Limb loss made global headlines last week after the journal Nature published evidence of a successful medical amputation that took place 31,000 years ago in present-day Borneo. The new discovery isn’t merely the oldest known case of limb removal. It’s the earliest documented surgery of any kind, by many thousands of years. Ergo it radically rewrites the timeline of how human medical knowledge and practice evolved.

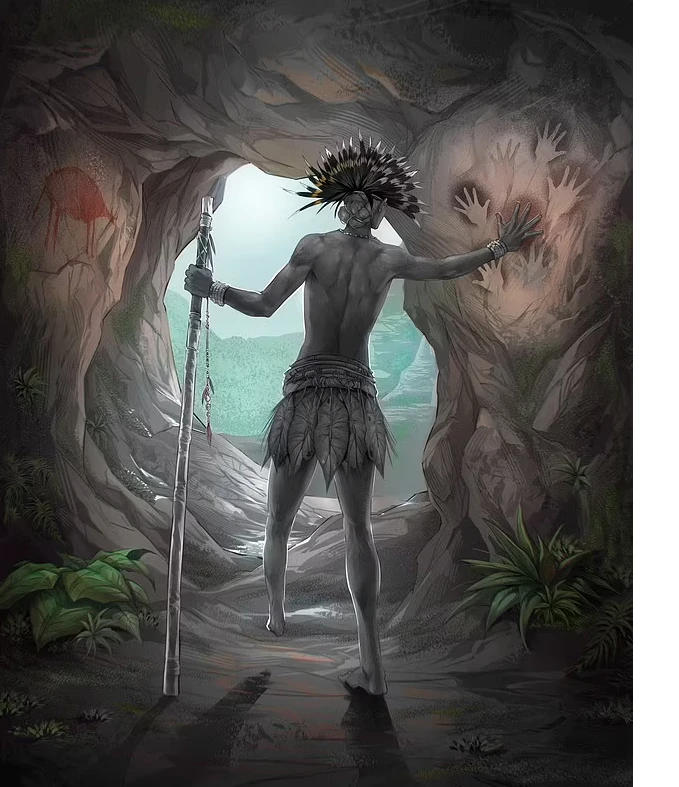

To put this date into context: 31,000 years ago the human species hadn’t reached North America yet. Written language had not yet appeared, and wouldn’t for another 25,000 years. The first metal tools wouldn’t appear for another ~20,000 years; this amputation was achieved with a blade of chiseled stone (probably obsidian). And the prehistoric Asians who carried out this procedure lived among monstrous Ice Age mammals, the ancestors of modern rhinos, hippos, and tigers. It was a very, very long time ago.

The Nature article has gotten tons of media coverage, but don’t overlook the five-minute video posted earlier this week by Griffith University, academic home of the paper’s authors. In addition to presenting scientific findings in reasonably accessible terms, the video illustrates the rugged terrain this long-lost patient had to navigate after recovering from the operation. It’s well worth watching.

Almost nothing was known about the prehistoric origins of amputation until this century. But the last two decades have produced an impressive body of evidence on multiple continents about Stone Age limb removal. All of these ancient cultures possessed the expertise not only to surgically amputate limbs but also to control blood loss and prevent infection well enough for patients to survive. And all seem to have developed these capacities independently—they’re too distant in location and time to have passed this knowledge to each other.

Here’s what the archaeological record shows about paleoamputation.

Europe, c. 4900 B.C.E.

Until last week, the oldest known example of medical amputation occurred near present-day Paris roughly 6,900 years ago. Documented in the journal Nature Precedings in 2007, this case involved a left above-elbow amputation that most likely was performed with a flint blade or axe. Like the researchers in Borneo, the French archaeologists used osteological clues to establish that a) the bone was deliberately cut, not traumatically severed or bitten off by a predator; and b) significant healing occurred, indicating the patient lived for many years after the amputation.

The authors hypothesize that the French patient required limb removal as a life-saving measure, after an injury left him with a gangrenous arm. “This is not an accidental amputation, but a real ‘medical’ choice,” they write. “Given that this patient survived, his caregivers must have had good knowledge of the needs and means to prevent blood flow through staunching, disinfection and [wound care]. . . . The unexpected attentions and technical competences in surgery given by this Neolithic group toward one of their elderly and disabled member suggests a considerable level of social, medical and even moral development.

The paper alludes to two other amputee skeletons of prehistoric Europe, one in Germany and the other in Czechoslovakia. Six years later, Bulgarian archaeologists published evidence of a below-elbow amputation dating to roughly 6,400 years ago. That paper appeared in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

Egypt, c. 2500 B.C.E.

It has long been known that ancient Egyptians developed prosthetic devices; the oldest examples date to roughly 900 BCE. But we’ve only recently seen evidence that they practiced medical amputation. It was found in 2010 by researchers from Al-Azhar University and the National Research Centre at Giza, and it suggests that surgical limb removal predated prosthetics by at least 1000 years. Published in the Journal of Applied Sciences Research, the study describes two cases of amputation, one below the knee and one below the elbow. The below-knee amputee was found in a burial ground for high-ranking members of society, while the upper-limb amputee was interred in a working-class cemetery. “The pattern of healing in both individuals, from two different social classes, suggests that medical care was equally [available] to them,” the authors write.

The same year, a joint U.S-Belgian investigation yielded similar evidence in four skeletons unearthed near Dayr-al-Barshā. However, a subsequent 2014 paper in Acta Orthopaedica expressed skepticism about the Egyptian findings, suggesting that skeletal evidence of limb removal is inconclusive at best. “There is no direct evidence for therapeutic amputations being part of surgery in ancient Egypt, especially concerning larger limbs,” this author argued. “Considering the level of Egyptian surgery in general . . . . the procedures described in the medical papyri are of a very simple nature. Not a single surgical incision has been found in any of the tens of thousands of mummies investigated from the Pharaonic period.”

India, c. 2000 B.C.E.

The evidence that ancient Indians practiced amputation comes from the Rig Veda, a 3,500-year-old collection of hymns and verses. In one famous episode, the warrior queen Viśpálā loses her right leg in combat, gets fitted with an iron prosthesis, and returns to the battlefield with more fury than ever. There’s no scientific evidence to support this story, unfortunately. The earliest documented cases of amputation in India date to about 600 BCE and refer primarily to punitive procedures: Criminals and war prisoners sometimes had their noses, ears, or fingers cut off. The famed Indian physician Sushrata, often referred to as the father of plastic surgery, made his name by reconstructing noses that had been severed in this fashion.

Peru, c. 200 AD

There’s both hard and soft evidence that ancient cultures of the Western Hemisphere practiced medical amputation. The hard evidence was first presented in 2000, when archaeologists unearthed three sets of remains from the Moche culture, each of which bore tell-tale signs of deliberate cutting and subsequent healing of the lower tibia. The soft evidence appears in ceramic figures from the same period, which routinely depict individuals who are missing an arm or a leg.

A more recent paper, published just last year, examines two similar Peruvian cases that date to somewhere between 1250 and 1500 AD (when the (Incas reigned), suggesting a continuity of surgical knowledge and limb care that endured for perhaps 1000 years.