be functional and independent. And that’s nothing to be ashamed of.

Regardless of my height, I will be standing tall.