By Tony Phillips

Limb loss and opioid drugs—sadly, those two things are commonly associated with one another. Virtually everyone who has lost a limb has had to consider when and how to move beyond limb loss without pain medications. For too many, however, the ongoing pain of life as an amputee and prosthesis user means routine dependence on medication.

Bob Lough is unaccustomed to asking for help. The 70-year-old Henderson, Nevada, resident served three tours in Vietnam with the U.S. Navy and following his service spent the rest of his working life in law enforcement. “I’m the guy people expect to solve problems,” he says. “It’s been hard learning to ask for help. But I tell everyone who asks about life after limb loss, you have to adjust to the person you are now.”

Lough lost his left leg below the knee in a motorcycle accident in April 2011. He is still passionate about riding. “I ride regularly,” he says. “You can’t live life in a bubble.” But his return to an active life was complicated by pain associated with his prosthesis. For four years following the amputation, he wore a prosthetic limb with a foot set at a fixed angle. “I had leg pain, hip pain, and back pain,” says Lough. “It’s all connected. If you have pain, you start walking differently, and that affects every joint all the way up the chain.”

Like many amputees whose use of a prosthetic limb causes frequent, even chronic pain, Lough sometimes depended on medication. “Ibuprofen is a great drug,” he says, “but when the pain is bad enough, you need something stronger.” For Lough and tens of thousands of other prosthesis users, something stronger means opioids. Prescriptions for Dilaudid, Norco, oxycodone, and other opioids are the typical course of pain management for physicians treating amputees with a range of pain problems, including residual limb pain, phantom limb pain, and hip, back, and shoulder pain.

“The problem with that,” says Lough, “is that besides interfering with your life, dependence on opiates can cause new and worse pain, and getting off the drugs is painful in itself. It’s just a whole series of bad things.”

Looking for a way to increase his mobility and confidence, and to address his difficulty using a traditional prosthetic foot, in 2016 Lough was fitted with a Freedom Innovations Kinnex foot. The Kinnex is advertised as microprocessor ankle/foot carbon fiber technology that provides low- to moderate-impact walkers with greater stability and ground compliance than typical prosthetic feet. In lay terms, the Kinnex includes a “smart ankle” that uses a microprocessor to anticipate and react to changing terrains and body positions, adjusting the foot angle to mimic organic function. The Kinnex flexes and extends to accommodate ramps, slopes, uneven terrain, sitting, standing, and squatting.

But aside from improved mobility, what Lough noticed about wearing the Kinnex foot was an immediate reduction in his pain. “You feel different wearing it,” he says. “You feel freer; you can do more. Some of it’s just psychological, probably. You believe you can do more, with fewer limitations. But if you believe it, it’s true. And so I noticed immediately that my gait was improved, that my body worked with the prosthetic more naturally, and with all that, the pain went away.”

Lough’s story is a common one. According to Freedom Innovations spokesperson Angie Ripullo, “It’s ironic that amputees have to pay more for such technology and also have to be higher functioning to qualify for them through their insurance carriers when, down the line, technology like the Kinnex foot saves money not only by reducing falls, but also, because the devices are more comfortable, they reduce prescription drug use and thereby reduce side effects associated with long-term use.”

The frustration Ripullo alludes to confronts prosthetists routinely. The best prosthetic technology can improve users’ functioning and reduce their pain and discomfort, but the best technology isn’t always a covered benefit. As a result, too many prosthesis users make do with what they can get.

Pat Bridges, a prosthetist at RGP Prosthetics in San Diego, says, “We see it quite often. A patient will come in with limited mobility, an uncomfortable fit, and chronic pain. Even though we can improve the patient’s mobility and minimize their pain, getting the appropriate products and components to address the issue can be difficult.”

“Patients with ill-fitting and contraindicated components have gait deviations,” says Bridges, “which can result in not wanting to wear the device, reduced activity, and pain. It can be a vicious cycle and part of the problem is the business model that prosthetists have to work with. If a prosthetist is unable to receive compensation for the appropriate number of test sockets, for building or providing components to adjust for changes in patient anatomy or functional levels, then the patient’s only option is to pay out of pocket, and for most people, the cost of the technology is quite prohibitive.”

Bridges adds, “What’s wrong with the system is that a given insurer is sometimes looking at a fiscal year consideration for patient costs. The fact is that the right prosthetic, the appropriate fit, and the appropriate components save money over time. Unfortunately, insurers aren’t necessarily looking at the long term. More often, they’re looking at reducing their costs in the short run for each individual patient.”

Linda Harlan, a 43-year-old above-knee amputee in Vancouver, Canada, considers herself a textbook example of patients who struggle with pain from conventional prosthetics. Following the loss of her leg in a car accident in 2009, she says, “I was mobile, but my prosthetic caused me so much pain that my altered gait caused soft tissue injury and actually bruised my femur. In eight years following my amputation, I had more than 50 check sockets built, and I went through 28 different finished sockets. One year I spent 320 hours in a prosthetist’s office. I even had two different prosthetists tell me they couldn’t work with me because they had been told how difficult I was to fit.”

Harlan’s experience with suction sockets included chronic, constant pain resulting from the misalignment of her femur and stress on the pelvis. “For almost four years,” she says, “I was totally addicted to pain medications. My doctor prescribed 200 Percocet every month, and I took every one of them.”

To reclaim a life free of pain and opioid addiction, Harlan resorted to raising funds by any means necessary to pay for an osseointegration procedure in Australia. “I took loans, maxed out my credit cards, scrimped and saved, and begged my surgeon for a deal,” she says. “He took 20 percent off the cost of the surgery, but in the end, I still spent six figures to get a procedure that I think literally saved my life. For two years since the osseointegration, I have been off all pain medications. I’m fully mobile, my bone is stronger, I’m more active, my muscles are equally developed on the sound side and the amputation side. I have a whole new life.”

Harlan was eventually reimbursed for the cost of her surgery by the British Columbia Ministry of Health, and since her experience in 2015, approximately 15 more patients in Canada have been compensated for approved osseointegration procedures overseas.

According to Fred Hernandez, North American representative for the Osseointegration Group of Australia (OGA), “We have now performed one hundred surgeries on North American amputees, and that number grows monthly.” The surgery was developed in Sweden as a two-step procedure, to improve quality of life for patients who cannot use a conventional socket prosthesis. Originally, a first surgery involved the insertion of a titanium screw into the residual bone, and in the second surgery, weeks later, an abutment was inserted into the fixture, leaving patients with a titanium shaft extending through the skin for direct attachment of their prosthetic limbs. In recent years, surgeons have begun performing the procedures in a single surgery.

Hernandez says, “The OGA team is the leading center in the world today. They have performed more procedures than any other center in the world and offer a single-stage procedure that has most patients [walking] in ten to 14 days.”

While the procedure remains controversial in North America, it is gaining acceptance in more countries every year. In fact, Canadian health authorities have announced their intention to approve osseointegration in the near future. Since that announcement, Canada’s provincial health services have stopped covering out-of-country procedures, meaning patients like Harlan are now waiting for regulations to catch up with their needs.

The frustration of those amputees is familiar to countless others whose pain and daily lives may be improved without reliance on powerful narcotics. Whether the impediment is a K-level rating, or an insurance carrier’s restrictions, or a regulatory agency’s reluctance to approve innovative technologies, the results are the same for too many amputees. Their lives include medication to combat chronic pain while an alternative solution, though available, remains inaccessible.

As amputee advocates and policymakers move forward in an age of rapid advancement, the right to access all available technologies still eludes people living with limb loss and limb difference. Giving all amputees the right to access the optimal solution to their unique cases can restore their functioning and, as Ripullo observes, “also be part of a solution to an opioid crisis that affects us all.”

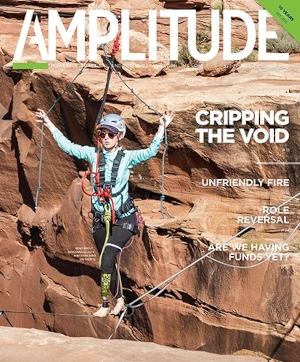

Image courtesy of Bob Lough.